Triumph of Tempranillo

Abacela honors 25 years of leading an American-Spanish wine revolution

Story by Sophia McDonald

Photos by Andrea Johnson

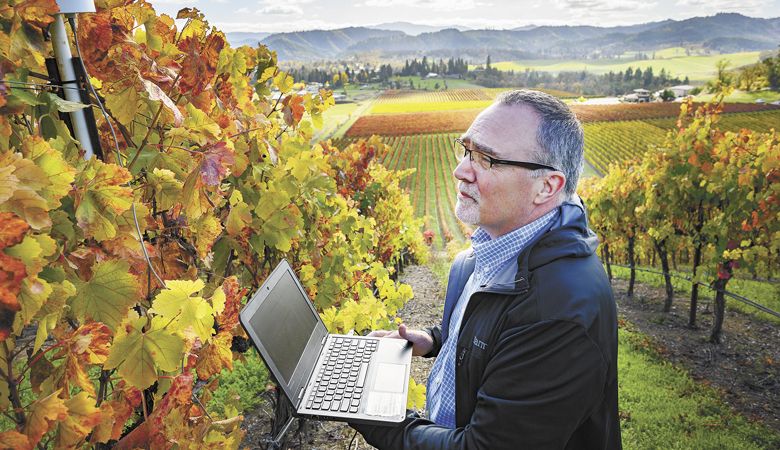

Twenty-five years ago, Dr. Earl Jones planted a dream in the Umpqua Valley. Jones, a dermatology researcher living in Alabama at the time, was deeply enamored with the wines of Spain. In 1990, ready to leave the medical field, he applied his skills and tenacity as a researcher to a new quest: finding the best place in the United States to grow Tempranillo.

That search ended in Southern Oregon. Jones has spent the last few decades proving the region had the ideal climate for the Spanish red wine grape. Besides spawning one of the state’s best-known wineries, Abacela, his work has led to a Tempranillo revolution establishing the variety as a standout from Roseburg to Ashland – and other parts of Oregon, to some extent.

As Abacela celebrates its 25th anniversary, Jones and others reflected on his legacy and the important role Tempranillo now plays in Southern Oregon’s wine story.

Jones grew up on a Kentucky farm that used Biodynamic and organic practices. He chose to attend medical school rather than toiling in the soil or becoming a basketball coach — that’s a whole nother story. After earning his MD at Tulane University, he completed his residency and started teaching at the University of California-San Francisco. He also worked at the University of Michigan and Emory University, where he met his wife, Hilda, a researcher in immunology.

Jones regularly traveled to Europe attending conferences and presenting papers. There were always fabulous dinners with local wines at these events. Despite the terrific options in France and Italy, “I began gravitating to the Spanish wines,” he said. He was already a fan; the owner of a shop he frequented in the Bay Area often recommended them. Over time, the Joneses’ appreciation only deepened for Spanish wine, food and culture.

At some point, Jones began to wonder why he couldn’t find good American-grown Tempranillo. From his time in California, he was well aware the state produced exceptional wines from a number of international grapes. But the little bit of Tempranillo grown was so low-quality it was typically used for bulk production.

“I got the feeling the problem was that in Spain, they grew in a different climate than exists in most parts of California,” he said. Places like Rioja, home to some of the best Tempranillo in the world, have a six-to-seven month growing season. In many California wine regions, the growing season is much longer.

By 1990, Jones felt disenchanted by the direction the American medical community was heading under HMOs. “I began to think, ‘What if I left medicine and spent some time trying to perfect Tempranillo in the U.S.?’ And so I did.”

Jones paid a visit to Spain with the express purpose of understanding the climate in the wine regions he treasured. His researcher’s mind turned to determining what part of the U.S. were the most similar. At the time, his son, Greg Jones, studying atmospheric sciences at the University of Virginia, would visit the library and copy loads of airport climate data on a dot matrix printer. Greg — now the director of the Evenstad Center for Wine Education at Linfield University — would then send a packet of papers to his dad, who would open it with the glee of a kid on Christmas morning and begin combing through the pages.

“You want a climate that begins to cool down when the Tempranillo starts to ripen, like in Rioja,” he added. “You don’t want temperatures that are still hot when the Tempranillo starts to ripen. It takes the vim and vigor out of the wine.” He traveled to multiple promising states, including New Mexico, Washington and Idaho, to investigate further.

The perfect spot for Tempranillo, Jones had learned in Spain, were areas unlikely to frost late in the spring or too early in the autumn. The area around Roseburg seemed the safest place to start a vineyard — safest in that it seemed unlikely an untimely frost or severe winter freeze would kill the fledgling plants. In 1995, the Joneses bought a 463-acre property and planted 252 cuttings from a nursery in California. In 2001, a wine from their second vintage won a double-gold and “best of class” at the 2001 San Francisco International Wine Competition. The historic submission made it the first American Tempranillo to win big at an international competition, proving Jones’ theory correct.

After earning such validation, there was no need to proselytize about the potential for Tempranillo. “People could see that it was working well,” he said. He invited to the vineyard anyone who wanted to learn about his work. He shared cuttings to anyone who asked. In 2004, he started the Tempranillo Advocates, Producers and Amigos Society (TAPAS), the first national organization focused on the grape. Soon Tempranillo vines — and the great wines they yielded — could be found all over the region.

Nora Lancaster, director of Kriselle Cellars in White City, has lived in Southern Oregon more than 20 years. She’s watched numerous people in the Rogue Valley AVA pull up other vines to make room for Tempranillo. “This is a grape variety that does really well with our particular climate and terroir,” she explained. While it makes beautiful single-varietal wines, local producers are also taking a cue from their Spanish counterparts and using it in interesting blends. Kriselle Cellars offers a Tempranillo-Grenache wine, a combination common in Rioja.

Red Lily Vineyards in the Applegate Valley AVA makes a rosé called Lily Girl, combining estate-grown Tempranillo, Grenache and Graciano. Winemaker Rachael Martin has always been a fan of Southern Oregon Tempranillo, both for the taste and the community it has inspired. “I feel like Tempranillo is one of the signature red grapes for the Valley. It’s really fun to be part of something with a lot of forward momentum and camaraderie,” she said. “There’s a lot of collaboration between people growing Tempranillo down here. That’s the beauty of Southern Oregon, that collaborative nature.”

Tempranillo makers in the area hold regular tastings and other events. As people have become more knowledgeable about the vinification process and various styles that can be made, the quality of the wines is more closely matching the quality of the fruit. “Over the last six or seven years, you can definitely see a trend where the winemakers who didn’t have experience with Tempranillo have gained experience with it, and those who gained experience with it early on have gained traction,” said Ross Allen, owner and agricultural operations manager at 2Hawk Vineyard & Winery in Medford. “You’re seeing the Tempranillo quality levels really beginning to escalate.”

Despite all the amour for Tempranillo, don’t expect Southern Oregon to make it exclusive. Local producers have long insisted they wouldn’t establish a signature grape in the way the Willamette Valley has focused on Pinot Noir or Napa became world-renowned for its Cabernet Sauvignon. “The Rogue Valley has so many different microclimates, and so many opportunities to grow many different varieties and grow them well,” Martin said. “That’s a really interesting aspect of the Rogue Valley. I do think that Tempranillo is a really nice match for our growing climate. The quality of those wines has been very good.” But the same holds true for Syrah and other big reds, which can ripen with ease in typical years.

“I believe the thing that makes us appealing to wine consumers is our diversity,” Lancaster explained. “Don’t come to us for one grape; come to us for all these grapes. Having said that, I think we are becoming more and more known for Tempranillo. I think that’s a good spotlight for us to have.”

Allen agrees, “Tempranillo will be in the top three reds of the Rogue Valley, but there are other varieties like Malbec that are being done so well now that I don’t see that Tempranillo production would ever outpace Malbec or some of the others.”

What does the future hold for Southern Oregon Tempranillo? Over the next 25 years, Jones believes it will continue to become more popular and widely available. As people learn more about it, he also expects there will be space for it to be made in more styles. The range can go from young and fruit-forward — called “Crianza” in Spain — to bigger and bolder in the style of the great Gran Reserva wines.

“I think the future of Tempranillo is well beyond Southern Oregon,” added Jones. “There are 100 people now selling Tempranillo in their tasting rooms in Oregon. Probably a quarter of that is in the Willamette Valley.” The grape is being grown and vinified all over the state and is also seeing success in places such as Washington and Texas.

Nearly all those wineries have one dogged researcher with a vision and a shovel to thank. Because of his tireless work to put the variety on the map and the palates of U.S. consumers, America is finally producing world-class Tempranillo and will for generations to come.