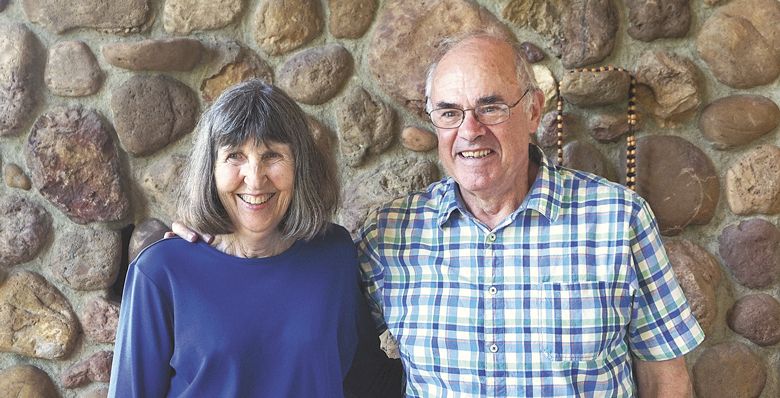

Oregon Wine Original

Wolvertons recall early days of Salishan Vineyards

The Umpqua Valley is credited with Oregon’s first Pinot Noir in 1961, followed by the Willamette Valley in 1965, where the varietal has become internationally acclaimed. What’s less commonly known is that another pioneering spirit took a chance on this rather finicky grape just across the border in Washington state in 1971.

Alongside her husband, Linc, Joan Wolverton also planted Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Riesling and Chenin Blanc, to name a few, with a total of 11 acres under vine at Salishan Vineyards in La Center. Not only that, early vintages received distinguished reviews.

In “Touring the Wine Country of Washington,” authors Ronald and Glenda Holden noted, “Early in 1981, the Wolvertons released the Salishan Vineyards 1978 Pinot Noir, made from their own grapes but produced and bottled by Dick Ponzi at the Ponzi Vineyard in Beaverton. It won immediate attention and was acclaimed in the same breath as the best Pinots from The Eyrie Vineyards and Knudsen-Erath.”

Clearly, the Wolvertons were on to something but, with so little information on cool-climate grapegrowing, the early years were filled with trial and error, and not solely with winemaking.

“Here I was, a city girl. I always lived in cities,” said Joan. “I always took my car to garages. Can you imagine learning to bleed a fuel line to get the air out of it or change a tractor tire?

“I had two babies in the house, and I had steel shanked boots on, and a tractor tire fell on my foot,” she continued. “I somehow managed to get my foot out of the boot after two hours. I didn’t know tractor tires were full of calcium. That’s why they weigh 500 pounds. Wine has been made for centuries, but how you deal with farming, there’s the learning curve.”

What motivated these well-educated Seattlites to purchase 29 acres of farmland and transform it into a vineyard, winery and home with nary a winery in sight? Theirs is a story laced with intrigue.

While studying at Dartmouth, Linc spent time abroad in Dijon, France. His host family owned a vineyard that, according to him, made “very good” house-made Burgundian wines to be served alongside evening meals. Here, Linc met Chanoine Félix Kir, a resistance fighter who became mayor of Dijon and for whom the popular drink is named — still a favorite of Linc’s.

“[The host family] took us to Hospices de Beaune the night before the wine auctions,” recalled Linc. “The royal family of England and the Rothschilds were bidding on this wine, and we’re down there with our wine thieves tasting it.”

Years later while in the Army, he was stationed in Germany and suggested he be transferred to France since he spoke the language. Uncle Sam acquiesced; for eight months of his deployment, Linc returned to wine country, which he’d come to love.

His time in Burgundy remained with Linc, even as he earned a degree in literature and, later, a doctorate in economics from the University of Washington. As Joan likes to say, he then sought out a strong-looking woman to complete his plan.

She admits the real reason she became both the grower and winemaker of Salishan Vineyards was the realization of how costly the endeavor would be; her position as the first female reporter for The Seattle Times simply didn’t provide as much income as Linc’s consulting work.

Immediately, there were weather and soil challenges to address, such as how to contend with botrytis cinera — noble in some grapes but certainly not Pinot Noir — and how to deal with a boron deficiency causing irregularly shaped grapes in early harvests.

Joan recalled that Washington State University’s (WSU) extension agency employed a man, Perry Crandle, who noticed that pears didn’t set well when there was insufficient boron in the soil. He offered up a form of Solubor; once applied to the vines, they had good set from that point on.

Obtaining rootstock was not always easy, either. The initial plants came from Associated Vintners — now known as Columbia Winery — in Eastern Washington, as well as Wente Vineyards and Concannon Vineyards in California. The latter two provided much-needed comic relief for Joan as she undertook the laborious tasks of farming and winemaking.

“The rootstock arrived in burlap bags at Seattle’s Greyhound bus station at weird hours of the night,” Joan recalled. “Loading them into our truck, I always thought how they looked like body bags, and I wondered if I’d get stopped, but I never did.”

Another early challenge was a consistent labor source for vineyard care and harvest. In a town of approximately 100 people, Joan would obtain school and parental permission to hire teens and, in the late 1980s, hired from a pool of strong La Center homemakers. She also added that they couldn’t have brought in the grapes without the help of migrant workers, as well. Because she’d done the work herself, she knew well how hard it was and always paid above minimum wage. To keep all the tasks straight, she gave funny names to each one of them, some of which proved unconventional when relayed years later.

“I was at the La Center library with my grandchildren one time, and this woman recognized me and said, ‘Joan Wolverton, I was one of your strippers!’ That meant they stripped the leaves off. I didn’t run a funny dance show,” Joan laughed.

The eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980 brought Salishan, the closest vineyard to the fallout, other “firsts.” Geologists arriving from all over the country to survey the aftermath bought wine, identified on-site rocks and took vineyard soil samples. The ash itself wreaked havoc on the vines, but it wasn’t all bad.

“It was gritty-like sand rather than powdery ash,” she said. “It was sticking to the blooms, so I called all these extension agencies and went through with a sprayer and blasted the blooms —which you wouldn’t normally do — and hired everyone that I could to pull back the wire and twang it like a bow and arrow to get rid of the ash.

“We did have low yields that year but we were able to save the crop. The 1980 Pinot won a bronze, so it must’ve been a good year after all. During the ’80s, in general, all the wines did well. The vines were gaining in age, but we wondered if the ash in the soil added to better vintages after that,” Joan said.

For all the paving the Wolvertons did for the current generation of Southwest Washington winemakers and vineyard owners, it was time, in 2006, to park the tractor and close the tasting room doors.

“In 2006, I turned 66,” Joan said. “We did our bucket list: South America, Argentina, Brazil. I have grandchildren to watch. It was time to get off the tractor.”

Viki Eierdam is the wine columnist for The Columbian, author of the associated Corks & Forks blog and a freelance writer. She is Level 2 WSET-certified and lives in Battle Ground, Washington.