Remembering Richard

OWP Co-founder a memorable character, wordsmith and Oregon wine lover

Richard Hopkins, co-founder of the Oregon Wine Press, had a passion for words and wine, very specifically, Oregon wine.

He wrote in the March 1987 edition, “Our commitment to the growing success of the Oregon wine industry is deep and abiding... Our sincere belief in the brilliant future of Oregon wine makes this struggle to establish a marketing identity, our struggle; the growth of the industry, our mission; the fame of Oregon wine, our destiny and yours.”

On Nov. 26, 2015, Hopkins died from complications of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease; he was 84. At the time of his diagnosis, Elaine Cohen, Hopkin’s wife and co-founder of OWP, persuaded him to sell the publication to the News-Register in 2006, despite his desire to continue what he loved: writing.

Born and raised in Vancouver, Washington, he enlisted and served in the Air Force during the Korean War under SAC (Strategic Air Command). He learned to repair airplanes and did so until his exit in 1956. After his service, he attended Reed College in Portland, earning a Bachelor of Arts in English; Hopkins then earned a master’s in English from Washington University in St. Louis. Although he began the doctorate process, he never completed that final stage of his education.

Hopkins returned to Portland, where his professional life began. He worked for the city of Portland, and hired Elaine Cohen for a job in 1974 — it was a program under the Comprehensive Employment & Training Act (CETA). They were married in 1976.

His love of writing sparked a passionate career creating agency newsletters for organizations such as Portland OIC (Opportunities Industrialization Center) and the Men’s Resource Center, an early gay men’s group. He also started a newspaper for Project Return, an organization that assisted Vietnam veterans returning from war. He created a newsletter for the group and became friends with a number of veterans, including a returning soldier whose parents owned a berry farm in Boring, Oregon.

“A group of them got together and decided to start a fruit and berry winery while planting vines,” Cohen recalled.

Named Big Fir Winery, it was Hopkins’ first foot into the wine industry; the other was planted when his friend, Bill Miller from Big Fir, who was on the board of directors of the Oregon Winegrowers’ Association, tried to include Hopkins on the board. It didn’t happen, but Hopkins and Cohen made note of an opportunity in the OWA proposal drawn up by the Delkin Company, which managed OWA in the beginning.

“It said that there would be 5,000 additional associates that OWA could look forward to,” Cohen recalled, “and so our thinking was: If you have all these associates, you should provide them with something.”

And so the North Willamette chapter of OWA asked Hopkins and Cohen to run the associate program, which quickly evolved into a newsletter, the Oregon Wine Calendar, first published in 1984 — after a few name trials, Oregon Wine Press became the official and final moniker.

Cohen noted, “Nobody knew what was happening at any of the wineries; and, at that time, the mainstream press was not covering the industry; they didn’t think it was worthwhile; they had no idea about wine.”

Hopkins was the editor and photographer, while Cohen, she says, “did everything else.” They gradually added additional mailings, and the newsletter grew from there. As the publication continued, people’s attitudes toward Oregon wine changed.

“We worked a lot of festivals,” Cohen remarked. “At events like Newport [Seafood & Wine Festival] and Astoria [Warrenton Crab, Seafood & Wine Festival], we represented OWA and gave away the paper. The first few years, people would come up to us and ask, ‘What is the difference between red and white?’

“Then, one year, a local farmer in overalls came up and asked, ‘Who is making Chardonnay? I want to taste some Oregon Chardonnay,’” Cohen giggled, “And I thought, ‘Oh my, the world is changing.’”

Among readers, Hopkins was known for his editorials; he enjoyed writing them, too.

“He liked to get people upset,” Cohen said, “We did get the director of tourism upset, so we had to go meet with her.”

Hopkins also pushed some buttons in hopes of making a difference. For example, he wrote a commentary on the spraying of sides of roads using herbicides.

“No. 1, it wasn’t good [for the environment], and No. 2, it looked ugly,” Cohen recalled. “Of course, the viticulturists supported [the editorial] as well.”

Regarding other content, besides the popular calendar of events, there wasn’t always big news to share, so Hopkins and Cohen had to focus stories on where to stay — like some of the first B&Bs — and where to eat — surprisingly, not an easy task.

“Portland did not really have a great food scene back then, and we had to find restaurants that supported Oregon wine,” Cohen said. “We would go to restaurants and talk to them about carrying Oregon wine or talk to them about winemaker’s dinners.”

Besides writing and words, Hopkins truly loved Oregon wine.

“He was there to promote the industry,” Cohen said. “He sort of fell in love with the whole thing.”

Hopkins was also loyal and honest.

“One of the things he always said was, ‘I don’t want to make more money than the winemaker,’” and, of course, we never did,” Cohen laughed.

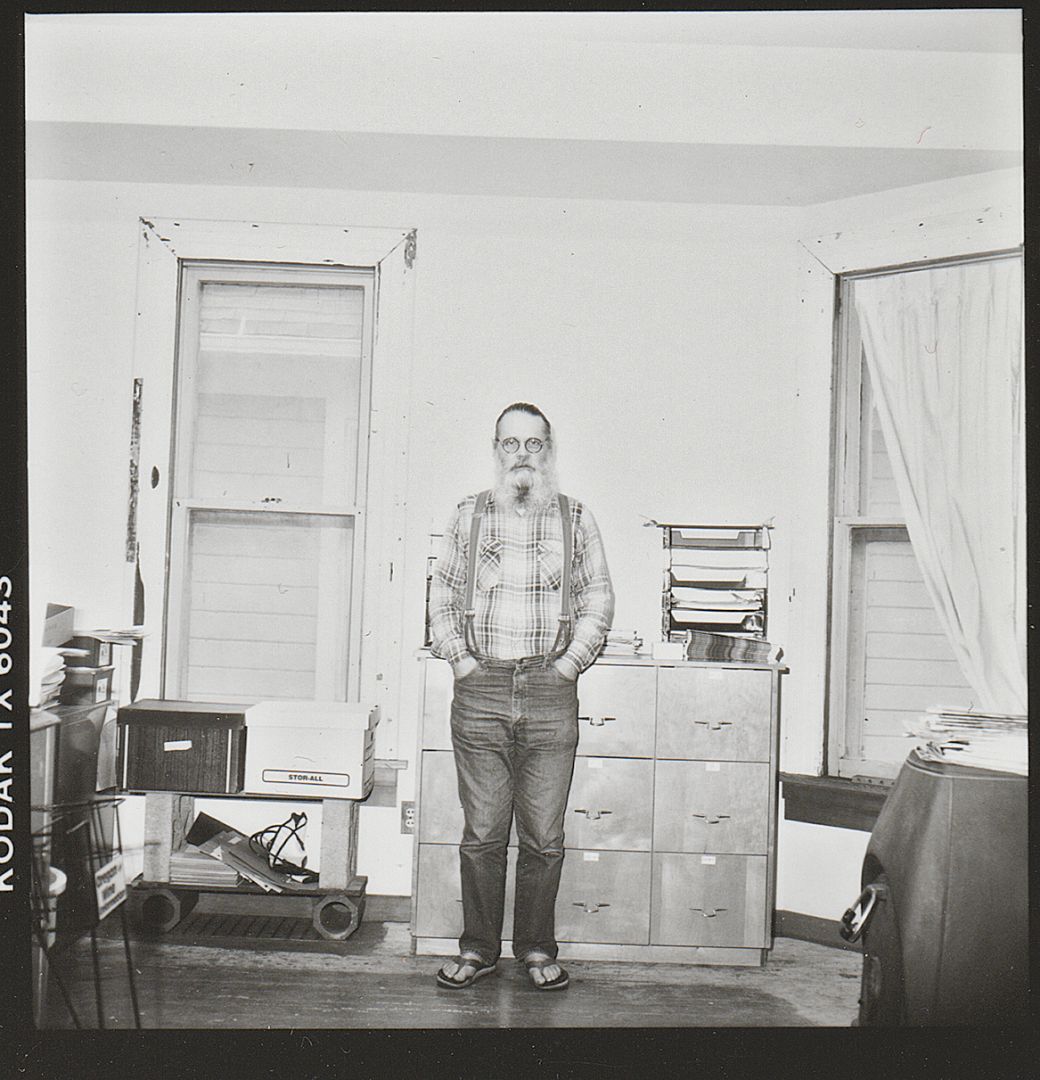

And he, always, dressed for the occasion.

“He would change his appearance based on his job at the time and current goals,” Cohen recalled. “When he worked for the Men’s Resource Center, he grew an Amish beard and long hair. When he went to Project Return, he wore jeans and Pendletons. When he worked for the city of Portland, it was three-piece suits and maybe a moustache.”

What did he wear for the 22 years as the editor of Oregon’s only wine publication?

“Birkenstocks and jeans, sometimes with suspenders, and, of course, a hat.”

Gore Vidal, Hopkins’ favorite writer, wrote, “Style is knowing who you are, what you want to say, and not giving a damn.”

That description captured Hopkins, a truly colorful character in the story of Oregon wine.

Hopkins is survived by his wife and five children (from two previous marriages), Daneal, Liné, Arice, Bryan and Belacane, as well as grandchildren, including Justine Larson, who worked for OWP when she was a teenager.

Cohen still lives in the once-grape-adorned house in Southeast Portland, where she enjoys her chickens and volunteering for the Native American Youth and Elders Center on Columbia Boulevard.