Walk on the Wild Side

Foraging expert leads tours of delicious discoveries

Just after eight on a warm August morning, two dozen people carefully examine the leaves on a thicket of heat-damaged wild roses just feet from the Springwater Corridor bike path in Southeast Portland.

“Imagine there are no flowers here, no rosehips here. How would you know this is a rose?” asks John Kallas of Wild Food Adventures, our foraging instructor. Someone proposes that wild roses have seven leaflets per stem, while domestic roses have five. “Not necessarily, they can have nine, seven, five … there’s going to be some variability here. And why is that?” After a brief dialogue, the answer is revealed: “Nature is not here for our convenience.”

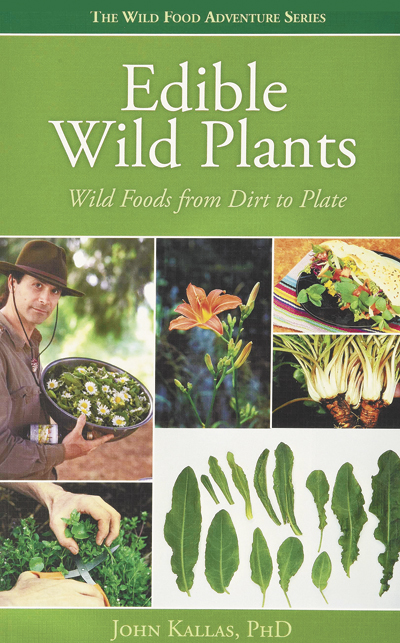

Within a few minutes of our three-hour class, it’s the second time we hear this adage — it won’t be our last. It’s Kallas’ way of reminding us how plants often defy categories, exhibit considerable variation and are not here to ease our jobs as plant identifiers — all reasons he wrote a plant identification book, “Edible Wild Plants.” The book he says he always “wanted but couldn’t find.”

We soon learn all roses can be identified by a pair of stipules, small flanges that flair out from the leaf’s stem just above the spot where it attaches to the branch. In the next few minutes, we also learn rosehips are not true fruits but resemble them in order to trick birds into eating them and scatter their seeds; roses and apples share same family; and how to select and process rosehips to eliminate the rock-hard seeds.

Wild rose chapter completed, we follow Kallas on a short stroll through the forested area near the spot where Johnson Creek, Johnson Creek Boulevard and the Springwater Corridor intersect to learn about our next foraging target: a butternut tree.

Career path

Kallas (pronounced KAY-lis) has been teaching about wild foods since 1978, launching Wild Food Adventures outdoor school in 1993. He also manages the Institute for the Study of Edible Wild Plants and Other Foragables, and for years has been cultivating and studying wild vegetables at his home garden. With a doctorate in nutrition, a master’s in education, and degrees in biology and zoology, he identifies as a trained botanist, as well as a nature photographer and writer.

By the time our three-hour class ends, we’ve identified at least 16 edible plants and learned details about their habitat, which parts of the plant are edible, and what time of year they are suitable for consumption. More importantly, we’ve learned how to be discerning about the food we gather and the information we glean from the many resources available to today’s forager.

We’ve also learned about nature’s vast capacity for variation, and how it’s not here for our convenience. For example, he began the tour on a patch of dry grass punctuated with cornflower-blue flowers on two-inch stems. Chicory. An edible plant that typically grows several feet high, here, it stubbornly grows on a public lawn, and the stress of being brutally and regularly mowed has persuaded it to flower in dwarfed condition so it can reproduce before it’s too late.

We also discover that the Springwater Corridor is a converted railway track, sprayed liberally with toxins for 80 years, and that gathering edibles from any railway embankment is ill-advised.

Why forage?

Kallas explains three compelling reasons to forage wild foods: “No. 1, it’s just fun. No. 2, it’s an activity that the whole family can do together. No. 3, the very best diets have great diversity.

“The Mediterranean diet should have been called the Mediterranean wild food diet because the original diet depended on Greek grannies going out and harvesting. They knew on average about 110 wild foods, and ate about eight species of vegetable matter for every one species we eat.”

Kallas started foraging in his youth. During a six-month backpacking trip around Europe during his college days in the 1970s, he talked to locals everywhere about their foraging practices. By the end of the trip, he was sourcing all his vegetables from the wild. He even returned to Michigan State University qualified to start teaching classes on the topic.

His first book, “Edible Wild Plants, published in 2010, soon will be followed by a second edition, headed to the printer shortly. Kallas offers multiple workshops throughout the spring, summer and early fall, with three classes on his September calendar focusing on wild forest fruits, neighborhood foraging and processing acorns. Every year, Kallas organizes a multi-day workshop on sea vegetables, shellfish and coastal wild edible plants in May, and another one on wild foods in June.

This time of year, fruits and nuts are the main quarry of the dedicated forager, with late summer and autumn adding elderberries, Saskatoon berries, chokecherries, Oregon grape, mountain ash, crab apples, hawthorn berries, black walnuts, acorns, native beaked hazelnuts and more. Some greens can be harvested in fall, including purslane, common mallow and sheep sorrel. During spring, the wealth of tender greens that burst forth can easily be harvested and sautéed, eaten raw, added to soups and omelets, pulverized into pesto or tossed on a pizza.

Climate change

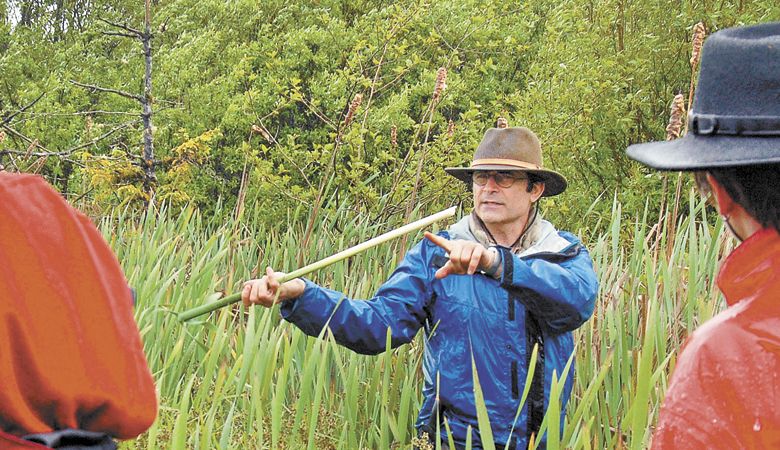

As a full-time wild foods expert, Kallas is uniquely attuned to the timing of when plants sprout, bloom, seed or die. “If plants are struggling, they want to go to fruit right away because their priority is to reproduce. They want to get the seed out there, but climate change is causing chaos. Some plants produce early and some produce late. I’ve been doing the same four-day rendezvous for 18 years. This year, the cattails were almost two weeks off. I really notice this because I have to set up these workshops nine months in advance, so I have to predict when things are going to be there in order to teach them.”

While Kallas’ workshop students may not go on to make wild foods a regular part of their diet, it’s unquestionably eye-opening to glimpse of the great variety and abundance of these forageable foods. Simply knowing another berry to nibble on in the woods, such as thimbleberries or Oregon grape, or a vibrant green to harvest in the spring like cat’s ear or wild sweet pea, can enrich a hike, camping trip or country ramble immeasurably, and potentially enrich one’s diet as well.

Hawthorn Sorbet

“This recipe can use any hawthorn berry. I used Crataegus crus-galli (Cockspur Hawthorn).” —John Kallas

4 cups hawthorn berries

½ cup cooking water

¼ cup lime juice

1 cup sugar

* zest from 2 limes, finely chopped

Place four cups berries in same amount of water. Cook until soft. Drain (saving water) and run berries through food mill or food processor to create purée. Set aside/ Dissolve sugar in ½ cup reserved water, plus lime juice and zest, stirring until mostly dissolved. Add purée. Blend all ingredients well. Finish in ice cream maker. Add sprig of fresh mint for garnish.