Pioneering the Willamette Valley

A vision of the past with all eyes on the future

The roots of the Oregon wine industry run deep; vinifera and berry wines were being produced long before the Prohibition era. In fact, the land in Forest Grove where David Hill Winery is now located used to be known as David’s Hill, then Wine Hill. The Reuter family, who built the farmhouse where David Hill stands, established a reputation by the 1880s for their Klevner wine (an Alsatian term describing either Pinot Blanc or Chardonnay), for which they won a gold medal at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904. And in Southern Oregon, Peter Britt was growing wine grapes in the 1850s on what’s known now as Valley View Winery.

Prohibition changed everything. Many of the region’s grapevines were ripped out and replanted with legal crops. Some growers were able to preserve their vines, selling their fruit as unfermented juice. The land was dry for years following Prohibition, until Richard Sommer sparked Oregon’s modern era of winegrowing in 1961 by planting wine grapes at his HillCrest Vineyard in the Umpqua Valley, Oregon’s oldest estate winery.

In the mid-1960s, a fresh wave of trailblazers emerged. First David and Diana Lett of The Eyrie Vineyards, and Charles and Shirley Coury of Charles Coury Vineyards. And like a rolling snowball gathering snow and building momentum, the Willamette Valley wine community quickly grew.

A group of brave visionaries found one another and began working together, sharing their successes and failures, building something in which they mutually believed. They were united in their efforts to accomplish what critics were calling impossible and prove the skeptics wrong. Some thought they were crazy; others called them radical. Though not the first, they were avant-garde, paving the way for the modern Oregon wine scene and putting Oregon on the world wine map. Without their forward-thinking, their dedication, the Oregon wine industry would not be what it is today, with 18 approved AVAs and more than 700 wineries producing wine from 70-plus grape varieties.

Though the following is not an exhaustive list, here are a few of their stories from the Willamette Valley before 1980.

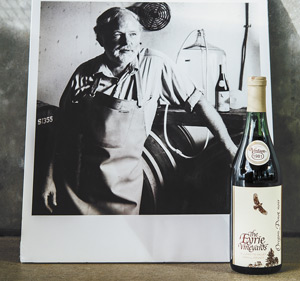

David and Diana Lett

The Eyrie Vineyards

According to Diana Lett, her husband, David, liked to say that he was hit by two cosmic bricks in his early years. The first enlightening occurred in 1962, when, on a whim, he visited Napa Valley on his way home to Utah. He met Souverain’s legendary winemaker, Lee Stewart, and spent time rolling barrels in the winery; he decided winegrowing, rather than medicine, would be a fine way to spend his life. Several months later, he enrolled at UC Davis to obtain his second bachelor’s degree in viticulture and enology. The second illumination took place in his winetasting classes at Davis, where he had the opportunity to experience wines from the great vintages of Burgundy. He fell in love with Pinot Noir: its haunting flavors, its history, its finicky challenges in the vineyard and winery.

After graduation, extensive research and travel in northern Europe convinced him that the Willamette Valley, with its unique climate and long, cool growing season, might possibly make a successful home for Pinot Noir outside Burgundy. Although Sommer was growing and making Pinot Noir — the first in the state — in the Umpqua Valley, no one was growing vinifera in the Willamette Valley. In early 1965, David arrived in Oregon with “3,000 cuttings and a theory,” and planted the first Pinot Noir and related varieties in the Willamette Valley.

Charles Coury, David’s classmate from Davis, also was focused on the possibilities for vinifera wines in the Willamette Valley. He and Shirley moved to Oregon later that year and purchased vineyard property near Forest Grove. Diana says, “It was good to have at least two other people in Oregon to talk about grapes with!”

Pinot Noir was always David’s driving force, but he was also interested in experimenting with other classic northern European varieties in Oregon, including Chardonnay, Pinot Meunier, Gamay Noir, Riesling, Muscat Ottonel and the first New World planting of Pinot Gris.

Ask Diana what the scene looked like in the ’60s and early ’70s, and she recalls, “There wasn’t much of a wine scene anywhere in the U.S., much less Oregon. There were some big hybrid-grape wineries in New York and a handful of wineries scattered in the Napa Valley, but only a few were making premium single-varietal wines. Almost no one had even heard of Pinot Noir.”

The food scene wasn’t any better, and it was definitely not glamorous to be a winemaker or chef. The Letts were just hoping they could make a living by developing a small group of aficionados around the country who would, ideally, buy all their wine upon release. Their first efforts weren’t very encouraging. According to Diana, “When we were ready to release our first vintage, made in 1970, we designed a beautiful little brochure announcing Willamette Valley Pinot Noir to the world, and mailed it out to 400 known wine consumers. We got exactly one response and realized that selling Pinot Noir — at $2.50 a bottle— might be even harder than growing it.”

Diana says she and David always had the feeling they were doing something important. Making a little history, at least. And if the industry grew, perhaps, eventually, their group efforts would help enliven the national culture. The wine and food scene had a long way to go, but it gradually improved, thanks to more international travel, and Julia Child and James Beard cooking on TV. Diana recalls having lunch with David one day in a Portland restaurant in the mid-’70s and thrilled when they saw someone else ordering wine with lunch.

The tradition of working together started early here, almost as soon as there were enough winegrowers to call themselves a group. What they lacked in funds they made up for in high ideals. From the outset, they realized they had a unique opportunity to mold an industry from scratch; they focused on doing it right. The Letts and others were also marketing visionaries, as most also recognized that, given the climate and the wine varieties chosen, the only way they would survive was by emphasizing quality over quantity. They worked together, establishing research, advocating farmland protection, sharing information and equipment, and drawing up the strictest labeling regulations in the country — among many other projects. This tradition of creativity and cooperation is unusual in most wine regions but has served Oregon well. When asked about what the future holds for the industry, Diana says, “Working together and individually to achieve quality is the legacy I hope will be treasured and enhanced by Oregon winemakers to come.”

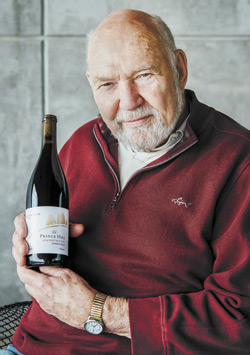

Dick Erath

Erath Winery

Ask Dick Erath about his aha wine moment, and he’ll tell you a love story. He recalls somewhere in the time frame of 1965 to 1966, he fell for Pinot Noir, specifically a 1955 Beaulieu Vineyards made by André Tchelistcheff. He was hooked.

In 1967, Erath, while attending school at UC Davis, fortuitously met Richard Sommer from Oregon’s HillCrest Vineyard. One of his professors told him how Charles Coury and David Lett had recently moved to Oregon to start vineyards. That October, he interviewed at Tektronix in Beaverton. While in Oregon, he met with Coury — Erath says they talked until 4 in the morning. After returning to California, Erath read Coury’s master’s thesis (published in 1964), which explored growing grapes in cooler climates. Instinct and research convinced him Pinot Noir in the Willamette Valley was a perfect match.

Erath accepted the job at Tektronix and moved to Oregon. He found a site in the Chehalem Valley and started planting in 1969 with starts he had rooted in Dundee in 1968. He admits, at the time, they were all on a steep learning curve. And the group thrived on collaboration.

Regarding the Willamette Valley as a major player in the world of wine, Erath says, “I never thought of failure. I also never thought it would become the giant that it is!” Although he sold the winery in 2006, he still makes a barrel of wine every year, as he’s done since 1965.

Ronald Vuylsteke and Marjorie Vuylsteke

Oak Knoll Winery

For Marjorie Vuylsteke, the idea of making wine began with her love of canning food for her growing family, six children in all. She says, “I was busy canning fruit and vegetables from the garden and the farm, and I thought, ‘I wonder about preserving wine?’” She looked for a recipe. No such luck. Little did she know, it was an involved process and not so simple. This did not stop her or her husband, Ronald Vuylsteke, who was working with Dick Erath at Tektronix at the time. He describes how they would spend their coffee breaks discussing winemaking.

Naming their brand, Oak Knoll, the Vuylstekes started with berry and fruit wines and eventually produced their first vinifera, a 1971 Zinfandel from a vineyard in The Dalles. They would make their first Pinot Noir in 1973, after Ronald became focused on the Burgundian grape. He recalls one particular high point of his winemaking career, when he entered his 1983 Pinot Noir in the Oregon State Fair and won Best of Show. He remembers, “One judge was André Tchelistcheff of Beaulieu Vineyards, who called me and told me ‘I’ve been searching for 50 years for a great Pinot Noir; your wine is near the top.’”

Another validating moment occurred with the Valley’s first French vintner. He recalls, “I got a call from the Burgundian legend Robert Drouhin. Robert, his wife, daughter Véronique and winemaker wanted to visit. I did a vertical tasting of my Pinot Noir from 1979 through 1983.” Robert’s indelible comment? “This is great; it is as if I were in Burgundy.”

Bill Fuller and Virginia Fuller

Tualatin Vineyard

Bill Fuller worked as a high school chemistry teacher in California when he discovered wine. He began doing lab analysis for an Italian winery on the side, and then went on to earn a master’s in food technology, with specialization in enology from UC Davis. With his chemistry background and formal wine education, he landed a winemaker job at Louis M. Martini Winery in California.

During Fuller’s time at Davis, he crossed paths with Charles Coury and David Lett. He says, “The idea of exploring a new region was appealing to me.” So, in 1971, he began exploring Oregon vineyard sites with Bill Malkmus, a San Francisco investment banker who would become his partner. The two purchased 65 acres northwest of Forest Grove; in 1973, began planting the Tualatin Vineyard. At the time, he was the first actively employed, professional winemaker from Napa to settle in Oregon.

Fuller recalls the early struggles selling wine, a time before people knew what Oregon wine was. “We were a ragtag, under-capitalized group. New vineyards, new wines and no money. It was quite a learning process.”

As it turned out, he was instrumental in blazing the trail into market acceptance, both inside and out of Oregon. The world took notice when Fuller’s 1980 Pinot Noir and 1981 Chardonnay won “Best of Show” in both red and white categories at the 1984 London International Wine Fair — a feat never achieved by any winemaker in the competition’s history. Then, in 1992, the 1989 Tualatin Estate Chardonnay was the first Oregon wine to land on Wine Spectator’s “Top 100” list.

Earning recognition for wine wasn’t enough for Fuller. In 1982, he worked with Bill Blosser to merge the Winegrowers’ Council of Oregon with the Oregon Winegrowers Association (OWA), on which he later served three terms as president. While working with the OWA, he met Willamette Valley Vineyards founder Jim Bernau, at the time a lobbyist for small business. Bernau has credited Fuller’s vision and early plantings at Tualatin Estate Vineyards for making the difference in his winery’s growth.

Bill Fuller and his first wife, Virginia, worked to establish the blue winery directional signs we see guiding us around wine country today. he says, “Virginia did the heavy lifting on that one.”

This year marks Fuller’s 60th year making wine. How’s that for commitment?

Dick and Nancy Ponzi

Ponzi Vineyards

In their quest for the perfect spot to settle down and make wine, Dick and Nancy Ponzi stumbled upon a newspaper clipping about Richard Sommer growing wine grapes in Southern Oregon. After visiting Sommer and discovering his Pinot Noir, they began exploring Oregon and cooler climate regions. They chose the Willamette Valley; the year was 1969. After purchasing a 20-acre parcel in Beaverton, they ordered their Pinot cuttings from California and became acquainted with three other families sharing similar plans and dreams for growing Pinot in the Valley. Their first vintage was 1974.

The Ponzis were instrumental in establishing many of the laws and guidelines about sustainability and organic farming; for example, Nancy lobbied in 1973 to pass the first legal definition of organic with Oregon Tilth, along with the nation’s earliest ingredient labeling laws. She has also worked to provide health care for vineyard workers, helping create the highly successful ¡Salud! organization, which provides medical services to vineyard worker and their families. In addition to wine, they also helped establish Oregon’s other major beverage industry: beer. In 1984, they started Bridgeport, the state’s first microbrewery.

Humbly, Nancy recognizes the family was far from alone in creating the foundation on which the Oregon wine industry stands today, “We deeply understand that establishing and maintaining the winery would have been impossible without the contributing talents of individuals, market conditions and the overall environment.”

On their vision for the future of the land and the wine industry in general, she says, “Our responsibility is to make it better. It may sound corny, but this is what we teach our children and grandchildren.”

Pat and Joe Campbell

Elk Cove Vineyards

Oregon natives Pat and Joe Campbell loved wine. They spent many weekends tasting at wineries near Stanford, where Joe was pursuing a medical degree. Tasting was free and they enjoyed afternoon picnics with wine as developed their palates during the time Joe was an intern in San Francisco. A dinner celebration in 1972 at La Bourgogne Restaurant where they enjoyed a bottle of 1969 Le Musigny clinched their choice of the Pinot Noir grape for their future quest.

The Campbells returned to Oregon. In 1973, knowing they wanted to farm, they purchased a hillside property of 112 acres in Yamhill County near Gaston. They quickly decided they would grow grapes.

With Pat’s farming background and superior palate and Joe’s education in biology and chemistry, they felt confident they could grow grapes and make wine. They immersed themselves in books, took short courses in winegrowing at UC Davis and visited wineries in France. Local winegrowers like the Courys encouraged them and sold them own-rooted Chardonnay and Pinot Noir vines, enough to plant five acres of each in the spring and early summer of 1974. They studied weather and believed those varieties would do well in our climate. The couple produced their first wine in 1977.

Asking Joe about his decision to grow grapes, he says with exuberance, “We have not been disappointed!” He elaborates, “At the time, we had no idea how successful Oregon winegrowing would become, and I don’t believe anyone else did either.”

Today, they’re proud to be family-owned with a future not directed by a large corporation, remaining hopeful the tradition of small, family-owned and -directed winegrowing continues. They’re fortunate their son, Adam, decided to become Elk Cove’s second-generation winegrower, explaining that is the legacy of which they are most proud.

Bill Blosser and Susan Sokol Blosser

Sokol Blosser

When Bill and Susan Sokol Blosser first decided they wanted to make wine, they were looking in the Philo area of California because they wanted to grow Pinot Noir and believed the climate ideal. By chance, an Oregon realtor referred them to Dick Erath, who had recently started planting Pinot Noir on Ribbon Ridge. Dick gave them a copy of Coury’s master’s thesis on climate — which had seemingly become the Oregon wine bible — revealing how the Willamette Valley was ideal for cultivating Pinot Noir. At that moment, they decided to remain in Oregon.

The couple purchased an abandoned prune orchard and began planting grapes. When they started, they focused on Pinot Noir, but hedged their bets, as did everyone else, with other cool-climate grapes such as white Riesling, Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc, Müller-Thurgau and Pinot Gris.

When asked if he could have anticipated what the Willamette Valley wine industry would become and the legacy he’d leave for future generations of winemakers, Bill humbly replied, “We had no idea what would happen; we were too focused on day-to-day issues to indulge in huge flights of fancy.”

He’s very satisfied by what Oregon wine has become and how it is now regarded as one of the premier winegrowing regions of the world.

David Adelsheim and Ginny Adelsheim

Adelsheim Vineyard

David and Ginny Adelsheim were living in Portland but wanted to move to the country. David says they first ran into Dick Erath; then met Bill Blosser. “The rest is history,” David recalls. “Had we not met them in April of 1971, we’d likely have had a very different life.”

In the beginning, Adelsheim, like most everyone else, planted the great wine varieties of northern Europe: Riesling, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. In subsequent years, they tried small amounts of Sauvignon Blanc, Merlot, Pinot Blanc, Gamay Noir, Auxerrois, Syrah and large amounts of Pinot Gris, almost all of which have now been removed as the winery has refocused on solely Chardonnay and Pinot Noir.

When asked if he could have anticipated what the Willamette Valley wine industry would become and the legacy he’d leave for future generations of winemakers, he says, “We could not have possibly known what would take place over the ensuing 47 years. It was not just the Oregon wine industry that changed; the entire idea of American luxury wine was created in that time.”

As the industry continues evolving, David hopes we can focus on defining the neighborhoods with common wine attributes and that we can determine how to communicate those attributes to consumers so they have increased understanding of our sense of place. He says he’s mostly satisfied with the direction the wine industry has taken, though he’s concerned with over-concentration of wineries, tasting rooms and vineyards in some specific areas of the Willamette Valley. His hope, “That we can keep from ‘killing the golden goose,’” to quote Jack Davies of Schramsberg.

Myron Redford

Amity Vineyard

Myron Redford arrived in Oregon a self-prescribed Pinot Noir “freak.” He met Jerry and Anne Preston, then owners of the Amity Vineyards site — planted in 1971 — through a friend. He befriended the couple and meanwhile experienced David Lett’s first Pinot Noir, 1970 Oregon Spring Wine. When the Prestons divorced in 1974, Myron jumped on the opportunity to buy their vineyard.

Lett’s first release, especially when he tasted it again a year later, greatly impacted Redford. He also had tried Richard Sommer’s wines and was impressed with his Pinot Noir and Rieslings. Focused on Pinot, he also made Riesling in 1976, his first production year. Surprisingly, it was Riesling that kept the doors open at Amity Vineyards, as Pinot Noir was a hard sell in the mid-’70s. Later, he added Gewürztraminer, Gamay Noir and Pinot Blanc to his repertoire. But like most of the early growers, Redford moved to the Willamette Valley for Pinot.

“Oregonians were not as enthusiastic about Pinot Noir then as they have become now,” he says. Redford recalls the story of Dr. Krimier, one of the owners of Hyland Vineyards, Oregon’s original “big vineyard,” who said it best at a meeting in the mid-1990s. “Will you wineries make up your damn minds? We planted Pinot and then you asked us to graft it to Riesling. Now you want it converted back to Pinot Noir?”

In his eloquent way, Redford describes the early days: “At the beginning it was all ‘a wing and a prayer.’ Except for Bill Fuller at Tualatin, none of the original group had been a winemaker, and we were there searching for the Holy Grail, not for profit.”

He speaks about the beauty of the camaraderie, how the sharing and the devotion to Pinot Noir as the long-term goal made the industry what it is today.

When looking to the future, Redford still roots for the underdog. “For me, the excitement is still with the cellar rats who are making a little wine on the side for their own brand. It’s these small guys that carry on the Oregon tradition and spirit.”