Re-wild at Heart

Bee conservation abuzz at Troon

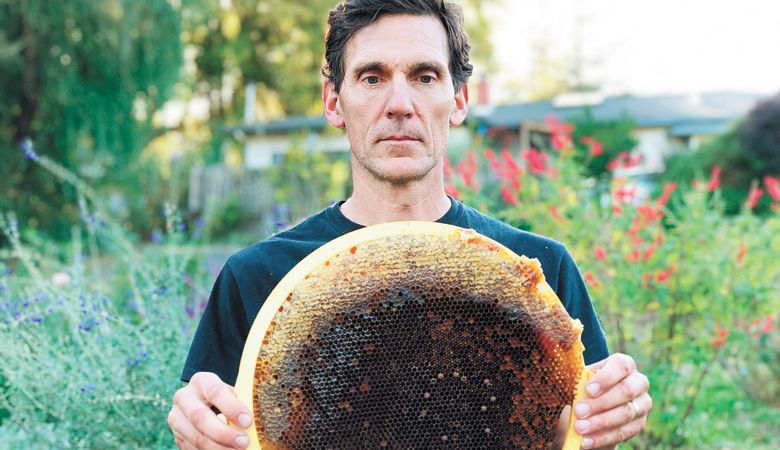

Honeybees carry a heavy load on their tiny wings. Considered a cornerstone species, “nearly 90% of the blossoming world depends on them for pollination,” says apiculturist Michael Thiele, founder and president of Apis Arborea.

He preserves and protects honeybees through a process he calls “re-wilding,” returning them to the wild. Thiele explains, “Honeybees are actually a forest-dwelling animal, as odd as that may sound to some people.”

Troon Vineyard in the Applegate Valley uses Thiele’s re-wilding to rehabilitate natural nesting habitats in the vineyards. “We are always looking for ways to increase biodiversity,” says Craig Camp, Troon’s general manager. “The more life we have on the farm, the better for everything. Also, as we now have several hundred cider apple trees, they can help with pollination.”

Although grapevines don’t require pollination, the surrounding plant species do, such as ground cover, wildflowers and fruit trees. “We know vines are not dependent on pollinators for pollination,” Thiele says, “so that can’t be the only reason for this. But the associated landscape, the associated ecosystem essential for soil health, for the health of the wider landscape, for the health of all agricultural species, we wish to foster that as a whole.”

In short, biodiversity thrives best with bees around.

Camp first learned about Thiele through Troon’s Biodynamic consultant Andrew Beedy, who met Thiele 13 years ago while working at Quivra Vineyards and Winery in California. “Michael’s approach to agriculture, where he puts the bee’s health at the center of all his work, fits well within the Biodynamic approach to agriculture,” Beedy explains.

A thoughtful, soft-spoken man, Thiele’s introduction to bees arrived with an unexpected swarm to his home in Northern California in the early 2000s. Desperate to find housing for the bees, he bristled at the traditional boxed hives available commercially. “I still remember to this day that it was a mismatch for me from the very beginning,” he admits. “That I couldn’t — I didn’t — understand how this design could ever be an appropriate nesting environment for this species of honeybees.”

Instead, Thiele researched alternative beehives and beekeeping methods, discovering a centuries-old European tradition carving hives from living trees. The design allows humans to remove the honeycomb with minimal impact to the bees.

Through trial and effort, Thiele eventually developed his own log-hives that “bio-mimic” tree habitats. Fashioned from hollowed redwood timber, he fits them with weatherproof roofs and easily removable wooden bottoms for accessing the honeycombs without disturbing the bees.

In 2020, following Thiele’s recommendations, Troon installed three such hives. One hangs aside the winery’s new pollinator habitat, part of its Biodynamic education area; another is parallel to the vineyard’s pasture — used for the sheep and compost — and a third is suspended within a wooded area.

“Bee colonies need a good distance between hives, which reduces competition between them,” Beedy explains. “We wanted a minimum of 300 meters (984.25 feet) between the Troon hives.” All suspend in tree canopies at heights of 12 to 18 feet, facing southeast for maximum morning sunlight, and less intense afternoon heat.

“The idea is to encourage natural systems on our farm,” says Camp. “Environmentally, we believe re-wilded bees will prove to have stronger immune systems, free of the many diseases and pest problems that plague commercial beekeepers. The long-term goal is to rebuild wild bee populations, so they can perform their critical role in nature. That role is not simply to provide us with honey.”

Camp observes intangible rewards to re-wilding bees, too. “The sight and sounds of wild honeybee hives are both emotionally and intellectually inspiring,” he says. “Simply put, it makes you happy.”

Thiele adds, “They are such phenomenal and quite unusual beings. There’s nothing really linear about them. The moment you touch them, you leave that path of reason and pure rationality, and default categorizations of what life is.”

Unfortunately, colonies currently face many threats, including commercial beekeeping practices, pesticides and global warming. For example, the typical commercial Langstroth hive reflects the harsh geometry of its 1850s inception, designed during the industrial age. Fabricated from thin wooden slats with narrow spacing, stacked at ground level, these high-density, square hives offer little protection or support to bees. Instead, they often prove cramped, disease-prone, and vulnerable to harsh temperatures.

“It’s not unusual for beekeepers with their managed colonies to lose 40% or 50% of the colonies every year,” says Dr. Thomas D. Seeley, the Horace White Professor in Biology Professor Emeritus within the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior at Cornell University, and author of “The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honeybee in the Wild.” “That’s not what we’re seeing happening in the wild. Having the bees in the wild is a valuable genetic resource for us.”

Increasing climate change adds to the urgency for honeybee re-wilding. “Conditions on earth have shifted dramatically,” says Thiele. “Climate emergency conditions are such that we have to develop new stewardship paradigms.”

As a keystone species, bees remain the “canary in the coal mine,” a warning system for the surrounding ecosystem. “Honeybees provide 50% of crop pollination services,” says Seeley. “In other words, if humans want to have agriculture and food, our fate is tied into that one species.”

Ultimately, regenerative and Biodynamic agricultural programs, such as those at Troon Vineyard, may offer a way to develop new management standards. “I would say regenerative, or Biodynamic agriculture, is trying to do that, to comprehend and integrate complexities, and to apply a new knowledge of the interdependencies of life,” Thiele concludes. “I think we’re in this very exciting time, wherever you are, waking up to a richness of life that has been lost in the last 200 years.”