Peak Interest

Testing the extreme edge of winegrowing in the Blue Mountains

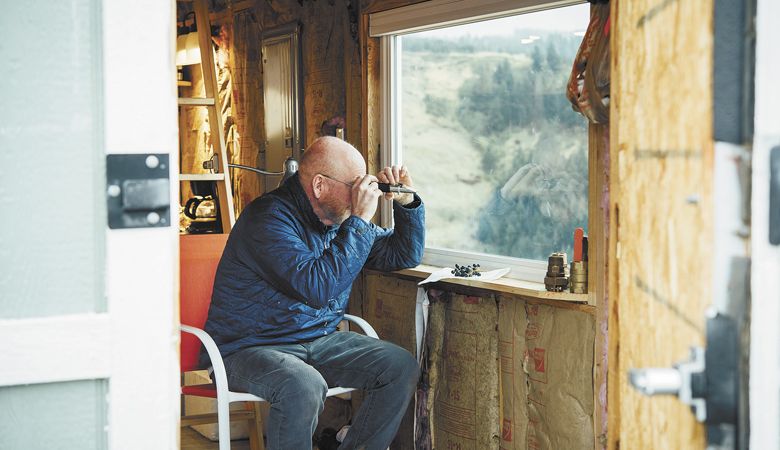

While some bucket lists include extreme items such as “moving to Tuscany” or “partying with Oprah,” Dean Richards’ checklist appears quite ordinary. Yet to those who know viticulture, it’s just as extreme: In 2018 and 2019, Richards planted a dozen grape varieties at 2,882 feet above sea level.

The Lewis Peak Experimental Vineyard (LPEV) project aims to determine which varietals will reach physiological ripeness at this lofty elevation. He plans to eventually farm without irrigation and also make a little Cabernet Franc down the road.

“People keep telling me: ‘The future of the Walla Walla wine industry is dry farming on the slopes of the foothills of the Blue Mountains.’ We’ll see,” Richards says.

A retired Portland trial attorney, Richards’ affinity for Walla Walla Valley wines began with an auction at his daughter’s school. “Someone brought a 1994 or 1995 Woodward Canyon Charbonneau Red, and it lit me up.” A couple of years later, he tasted a Cabernet Sauvignon from Pepper Bridge, and the light sparked again.

These “a-ha” moments motivated Richards to begin regular treks to southeastern Washington. “I was too busy with my law practice up until then to really scope the place out,” he says. He tasted more and more Walla Walla wines and found himself volunteering for the occasional harvest. He closed his law practice for good in 2008.

“Walla Walla was on my mind,” Richards says. “I loved the wines, the people and their wine culture. From the very beginning, I felt like I belonged there. By 2012, buying land and trying to grow grapes in Walla Walla was near the top of my bucket list.”

In 2016, Richards was visiting Woodward Canyon owners Rick Small and his wife, Darcy Fugman-Small, when he noticed a “help wanted” sign in the tasting room. “I was there for spring release, and I brought a bottle of Woodward Canyon’s 1989 Dedication Series Cabernet Sauvignon to share with everyone. I asked Rick if I should apply for the job, and he said, ‘Yes, you should.’”

Two days later, Cory Benz, Woodward Canyon’s hospitality manager, called him. “Are you serious?” Benz asked. Richards drove from Portland to Walla Walla for an interview that lasted all of 30 seconds. He landed the job, with ease.

Richards loved working in the tasting room at Woodward Canyon. “I took it as a sign from the universe that I should cross an item off my bucket list and purchase land for a vineyard.” In July 2016, the same month he started working at Woodward Canyon, he put down earnest money on 22 acres of land on Lewis Peak.

On April 13, 2018, after working on the property’s infrastructure for two years, Richards planted 60 grapevines: 10 each of Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay, Merlot, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc and Syrah. A year later, he planted 150 grapevines consisting of Cabernet Sauvignon, Gewürztraminer, Lemberger, Petit Verdot, Sagrantino and Semillon.

LPEV is located approximately 12 miles east and slightly north of Walla Walla, on a ridge above the tiny town of Dixie. To get there, you drive past old barns and yards filled with rusting equipment; the farms give way to seas of wheat as you climb in altitude. A quaint rural lane suddenly turns into a narrow dirt road so rough and bumpy the State of Washington put up signs rightfully designating it “primitive.” When you arrive at the top of Richards’ property, 3,000 feet above sea level, the only sounds you’ll hear in this rarefied air are the howl of the ever-present winds and blood pounding in your ears.

The view is spectacular. Look up to see a hawk riding a thermal elevator as it hunts for its next meal. Look out over the canyon and watch in awe as the swallows zip about like violet-green foo fighters. Look down to witness a bumblebee emerging from its burrow in the ground. Just be careful if you suffer from vertigo; the slopes here are so steep you’ll feel like you are in Germany’s Mosel region. No matter which direction you look, wild meadow grasses surround the wide open space with no sense of limits. Richards says, “I love how remote, quiet and peaceful it is up there. This place just spoke to me.”

And yet, he had other reasons for selecting this site: Land on the Walla Walla valley floor was too expensive, and neighbors nearby can create problems. “It is just too congested in the Valley,” Richards explains. “Up here, there are no other vineyards nearby to spread pests, pesticides or herbicides.”

Then there is the not-so-little matter of water supply and temperatures. Kevin Pogue, a geology professor at Whitman College, a highly respected expert in the wine industry and owner of VinTerra Consulting, advised Richards early on. Pogue says, “There’s a future here for higher-elevation vineyards because that’s where you will find lower temperatures without having to worry about water issues.”

Debate the causes all you like, but Earth’s temperatures are rising. The Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington reports the average annual temperature in the Pacific Northwest rose by 1.5 degrees (Fahrenheit) in the 20th century and is expected to increase another half degree each decade in the first half of this century.

In the November/December 2016 issue of Wine & Viticulture Journal, Dr. Greg Jones of Linfield College and Dr. Hans Schultz of University of Geisenheim wrote: “Across winegrape regions globally, model results point to a range of 1 to 4 degrees Centigrade warming by 2050–2070, with higher warming rates in the Northern Hemisphere versus the Southern Hemisphere.”

To bring things a little closer to home, Clifford Mass, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington, is working with climate models for specific points in the Pacific Northwest. The ensemble mean of Mass’ models for Walla Walla in a “business as usual” scenario is sobering. If world governments fail to address carbon concentrations in the atmosphere, Walla Walla is looking at a potential increase of 9 degrees (Fahrenheit) in average mean temperature by 2098. It should be noted that Mass’ faith in governmental actions and technology leads him to believe the probable temperature increase in Walla Walla will be 4 to 5 degrees.

No matter the increase, higher temperatures will make an impact. Pogue asks, “Do you want to be California?” He continues, “Climate change is already impacting some growing regions. Those places get so hot, so early, you get wines where sugars and alcohol are too high, and acidity is too low. With a long, drawn-out growing season at higher elevations, you can get more balanced wines.”

Fortunately for Richards, LPEV has a cushion against the heat. At almost 3,000 feet in the Blue Mountains, the daytime summer temperatures are consistently 10 degrees cooler than in downtown Walla Walla. He also faces a different type of growing season compared to the valley floor.

A few years back, Pogue placed weather monitors on Lewis Peak at 2,500 to 3,000 feet. He received some exciting data. “The heat accumulation surprised me, and the first freeze/frost dates were considerably later than the valley floor. Your potential growing season up there is longer, and you can let fruit hang until late October. A longer, gentler growing season can help create wines with more balance. The sugars don’t get ahead of phenolic ripeness, and you don’t lose acidity,” Pogue explains.

At 2,882 feet, Richards’ experimental plot benefits from more than just cooler growing-season temperatures. Timothy Donahue, director of winemaking at College Cellars, explains, “Once you go above 1,100 feet, you don’t see the frost damage you do at lower elevations.” Richards agrees, noting his winter lows are higher than those in the Valley. In the winter of 2018, the lowest recorded temperature in his vineyard was 9 degrees, while the Valley was hit with temperatures closer to zero.

Richards hedges his bets by giving his vines a layer of frost protection. Last winter, with the help from a handful of Whitman College students in a Herculean effort, Richards buried the head of each vine with 20 gallons of dirt. He says, “At 9 degrees Fahrenheit, with buried heads, even the Merlot said, ‘So what?’”

Skeptics question whether the site will get enough growing degree days (GDD) at 2,882 feet to properly ripen grapes. Richards hopes a combination of factors will work in his favor. First, the property faces 16.5 degrees directly into the southern sky. The higher elevation also means the sun’s ultraviolet rays will be more intense than they are on the valley floor. Second, the soil composition of the hillside is wind-deposited loess over fractured basalt. In some spots, the basalt is within a couple of inches of the surface.

The sun and basalt are critical factors. “With the angle to the sun all day and the basalt retaining some heat, Pogue and I think this will be a good place for some of these grapes,” Richards says.

According to Richards, Pogue did an analysis of GDD in 2009 for another client at a slightly lower elevation on Lewis Peak. The number of GDD at that location was 2384. The same year, Walla Walla registered 2789 GDD.

While the data on GDD at higher elevations on Lewis Peak is limited, the anecdotal evidence looks promising so far. The experimental vines are producing grapes that Richards declares “delicious.” Not content to rely solely on his taste buds, Richards tested sugars on Oct. 13: “The Riesling looks great with nice dark pips; it was at 23 Brix. The Lemberger and Merlot were at 21 and 22 Brix.”

Another advantage Richards has over vineyards on the valley floor is water. “One of the reasons dry farming is becoming a big deal here is the uncertainty over water supplies and access to water rights,” he says.

The uncertainty is justified. Even if Walla Walla only warms a few degrees in the future, the impact on water supplies could be significant. In a Washington State Department of Ecology publication, “Water Smart, Not Water Short,” Blanche Sobottke warned: “A few degrees may not seem like much, but they can make the difference between rain and snow, early or late snowmelt, flowing summer streams or dry creek beds.”

Making matters worse, during drought conditions, the vineyard owners possessing junior water rights in the Walla Walla Valley can lose their allocation to those with senior water rights. Eric Hartwig is the water master for Walla Walla, Columbia, Asotin and Garfield counties. According to Hartwig, more water rights have been granted than there is available water at the moment. “There will always be intense competition for water on the Washington side of the border,” he says.

The situation is even worse for newcomers to the Walla Walla area. Hartwig adds, “Chances of getting new water rights out of the Washington State Department of Ecology in Spokane are slim to none, edging on the side of none.”

LPEV, meanwhile, should have plenty of water. Some 52 years’ worth of data from the closest weather station, the Walla Walla 13 ESE located at 2,500 feet in the Blue Mountains, shows 36 inches of annual precipitation — nearly double downtown Walla Walla’s average.

Hard work, passion and boundless energy have gotten Richards this far. He readily admits the journey wouldn’t have been possible without help. “People have been very generous when it comes to providing information and answering questions.”

His “dream team” of consultants, mentors and friends includes Pogue, as well as Rick Small of Woodward Canyon; Norm McKibben and Jean-François Pellet of Pepper Bridge Winery; Brooke Delmas Robertson of Delmas and SJR Vineyard; and Devyani Isabel Gupta of Valdemar Estates.

Richards recently purchased 200 5C rootstock-grafted Cabernet Franc vines for LPEV’s “phase three.” They are the same clone 11 he planted in 2018. The next step is to plant those vines next spring and find someone to help him make a couple barrels of wine in a few years.

Cabernet Franc remains Richards’ top grape. He fell in love with the wine after drinking ones made in the ’90s at Walla Walla Vintners, Bergeron Winery and Spring Valley Vineyard. “The 2009 Walla Walla Vintners Cabernet Franc is a favorite, but the 2011 Woodward Canyon Estate Reserve might be one of the best Walla Walla wines I’ve ever had. It has 5% Petit Verdot in there, but I count it as a Cabernet Franc,” he says.

Will Richards’ take on Cabernet Franc resemble the Walla Walla wines he fell in love with? It’s unlikely given his unique terroir. “Brooke Robertson tells me I may not get the concentration I personally like. Instead, my wine might be more like something from Chinon or the Loire Valley.” This is good news for those who enjoy lower alcohol percentages and elevated acidity in their red wines.

For those who love Riesling, cross your fingers Richards will plant more. Its potential up in the Blues is enormous. After years of his own research, Pogue says, “In the Columbia Basin, if you were trying to emulate the Mosel and plant Riesling, the foothills of the Blue Mountains would be a good place to go.”

No matter what is planted, Richards wants people to look at his 22 acres as a community resource. He wants people to reach out to him if they are interested in planting their own grapes on his property to see how it grows “on the edge.” That would make Richards even happier than Cab Franc.

Does Richards have any more items left on his bucket list? “Besides helping struggling kids and becoming a better swing dancer, it would be fun to be in on the ground floor of a new AVA,” he replies.

Because it is above 2,000 feet in elevation, Richards’ vineyard isn’t part of the Walla Walla Valley AVA (American Viticultural Area). His future Cabernet Franc label will simply say “Washington.” Although, that may not be the case for much longer.

Robertson predicts people will follow him to the Blue Mountains for the water and cooler temperatures. “Lewis Peak is definitely one to watch in terms of sub-AVAs. It’s a new frontier.”