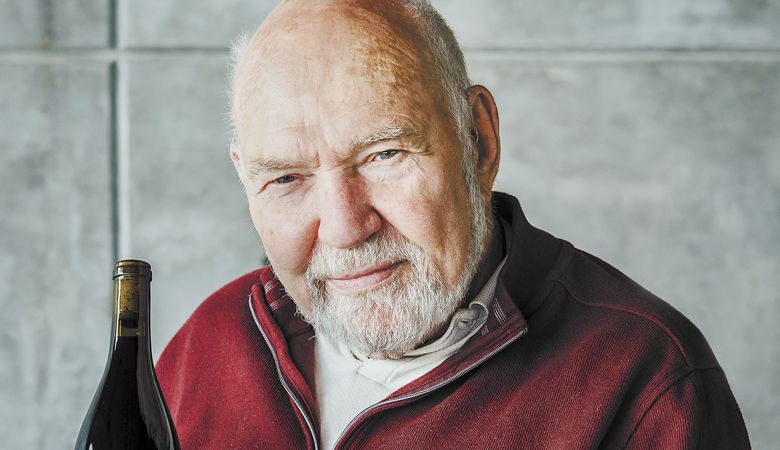

Q&A: Dick Erath

Oregon Pinot Pioneer

Former engineer Dick Erath was first inspired to pursue winemaking in 1965 following an early garage experiment. After completing coursework at University of California, Davis, in 1968, Erath moved his family to the Willamette Valley. An old logger’s cabin on 49 acres would serve as home – and impromptu winery — for many years. The following spring, he planted 23 varieties in the Dundee Hills, including Pinot Noir. By 1972, Erath had produced his first commercial wine of 216 cases at Knudsen Vineyard. Intrigued with French varieties, he soon became instrumental in importing French clones to Oregon. In 2006, he sold the winery and brand to Chateau Ste. Michelle. He now lives in Vancouver, Washington, with his wife, author C.J. David Erath. The Erath Family Foundation continues its contributions to the industry.

Before planting vines or making wine, how did you become interested in wine?

DE: It’s kind of interesting because my father’s father actually had a small cooperage in a little German village called Weinsberg. My dad could build a barrel from scratch at age 16 with hand tools, no power tools. He came to the United States in 1928, met my mother at Golden Gate Park at the bandstand there — my dad had a great voice, a great singer — and then I came along in 1935. There was no interest in wine, per se. We’d have wine around the house at Thanksgiving and during the holidays; my father was a Manhattan drinker, and my first wife and I would drink martinis.

When we moved to Walnut Creek, California, and bought our first house, there was a small cheese factory in Pleasanton, California, run by a Greek fellow. He would have all these wonderful cheeses —he’d have wheels stacked up in a tower for aging. He would pull a core out of the wheel for you to taste. We were really close to Livermore Valley, so we started going to a vineyard called Ruby Hill Vineyards run by an Italian fellow [Ernesto Ferraro], and he and I became pretty good friends. He had since sold the winery to the Christian Brothers but he still had inventory, and so he was selling off his wines. He had a black Malvosie and Zinfandel blend and he would charge $1.50 a gallon; it was dirt cheap. I would bring a gallon home and rebottle it into five bottles to spread it out. So that’s when we started drinking wine, along with the cheese.

How did you become interested in making wine?

DE: When I was going to college, I worked in the summer at a brewery, so I became familiar with fermentation sciences. One thing led to another, and I decided I would make some wine. I went to Ernesto, and I asked him if I could buy some grapes. He said, “Sure.” But he wasn’t supposed to do that because he was under contract with the Christian Brothers. But he sold me Semillon to make a barrel of wine, and he sold me two barrels. I’d gotten an old wine press from a fellow who sold farmers’ insurance; he’d collected it from a farmer who didn’t have enough money.

So I made my first barrel of wine in 1965. I took part of the garage and partitioned it off, and got an old Coca-Cola machine — the kind that you had to lift up and pull the bottles out vertically — and then took the refrigeration unit out and made a small air conditioner for the small space where I was fermenting the wine. Since I had worked at a brewery and was familiar with Berkeley Yeast Lab — that’s where the brewery would get yeast and have it tested, whatever they needed — and that became Scott Laboratories later on. A fellow by the name of Julius Fessler, the man who’d started Berkeley Yeast, had retired, but I would go to his house in the evenings — he was a real interesting fellow and a real scholar when it came to making wine — and he would tell me everything he knew, and, hopefully, a small fraction of it stuck with me. That got me started on the right track.

And then I heard about classes at Davis that were being conducted for people in the wine industry. Well, I wasn’t in the industry then, but they were being booked through the California Wine Institute; I told them I was going to be starting a winery soon and needed to take one of these classes. They said, “Fine.” They didn’t realize I was going to do it in Oregon, and so I started taking classes at Davis in 1967.

During a class with Vern Singleton, I asked about what was going on up in the Northwest — back then, everyone thought the only place you could grow grapes was in California. Vern said, “I had a couple guys who took this class last year” — it was David Lett and Chuck Coury. He gave me their contact information. Then Vern said, “But you don’t have to go very far; we’ve got Richard Sommer in the back of the room who has come down from Roseburg.” It was a great class because it was a class for winemakers, and you are learning as much from the guys in the class as from the professors.

When I introduced myself to Richard Sommer, he was very excited that I was interested in Oregon, so he gave me a bottle of Cabernet. As soon as I got home, I tasted it, and it tasted like whiskey barrels because he was getting freshly emptied barrels from Hood River Distillers and putting his wine in there without even rinsing them out. I could tell that there was really some nice fruit behind all of that.

About the same time — it was one of those things where it was all coming together — I was working in electronics at the time, and we had a fellow that we had hired from Tektronix in Beaverton at the time, and he worked for us for a couple years; well, the stock options didn’t suit him as well, so he went back to Tektronix, but he and I became friends. He called me up and asked if I wanted to come work for the company up in Beaverton. I said, “That sounds good to me” — about that time, I was ready to jump ship anyhow to grow grapes in Oregon.

I wanted to see Lett and Coury at the same time [as the interview], so I came up in the fall, October of ’67, to do the interview. Dave Lett wasn’t at home, but Coury was, so I went out to Forest Grove and sat at his house ’til the wee hours of the morning talking about grapes and everything. Then, on the way home, I stopped in Roseburg at Richard’s vineyard, and he was harvesting. He let me harvest some grapes; I think I got some Gewurztraminer and Riesling out of his vineyard. I packed the back of the car with grapes and drove down the highway, and smuggled them into California because back then you couldn’t do that.

I made the wine in my garage. The wines were really nice, so I took the offer from Tektronix and moved up all my winemaking equipment, my family, everything we owned, and started working for Tek. I was a couple years into that, when our office’s secretary said that I had received a call from a fellow by the name of Cal Knudsen. So I talked to him, and he was saying he was interested in growing grapes. So he drove down on a Saturday afternoon from Seattle, where he was living.

How [Cal] found out about me was through the state of Oregon’s economics commission. The head of the commission had a guy working for him by the name of Jack Potticary, and he created a flyer that said, “The Wine Grape in Oregon.” He interviewed me, Dave Lett, Chuck Coury and Richard Sommer; it was just the four of us, the only people growing grapes at that time. It had to have been 1969, I think, or ’70.

So that flyer came across Cal’s desk at his job, and he reached out to all four us, asking if we’d sell him some grapes; he wanted to make sparkling wine. I don’t know how the other guys replied, but I told Cal that I really wanted to make my own wine, and I thanked him for his interest. Then he called me, and he showed me the property in the Dundee Hills, where Page is now. So I went to work for Cal, quit my job at Tek, and I developed his vineyard, my vineyard and started my winery. I had my first vintage out of the basement of that house in 1972.

So that’s the short version of how I got into all of this. (Laughing).

Do you still live in Oregon wine country?

DE: We live in Vancouver now. When I sold the vineyard in 2017, I had sold the house, too, and we needed to find a new place to live. We looked around in Oregon; then a woman I knew introduced us to her brother, who was a real estate agent in Vancouver. So we came up and looked at houses. You get a lot more for your money here compared to Oregon. We ended up in Salmon Creek. We have five acres and a forest of cedar trees surrounds the whole house.

Are you currently involved in wine in any way?

DE: Yes, it turns out there is a small group of wineries here in Clark County and a couple in Cowlitz, the Southwest Washington Wineries Association. They remind me of Oregon 30 years ago: small family operations just trying to find their way. It’s difficult because I think they could grow Pinot here, but they really don’t want to because they feel like they will be the second or third wheel on the wagon, so they are looking to grow other grapes; they also buy fruit from the Yakima area making what I call “hot-weather wines.” Some probably won’t last, and some will. I’ve been able to sit in on their meetings and they’ll ask for my opinion on something, and I am not at a loss to give it.

Have you tasted any wines lately that have really surprised you?

DE: When I moved here, I accumulated a lot of wines over the years. I have a three-car garage here that’s full of wine, so I am going through those. I decided it’s time I better start drinking them instead of saving them, and I am surprised at how good some of the old Rieslings are. I’ve had some 40-year-old [Oregon and German] Rieslings that I thought, “Well, I’ll just open them up and see if they are any good — thinking they are not good anymore — and they are wonderful.

What advice would you give a new winery?

DE: I think they have to have a real clear vision on what they want to do. There’s no “just getting into it,” because everyone else is “getting into it.” It’s very competitive now; they really have to have a good marketing plan. It’s not hard to make wine — I mean, there are some Pinots that are difficult — but you have to be able to sell it. I think sales are a challenge, especially in the COVID times.

Is there anything you miss about growing grapes or making wine?

DE: I miss the whole process of it; I love growing grapes and making wine, but I still have a block down on Grand Island of Clone 95 of Pinot. This is a piece of leased ground that is very fertile soil and it is very isolated, so I was able to plant the vines on their own roots so there wouldn’t be any virus issue; the soils are very clean. [The vines] grow really well there. We provide budwood to nurseries for grafting of new plants; that was the purpose of planting there. I never thought that it would be a vineyard site in terms of making wine, but it turns out it makes pretty good wine there, too. And I think it’s because the clone is so strong. In 2012, we made a barrel of wine, and it was so overwhelmingly good. Right now, I am having my former vineyard manager who lives close by look after the vines; and he gets all the proceeds from the sales. Ismael “Mayo” Alba has seven kids, and we are trying to get them all through college. Two of them are through, except it got interrupted a little bit with COVID, but I really believe strongly in education.

Is the Erath Family Foundation still going strong?

DE: After I sold the winery to Ste. Michelle in 2006, I started the foundation in 2007. So far, we have been able to put a million dollars back into the industry. The significant [accomplishments] have been the classroom at Chemeketa in Salem; we finally got a van for ¡Salud!; and then we have been working closely with Oregon State when the smoke issue came out last year — we immediately funded them with money to do research on smoke taint.

It’s nice to be able to do these things. We are a small board — there’re only six of us — so we are not tied with protocol, so we can act really quickly. Right now, we are working very closely with Laurent Deluc at OSU and his genotyping of grape vines and looking at mildew resistance. He thinks we can develop a clone of Pinot Noir that would not be susceptible to mildew that would save the industry millions of dollars, and it turns out, the work he’s done has gotten the attention of the USDA, and they are jumping on the bandwagon and coming up with a lot more money than we did. So that’s sort of gratifying that we were able to kick-start something like that.

What would you like to be most remembered for?

DE: That I tried to make a contribution to the industry. I’ve always felt I was fairly lucky; I mean, I was in a situation where I came to an area and started an industry where there wasn’t one before. How many people can say that? … We had an opportunity to create a new viticultural area in the world. It’s very satisfying, and I hope I could be remembered as being a part of that.