Oregon via Oenotria

Exploring migration of wine through Italy

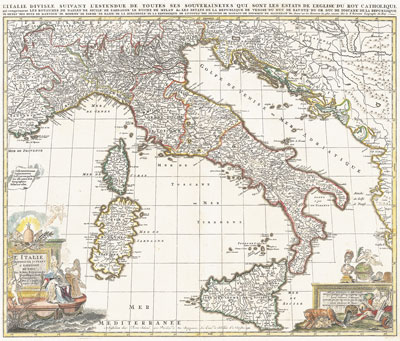

Anyone who ever ordered a pizza from a local Italian restaurant knows, Italy appears on placemats or menus as a great boot, poised to kick the soccer ball called Sicily through the goals once named in antiquity as the Pillars of Hercules. We know the area as Gibraltar today.

What might surprise is the toe of the boot was anciently known as Oenotria, literally, “the land of grapes.” The people of this land, with some modification of the place name settled in the Latium near Rome and otherwise for than some burial art and Pottery Barn seconds, were called Etruscans and soon were absorbed by history and museum display cabinets.

Why any consummation of Oregon wine lore would hang around places like Capri, Naples or Sorrento is a powerful lesson in the story of migrations.

Recorded history refers to people who settle lands they then make arable and productive through agriculture and trade; especially brave in the face of cruel brigands and marauders who rob and despoil such settlements for their own aggrandizement with the requisite pillage, rape, slaughter and tumult

The toe of the boot is a marker on the viticulture trail and wine consumption. The origins of winemaking begin in Shiraz, now modern Iran and once known as Persia. Indeed, under its great emperor, Cyrus, the counselors of state undertook decisions only when sufficiently lubricated with wine — today, theocrats appear to drink only “the Kool-Aid.”

The techniques of vine tending, harvesting, storing and enjoying wine were inevitable outcomes. It translated well to Mesopotamia and the inner valleys of the Holy Land, traveling into Greece and onto islands in the Middle Sea prior to landing on that big toe. From here, wine moved north and then west with the Roman legions. We can guess by the time of the Council of Nicea in 325 AD, the wine trade was well established in France, Spain, along the Rhine and across the fertile lands from the Bosphorus to the westward facing shores of Portugal.

No conquistador set sail from Lisbon or Cadiz without wine and without, in short time, vines to plant as Christendom began its mission to save heathen souls through the usual pillage, etc. Migration continued. Italy, at once so suited to viticulture and enmeshed in the machinations of the great con game, called “organized religion,” marks a high point in the migration and its influence, though haphazard at times, has continued without diminution.

Wine knowledge and custom continued to circumnavigate the globe, as if Ferdinand Magellan were the besotted Bacchus in the Pastoral Symphony segment of Walt Disney’s 1940 “Fantasia.” The pilgrims, landing in what became the Massachusetts Bay Colony, crossed the Atlantic on a wine transport called the Mayflower. Whether or not they inhaled the fumes, the lands to become the original colonies were importers of, and then makers of spirits and wines in the nascent nation. Indeed, the men who argued the merits of independence in the Philadelphia summer of 1776 were sustained by barrels of Madeira wine.

Thomas Jefferson failed with his wine crop in Virginia colony, but this ill fortune didn’t prevent his going broke in large measure from purchasing books and wine from Europe. Drink agreed with our third president; he bought the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon, and then sent Lewis and Clark west to traverse the Oregon Trail around 1804. These actions spurred, in short order, the movement of viticulture.

William Cobbett didn’t even have to leave the East Coast. This on-the-lam Parliamentary radical spent more than a year farming winegrapes on Long Island. Abundant land encouraged farm settlements farther west.

Thomas Lynch of Ohio solved the farmers’ grain surplus problem by making whiskey — he grew rich. Nick Longworth, drunken son-in-law to Theodore Roosevelt and longtime speaker of the house, descended from an entrepreneurial lawyer who transformed the Ohio River into Germany’s Rheingau or Mosel. Indeed, the largest AVAs in the continental U.S. are in the part of the country.

Westward migration brought to California and the Northwest wine technology and an appetite for its consumption by the middle 19th century. The first commercial winemaker in Oregon territory, Peter Britt, opened his barrels in 1859, but the Civil War killed his Jacksonville business soon enough — yet, for good measure, his legacy continues through Valley View Winery.

Nonetheless, the West opened by way of transcontinental expansion and Franciscan priest Junipero Serra, who was to Pacific area wine what John Chapman was to apples. Serra founded missions from the San Diego area to the peninsula at what is now the modern San Francisco, all equipped with vineyards, thus migrating different traditions of viticulture up the coast. The rendezvous was propitious.

This perspective seems necessary as the global commercial ecosystem extended to South America, to Oceania, southern Africa and, as if to complete the great circle, to the recent planting of vines in China’s remote Gobi Desert. The bones of the Huns, Mongols, Seljuks and Tartars have long turned to powder where Cabernet vines now sun themselves — here, barbarian hordes perfected their slaughter and tumult skills; now, descendants of these bloodlines tend grapes.

It appears wine cultivation can survive mullahs and tyrants. Can it similarly find its way to embellish the qualities of life? But can Oregon’s wine industry survive success?

We may admire or deplore the scientific caste system inspired by certain influential critics and marketers to produce an international style of winemaking ruled by celebrity and fashion. However, no doubt remains that money for the global expansion of wine trade follows the pattern of erring hordes but without the pillage and tumult.

Indeed, the aforementioned style has created wine so cultivated and uniform, the nuances are lost in a kind of Oeno-Esperanto way — what works for Coke and Pepsi does not translate into wine glasses.

The greater challenge producers and consumers face involves retaining the qualities of varietals specific to one area, so the traditions extend and wines improve through experience. For the moment, Oregon seems to avoid some of the shoals the tides of fashion inundate — well, perhaps.

The Oregon wine industry did not quite exist when Richard Sommer planted Pinot Noir and other varietals near Roseburg in 1961. The pioneers celebrating 50 years of winemaking did not just open a chain of dry cleaners. They changed the face of the state and its commercial ecosystem. Preserving the spirit that motivated these pioneers is essential to assuring the industry not merely prospers, but manifests its potential. Wine is a totem of Oregon identity that can be sullied by hype and corporate greed. It has happened before, not very long ago or far away.

Wine is a natural resource at its most essential; we must care for its land like Greenpeace enthusiasts care for the sea, but without the confrontational and infantile rhetoric.

So, can you guess the message on the address side of our postcard from Oenetria?

“Don’t blow it.”