COVER STORY: Destination: The Dalles

Story by Mark Stock | Photos by Andrea Johnson

Like a lizard scampering toward the sunny side of a rock, there I was, following some instinctive draw east, barreling down I-84 to what I was told was Oregon wine country’s new frontier: The Dalles.

As I meandered through the outskirts of Portland past the polished Gorge gateway of Hood River, I couldn’t help but want a bit of what Lewis and Clark were after when they reached the Columbia en route to the Pacific. That is to say, I wanted something original, something new, something with unlimited potential. With a wine glass as my witness, I found it in The Dalles.

New is only new in the context of old, and perhaps nowhere is that truer than in a town of 13,000 about two hours by car from Portland. The Dalles, a town built on brick, salmon, a rushing river and, for a spell, the promise of gold, offers many lures today. Gold and grain have been replaced by Google and tech establishments. The agricultural side has persisted throughout, in the form of cherries, peaches, and, as of not too long ago, winegrapes.

The long growing season and relatively warm climate of the Oregon town on the southernmost tip of the Columbia Valley AVA makes for a wine scene not unlike anything else in the state. And with construction and ballooning production rates happening at just about every area winery I visited, The Dalles and surrounding vineyards are bubbling like a volcano on the eve of an eruption.

From I-84, The Dalles is little more than a line of truck stop signs, a few abandoned docks, a church spire or two, and some neatly placed hilltop houses. The Dalles Dam, completed in 1957, manufactures a torrent of water like Celilo Falls did naturally before hydroelectricity. With the rush of water as backdrop, it’s easy to imagine The Dalles circa 1890, when the population was greater than Seattle, Spokane and Yakima combined. And in the midst of natives fishing for salmon from handmade platforms and Thomas Edison designing a motor for a mill that would one day house Keebler flour, a Zinfandel vine was planted, the viticultural stepping stone for the Columbia Gorge AVA as we know it. Generations later, both the Columbia Valley and Columbia Gorge AVAs would combine to encompass more than 11 million acres and attract the spotlight typically tilted toward the Willamette Valley.

Lonnie Wright tends the roughly 120-year-old Zinfandel vines on his 20-acre vineyard near Hood River. His property, an old cherry farm, rests right on the border of the two AVAs. Turned on to vines in the wake of Chateau St. Michelle’s purchase of a farm he worked on in eastern Washington, Wright speaks like someone who has witnessed a few vintages. He speaks with an encyclopedic sharpness, spot-on when it comes to years and vintages. Absorbing the methods of Wade Wolf and Clay Mackey, Wright gathered the necessary, albeit informal, education needed to manage roughly 200 acres worth of fruit today.

“You learn enough to be dangerous with 2,000 acres,” Wright said, referring to his first vineyard gig. He went on to work in irrigation in Libya before returning to the Gorge. More on-the-job training led him to start his own vineyard management company in the early ’80s. Wright drove his ’62 GMC pickup to Underwood Mountain Vineyards and struck a deal with his first customer. “I said, ‘I’ll prune for you for two weeks if I can have the prunings,’” Wright recalled. There was a handshake and a truck full of cuttings. Years later, Wright had 20 acres of his own, which to this day, end up in the hands of Peter Rosback, of Sineann Winery, before putting on The Pines 1852 label.

To clarify, 1852 refers to the year Wright’s farm was carved into the region, seven years before Oregon became a state. Wright estimates the old-vine Zin to have been planted sometime between 1890 and 1900. They were discovered within a cherry orchard, burly and poorly managed, at least before Wright revived them. These vines still produce complex fruit, enough for Wright and Rosback to create an old-vine designate wine. Wright cites the 1985 Oregon State Fair as the turning point for Columbia Gorge Zin, when a wine from a resident vineyard took bronze.

The gravity of living vines nearly as old as The Dalles itself cannot be overstated. Wright mentioned how a group of Italians visited the vineyard in the mid-1980s, hearing word of these “big ol’ red grapes,” as they called them. Apparently, before Wright took over the plot and enhanced the vineyard, the fruit was being turned into wine for the Catholic church in The Dalles. Since, it has gained a few neighbors in the form of Merlot and Syrah and a bonafide owner and careful overseer in Wright. His efforts over many years earned him a lifetime achievement award earlier this year from the Oregon Wine Board.

Up in the cherry-blanketed foothills above The Dalles rests Dry Hollow Vineyards. The house-like tasting room occupies the site of an old dairy farm and is run by third-generation Dalles native Bridget Nisley and her husband Eric, a Wasco County district attorney originally from Madras. The two joke about the “money pit” that is starting a winery, especially with a child in school, but they’re clearly proud of their space and resulting wines. Dry Hollow sells a good swath of its 15-acre Hi Valley Vineyard, its first customer being more-than-established Maryhill Winery in nearby Goldendale, Wash.

Presently, Dry Hollow produces 600 cases of wine annually with Rich Cushman, of Viento, as vintner. Eric Nisley believes that where cherries do well, so do winegrapes. And he’s spent plenty of time with each, as Dry Hollow wines are crafted from a shared space in Hood River, where cherries are harvested and processed in the spring and grapes are brought in and transformed into wine every autumn.

The surrounding landscape is like a watercolor painting, the many greens of ripe orchards and budding vines fading into grassy, oak-studded hillsides. Mount Hood peeks out from the west, overlooking the Cascades and the shield they provide against the persistent rain the Willamette Valley is so accustomed to. The Dalles is just 13,000 strong and only minutes away, but nearly all metropolitan signs are buried in the many folds of Dry Hollow Vineyards’ serene setting.

Back in The Dalles proper, a couple of fresh producers, Maison de Glace and Quenett, are housed in fabled old buildings.

Maison de Glace operates out of a century-old structure once used for fruit storage and ice production by owner Kelley Lee’s great-grandfather — he vended large blocks of ice to various stores throughout the city, making deliveries in his late 1940s Dodge. Quite fittingly, Maison De Glace translates to “house of ice.” Kelley’s husband, Aaron, who crafts the wine, was a railroad engineer before falling into the fermented arts. There are plans to expand, but Aaron is currently busy producing about 650 cases per year, ranging from an unorthodox ice wine-style Roussanne to an aromatic and alluring Syrah aged in Hungarian oak.

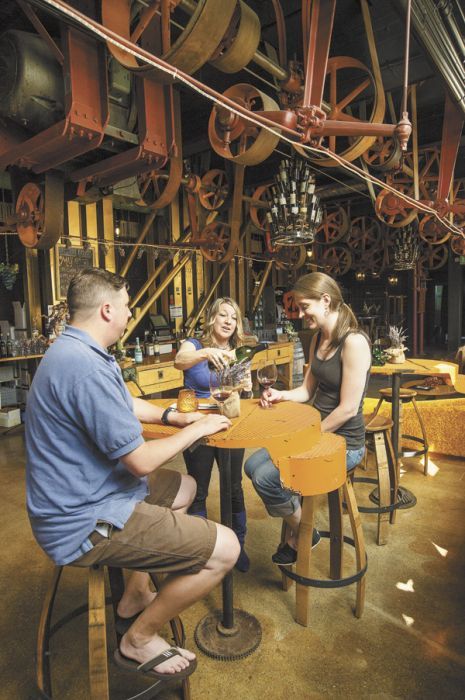

Quenett Winery produces its wines in the historic Sunshine Mill Artisan Plaza, a commanding gray pod of grain silos and warehouse space set right on the railroad line. Perhaps the most ambitious endeavor in the city, the only designated skyscraper in The Dalles has been carefully converted into a tasting room for Quenett — native word for steelhead — and a production space for Copa Di Vino, the mass-marketed portable cups of wine now available all over the U.S.

More intriguing, the structure has kept most of its original skeleton, from countless tubes and massive pulleys to a core motor designed by Thomas Edison. The mill was constructed in 1906 and milled wheat for several generations. During Sunshine Biscuit Company’s tenure, the resulting flour was used in Cheez-Its, the ubiquitous and irresistible construction-cone-orange crackers. Allegedly, Keebler later bought the mill and promptly sold it back to the city for cheap under the condition that it be used for something else entirely. Keebler — and its elves — seemed to have a grain monopoly to safeguard.

Exploring the Mill is as enjoyable as the wines — Zinfandel, Barbera, Sangiovese, Viognier, Chardonnay, to name a few. An engineer’s playground, with heavy industry looming in the form of levers, gears and 12 sky-high silos, the place demands exploration. An on-site hotel is planned, and while renewal is nothing new in The Dalles, the preservation-minded transition from old to new seems headquartered at the historic Sunshine Mill. Unsurprisingly, the Mill is owned and operated by a pair of Dalles natives, James and Molli Martin.

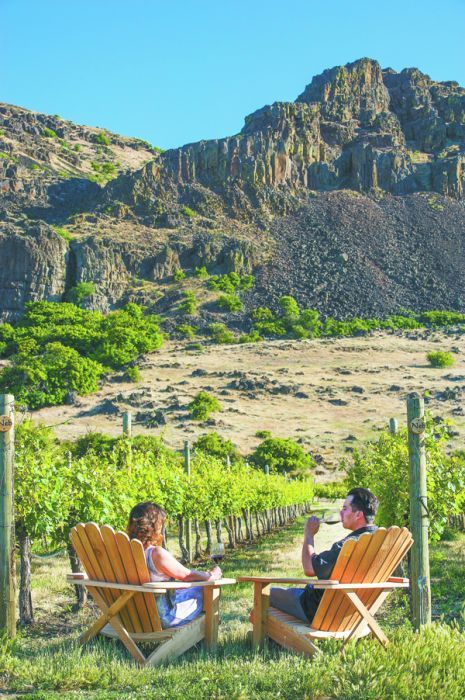

Bob Lorkowski of Cascade Cliffs Winery embodies the spirit of the Gorge wine scene. His Wishram, Wash., production facility and tasting room is a woodsy building that feels immediately like home. Set under towering, fortress-like basalt cliffs just a stone’s throw from the Columbia River, it’s quite obvious how Cascade Cliffs got its name. Here thrives the Northwest’s first commercial planting of Barbera (1990) and second ever Pacific Northwest planting of Nebbiolo (1988). Both are Piedmont varietals, the former being one of the most frequently planted grapes in Italy and the latter made famous by its inclusion in wines like Barolo and Barbaresco. “What’s that old phrase?” Lorkowski wonders aloud, finding it right away: “All the great grapes see the river.”

The former welder with a degree in finance moved to Seattle from back east to take a banking job years ago. From a blue-collar family, Lorkowski jokes that “you can’t take the moonshiner out of the kid.” Especially when your family is doing just that. Fascinated by fermentation from an earlier age, Lorkowski pounced on a chance to buy Petite Syrah from Cascade Cliffs when it was owned by Kenn Adcock. Lorkowski had always dreamed of living on a vineyard, but didn’t know the opportunity would arrive gift-wrapped. One day, as the story goes, Lorkowski asked to buy a little more fruit and Adcock responded with an offer of the whole estate.

“I saw what we’re doing well and did more of it,” Lorkowski frankly admits. He walks the vineyard daily and is both the owner and vintner for Cascade Cliffs. Sourcing Tempranillo from The Dalles and everything else from the Washington side, he makes about 5,000 cases per year. The old-vine Nebbiolo and Barbera are fantastic, while the newest Tempranillo from 2011 is surprisingly bright and accessible. “We joke about winemaker’s notes for our wines,” Lorkowski adds. “We say the average cellar time for most is about 15 minutes and that they have more body than Pam Anderson.”

A picturesque scene and warm company make Cascade Cliffs a worthy stop just over 10 miles from The Dalles. They do have a tasting room in The Dalles, but the remarkable geological character of the short trek — especially near the delightfully named Horsethief Butte — makes it worthwhile to see the source.

Neighboring winery Jacob Williams, presently working on an open-air tasting room expansion, is down the road. The windswept Zinfandel vineyard runs along a cherry orchard overlooking the river. Once based in Hood River, Jacob Williams — owned by Brad Gearhart and named after his two sons — still maintains close ties with Oregon, having once partnered with Dry Hollow. In fact, both owners are old friends — something I witnessed numerous times on this trip — and former college roommates.

Established in 2001, Jacob Williams produces 2,000 cases a year, sourcing some fruit from the south side of the river, taking Cab from Eagle Ranch in Echo, Ore. Sauvignon Blanc, Merlot, Syrah, Cab Sauv, Cab Franc, Zin, and a six-year Syrah Port round out an appealing list of offerings. John Haw, formerly of Maryhill and Sokol Blosser, mans the winemaking helm. Propped just above the Avery Recreation Area overlooking one of relatively few Columbia River islands, this is an ideal stop to reminisce about what the mighty Columbia looked like before the dams.

A few river bends to the east is Maryhill Winery, the stunning 3,000-square-foot facility known as much for their summer concert series as their wine. In its 12th year, Maryhill produces 27 wines from 19 varietals. The name comes from turn-of-the-20th century magnate Sam Hill and his wife, Mary, who tried their hand at a farming community on a nearby site in 1907.

While dry conditions pushed them out — in 1917 the Hills stopped farming as well as construction on their mansion now known as Maryhill Museum — but the vicinity ultimately proved ideal for estate grapes like Syrah and Sangiovese, among others. Ample production of 80,000 cases a year affords Maryhill a wide array of premium value wines, including a sunny-sipping rosé of Sangiovese and Grenache, the perfect accompaniment for one of the many summer concerts (Counting Crows, Willie Nelson…) held at the winery’s incredible amphitheater.

Returning to the Oregon side, The Dalles shines like Mount Hood in the distance, bubbling like its namesake dam, with history and potential and an emerging wine scene that demands to be experienced.

If You Go

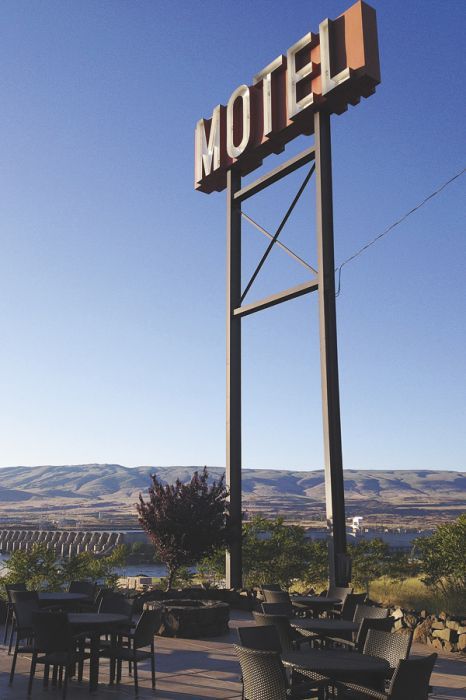

Formerly The Inn at The Dalles and Eddie’s Hotel, Celilo Inn (www.celiloinn.com) is a renovated 46-room hotel perched above the dam, overlooking the east end of town. The in features modern rooms, an inviting fire pit and courtyard, and the original neon “Motel” sign. Local wine is available by the bottle in the lobby and stunning photography on display throughout.

Fifteen miles outside of town, the 18-room and highly historic Balch Hotel (www.balchhotel.com) is a gorgeous blend of original craftsmanship and sharp retrofitting. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the hotel was constructed in 1907. Its style and architecture more than make up for its minimal modern amenities.

Situated on the west end, Cousins Country Inn (www.cousinscountryinn.com) offers a contemporary take on the Wild West, with ranch-style rooms and an in-house restaurant serving healthy portions. Set right off I-84, the complex has a truck-stop feel and always friendly staff.

In Town

Amid an urban renewal movement, The Dalles is bustling with activity. Hungry history buffs should visit Baldwin Saloon (www.baldwinsaloon.com), a former saddle shop built in 1876 with a remarkable 18-foot mahogany backbar, turn-of-the-century oil paintings, and a respectable local wine list.

Clocktower Ales (www.clocktowerales.com) offers a strong tap list and inhabits a stunning former courthouse constructed in 1883. The scene of the last public hanging in The Dalles, Clocktower fittingly serve Rogue’s Dead Guy Ale, among many other microbrews.

Klindt’s Booksellers (www.klindtsbooks.com), the seventh oldest bookstore in the U.S., is a fiercely independent and quaint establishment with amazing historical photos of the city. Look for the high water mark from the great flood of 1894 directly outside.

For more information on walking tours, museums, municipal murals and more, visit The Dalles Chamber of Commerce. As the Oregon Trail’s end, The Dalles offers much more to see and do.

Mark Stock, a Gonzaga grad, is a Portland-based freelance writer and photographer with a knack for all things Oregon. He currently works at Vista Hills Winery.