Lessons in History

An interview with David Adelsheim, founder of Adelsheim Vineyard

Four decades have passed since the small and dedicated Willamette Valley winemaking community earned federal recognition for the region as an American Viticultural Area, or AVA. The designation was officially granted by the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms on December 1, 1983. Effective January 3, 1984, the Willamette Valley became the first AVA in Oregon and the 55th AVA in the country.

Today we survey a thriving scene where over 700 wineries ply their trade; reservations are often required at tasting rooms and Oregon wines are widely celebrated for their quality. It’s hard to imagine what the nascent Willamette Valley wine culture was like in the early ‘80s.

If you’ve ever wondered why the designated Willamette Valley appellation covers the ground it does, why it contains so many nested AVAs, or what it was like when the system was in its infancy, we’ve got answers straight from the source. We spoke with David Adelsheim, the man who completed the government petition paperwork.

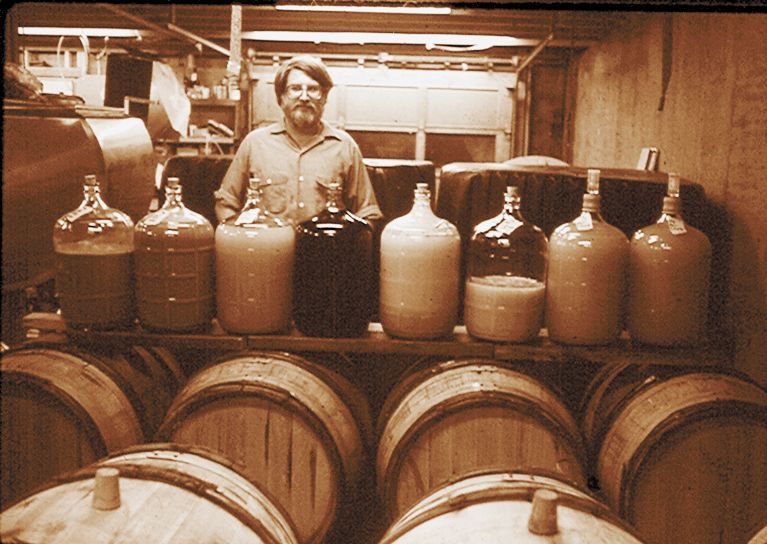

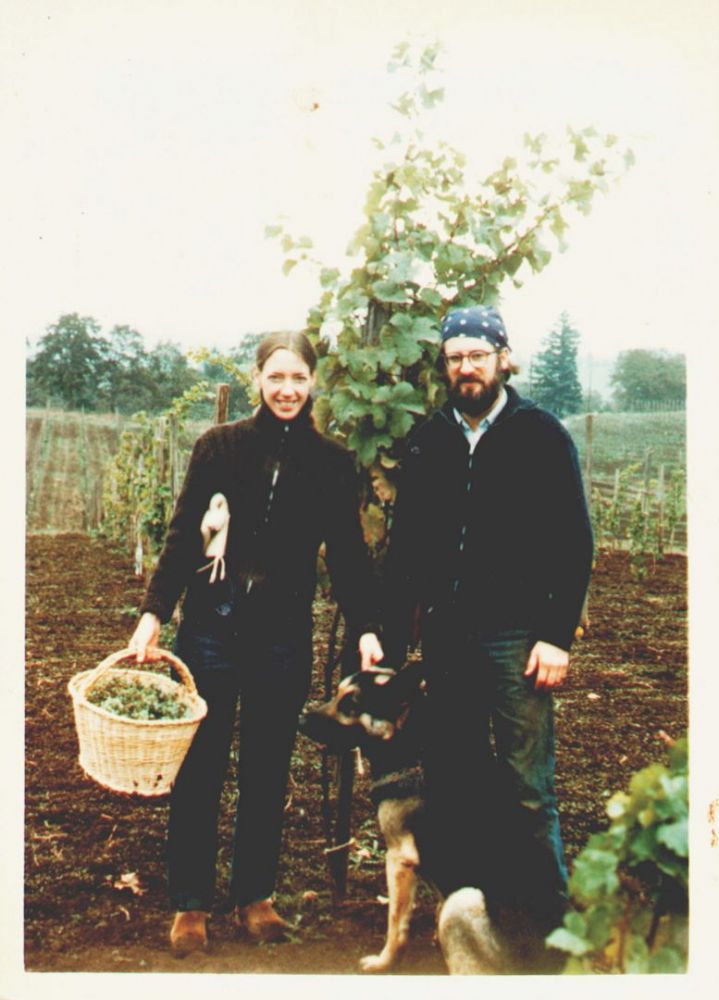

David Adelsheim founded Adelsheim Vineyard in the Chehalem Mountains with his wife Ginny in 1971, making their first wines in 1978. He’s worn all the hats: vineyard manager, winemaker, sales, marketing, accounting and fix-it guy. It should come as no surprise that his peers honored Adelsheim with a Lifetime Achievement Award during the 2012 Oregon Wine Industry Awards.

Adelsheim explains that the American Viticultural Area system was set up in 1979, in response to European challenges to the “wild west approach to wine labeling in the U.S.” One aspect of the newly launched government system required an AVA designation on wine labels in order to use the term “estate bottled.” According to Adelsheim, this new requirement proved a central motivation for Willamette Valley vintners.

Here’s our conversation with Adelsheim, edited for length and clarity, about his recollection of the AVA application process.

Why did the Willamette Valley wine community pursue AVA designation?

It dawned on the Oregon Winegrowers Association that a number of their members would no longer be able to use “estate bottled” on their labels once the new regulations went into effect. So, they frantically began trying to figure out how to get an AVA approved. Or multiple AVAs, since the organization had more than just the Willamette Valley growers to be concerned about.

How were the Willamette Valley AVA boundaries determined?

Our goal was to make the designated area as big as possible so that anybody growing in what we thought of as the Willamette Valley, i.e. the watershed of the Willamette River, would be included.

The process entails several things. According to the regulation, which hasn’t changed much since 1979, you must include a suggested name, one tied to the history of the place. Also required is information about the climate and geography of the place– it’s important to distinguish it from surrounding areas. The application must also include USGS maps with the proposed boundaries drawn onto the maps. Lastly, those boundaries also need to be described in words.

I proposed the largest area I thought we could have as the Willamette Valley. The boundary more or less ended where the national forests started in the mountains around the Valley. Because nothing is uniform, there were some places where we ended up merely drawing straight lines. The line we were using was basically the thousand-foot elevation line around the Willamette Valley. But sometimes the mountains weren’t that high. So, we needed to just draw a straight line and say “this is the end.”

There were a couple of questionable areas that we weren’t sure how to handle. One was in the south where the distinction between the Willamette Valley and some of the other nearby watersheds was hard to define. The other was the area just across the Columbia River from the Willamette Valley, where grapes also grow in basically the same climate. I wondered if either needed to be included. However, the government ignored both those questions and approved it as written.

Years later, King Estate Winery asked that the Siuslaw Valley– where their vineyard and a couple of others are located, be included within the AVA boundary. The requested addition was quite small and the climate was, in fact, identical, so it made sense to add it. Otherwise, the Willamette Valley AVA has basically remained as originally approved 40 years ago.

When and why were the nested AVAs established?

At the turn of this century, around 2000, many wineries in the area between Portland, Salem and McMinnville expressed interest being able to identify more specifically the places, where their grapes were grown, on their wine labels. In 2002, petitions for six new AVAs, all to be nested within the Willamette Valley AVA, were sent off to be considered for approval. These were all approved between 2004 and 2006. Since then, five additional designations have been granted. However, that hasn’t affected the Willamette Valley AVA, merely adding to its complexity.

What characterizes the Willamette Valley AVA and the Willamette Valley wine community today?

The focus on a single variety– Pinot Noir– was clearly extremely important to the success of the Willamette Valley. In the beginning, it was, at most, 40 percent of the total plantings, now it’s grown to 70 percent of what’s planted.

For another project, I’ve been researching a lot of local wineries. They share this common theme of falling in love with the process of making wine in the North Willamette Valley. This was my story in 1971. And, for virtually everybody, it wasn’t that they had a ton of money and they wanted to create an ego project. Merely that they loved the idea of wine and crafting this incredible product themselves. The growth has been organic, with a lot of high spots along the way. Many people played very different roles and nearly all agreed to be collaborative, in essence, helping raise the tide for the whole industry.

This collaboration– helping each other in the vineyard and the winery, tasting each other’s wines, critiquing them– all forced improvement and a focus on excellent winemaking and grape growing. People were, in some ways, competing against each other to be recognized for crafting great wine. Today we can look back and see that no single winery was “the” great winery. Instead, many people have had that place in the sun and handing it off to those following them. Each has contributed to building Oregon’s reputation.

What do you want to see for the future of the Willamette Valley?

I would like stricter grape variety origins and standards for wineries that use the Willamette Valley AVA on their labels. Those requirements could be helpful in protecting our reputation.

Government regulations describe the place and are valuable for informing customers where a winery’s grapes come from. But AVAs don’t speak to wine. In fact, the word wine isn’t in the federal regulation at all. It’s all about the place and being able to tell people where your grapes come from. However, what consumers want to know is: what are the wines supposed to be like when they come from this place that you put on your label? A wine label doesn’t answer that question so we need to help with that.

Another issue facing the Willamette Valley is one that comes with success. Now that we are known around the world as a fine-wine-producing region, how do we manage those who might take advantage of our hard-earned reputation for their own personal gain? Those too selfish to participate in raising the bar for everybody?

We need winery owners who can say “the Willamette Valley makes the best wines in the world.” They need to state publicly we make the best wines in the world. If the winery is actually owned by somebody in California, France, Italy, Australia or elsewhere, and they own another winery in this other place, they cannot say that.

Back in 1987, we encouraged the Drouhins to buy land and begin making wine in the Willamette Valley. I think it was one of steps that helped raise the bar and they have contributed to that. But how many French winery owners can we have in the Willamette Valley before we’re considered merely a colony of Burgundy? That said, today, most of the new wineries in the Willamette Valley are started by people already living here. Even established wineries being sold are often purchased by Oregonians.

But when Italian Chianti producer Marchesi Frescobaldi believes it’s in his best interest to own a winery in Willamette Valley… that gives me pause. Their recent purchase of Domaine Roy & fils means that suddenly a winery and vineyard land in the Willamette Valley is playing at a world scale. It’s incredible that the Willamette Valley’s reputation can somehow enhance that of Marchesi Frescobaldi…it’s crazy. That’s a big change from 1982 and ‘83.

What do you see for the future of wine in general?

Climate change is the biggest challenge confronting the entire world of wine. For the Willamette Valley and other places like Germany and Burgundy, thus far climate change has been largely positive. Recently, we’ve gotten to the point where it’s becoming more negative. How do we mitigate that? Who’s doing work to help us? That is the single biggest problem confronting fine wine in the world.

The entire world is in the same position. Some places– where it’s already warmer than it is in the Willamette Valley– have even more pressing problems than we do. But we all need help in two ways: figuring out how to lessen the problems of climate change and how to mitigate climate change itself. Those are two big questions that extend far beyond the Willamette Valley.