Morel of the Story

Family at the heart of Czarnecki mushroom legacy

Sitting in Jack and Heidi Czarnecki’s Newberg living room, I’m surrounded by family — not mine, of course, but one that’d be the envy of most anybody. To my left, Jack; in front of me, son Stefan; to his left, Heidi; and beyond her in the dining room, Minnie, Jack’s spunky caregiver.

-----------------

The founder of The Joel Palmer House in Dayton and mushroom chef extraordinaire suffered a stroke during an operation to remove a brain tumor. While the surgery was a success, the stroke has resulted in some lingering physical challenges. Nonetheless, judging from our conversation, Jack remains as quick-witted as ever and under great care of his loved ones.

For generations, family and food have been at the center of the Czarneckis. In 1916, Reading, Pennsylvania, Jack’s Polish grandparents, Jozef and Magdalena, opened Joe’s Tavern, a saloon complete with spittoons, beer mugs and bowls of mushroom soup for 20 cents.

Jack’s parents, Joe and Wanda Czarnecki, took over the business in 1947, changing the name to Joe’s Restaurant, and gradually transforming it into one of the most iconic fine dining establishments on the East Coast — but wait, I’m getting ahead of myself.

From blue-plate specials to the new menu of lobster and steak — a more continental cuisine — the upgraded dishes attracted an increasingly more sophisticated clientele to the blue-collar neighborhood. Heidi recalls, “I love the story of my mother-in-law who heard a local guy say, “I’m not going in there anymore; I can’t spit on the floor.”

At first, Joe managed the restaurant while Wanda cooked, until an unexpected hospital stay forced her to heal and him to don an apron. Their roles suddenly reversed; they never looked back.

Ultimately, Joe focused on what would become the central ingredient of his culinary legacy: wild mushrooms. “It’s pretty simple: My dad liked to eat out and go to good restaurants,” Jack explains. “He always wondered, even at French restaurants, why there weren’t dishes with wild mushrooms. He had been picking and cooking with them but not too much for the restaurant [at that point].”

The son of a Polish immigrant, Joe grew up foraging wild mushrooms. Heidi says, “Jack’s father was quite the mycologist. Not only did he [eventually] use the mushrooms that he hunted for the restaurant and themselves, but he also did photography, spore analysis and was a member of NAMA, the North American Mycological Association.”

Joe was an expert at identification, too. “When someone at the local hospital had been suspected of eating poisonous mushrooms, they’d call him to identify the mushroom,” Heidi explains. “One time, a family had consumed canned mushrooms that were all poisonous.”

Jack interjects, “Five people were poisoned; two or three people died.”

“They had misidentified these look-a-like mushrooms,” Heidi continues. “They had a little knowledge but not enough to know better. That is something I like to instill in people as it was instilled in us: If in doubt, throw it out.”

“There is an old saying,” Jack elaborates, “‘There are old mushroom hunters, and there are bold mushroom hunters, but there are no old, bold mushroom hunters.”

Following in his father’s footsteps, Jack took over Joe’s in 1974, after his dad had suffered a major heart attack, leading to early retirement. But first, Jack had to change his own course, not to mention move back East from out West.

Jack and Heidi met at Monterey Peninsula College in California. The two fell in love, married and together attended the University of California, Davis, where he studied bacteriology; and she, education, German and music.

One day, they received the news of Joe’s ill health and subsequent uncertainty of the restaurant’s future. Heidi remembers, “He said, ‘If you want this business, I will keep it running for you. If you don’t, I’m going to sell it.’ Well, we weren’t sure exactly what we were going to do be doing [after graduation], so we thought, ‘You know, we should not dismiss this so quickly.’”

During the following summers, Jack and Heidi worked at the restaurant. After commencement, they made it official: “We decided to work full-time with Jack’s parents until it was time to take over the business,” Heidi says.

Above the restaurant, the young couple moved in with Jack’s parents and grandmother, as well as Heidi’s sister who’d come along for the ride. For one year, all five cohabited, but the soon-to-be owners lived there another four years, learning all the dishes and soaking in the knowledge needed to continue Joe’s success.

And yet, it wasn’t all work. “We would go mushroom-hunting with Jack’s parents all over the place, even up to Canada,” Heidi explains. “We would pack picnic baskets with a bottle of wine and make a day of it. Nothing is better than having the back of your car loaded up with wild mushrooms.”

With mushrooms center plate, Joe’s continued its reign and Jack was recognized for his culinary contributions in The New York Times, Washington Post and People Magazine, to name a few.

Prior to the superb reviews, Jack’s reputation was already on the rise. “Like a lot of great things that happen in your life, it begins with, ‘One day, the phone rang,’” he says. “It was a call from the Union Club (The Union League of Philadelphia). Hoity-toity, blue-blood Philadelphia types… The man on the phone said he had a specific request from one of my old professors at [UC] Davis who was having a big celebration [at the club]. His name was Maynard Amerine; he taught enology and viticulture [courses]. He knew I was in the restaurant business, so he was curious to have me there. So, I did.”

Subsequently, Jack started receiving more requests, including being a judge at wine tastings. He became a regular at the International Eastern Wine Competition in the Finger Lakes of New York. “I would drive there every year for my one-man vacation,” he fondly remembers. One of his fellow panelists was Judy Peterson Nedry of Chehalem Wines — now under ownership of Stoller Wine Group. In fact, she was the one who suggested the Willamette Valley, when the Czarneckis started entertaining the idea of moving west.

After many years of running Joe’s, creating a second restaurant, Joe’s Bistro 614 in West Reading, and becoming THE nation’s mushroom culinary expert — Jack was named one of the six most innovative chefs in the U.S. by Town & Country Magazine in 1982 — he and Heidi wanted a change of scenery, perhaps a return to California where she was raised and the two had met.

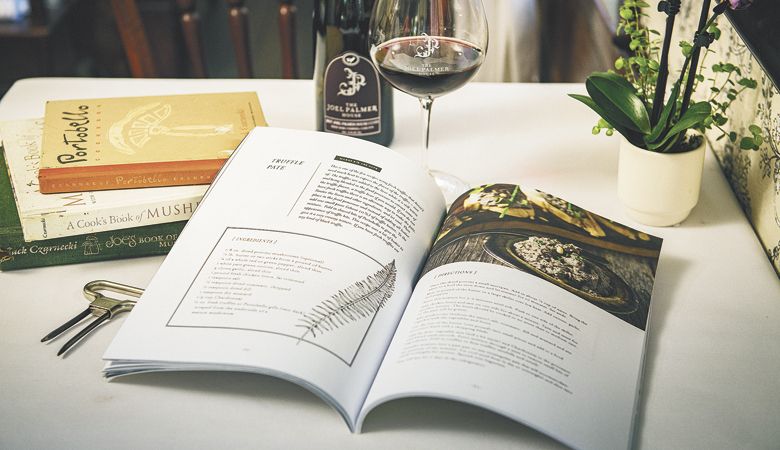

The idea of relocation surfaced after a West Coast book tour of Jack’s second book, “A Cook’s Book of Mushrooms,” winner of a James Beard Foundation award in 1996 — some 10 years earlier, he’d published “Joe’s Book of Mushroom Cookery.”

Researching real estate and running the numbers, the Czarneckis explored California but kept Oregon in mind. Jack remembers, “During the [book] tour, a mushroom fanatic named Maggie Roger showed me around [Portland]. I knew who she was, and she knew who I was, but we had never met before.”

Heidi adds, “Oregon really appealed to us with the mushrooms. Jack was already in tune with a lot of the mushroom people out here. It’s just a mushroom heaven, and wines, too, of course. We both saw a great potential for growth.”

In 1996, the Czarneckis arrived in Dayton to transform the historic Joel Palmer House into a wine country restaurant. But first, they had major repairs to do and neighbors to convince. Jack says, “Pam McBride, who lived in Dayton her whole life, heard we were coming out here. She went around with a petition asking for signatures to make it possible for us to turn the house into a restaurant and get a liquor license.”

But, why Dayton? Jack recalls his reply to McBride: “’Look around you: the food, the wine, the natural resources.’ I said, ‘Dayton is the culinary epicenter of the universe. Don’t bother, I’ve done the calculations; if you want to know, it’s all tied up in quantum mechanics, okay, and I have proof of that.’”

Truthfully, Jack may have been on to something. Soon after opening in November 1997, the Salem Statesman Journal printed a glowing review encouraging diners in the capital city to take a drive — right up Wallace Road — for dinner. Others in the Willamette Valley, and beyond, followed. The hand-curated, Pinot Noir-focused cellar also added to its wine country allure and prestige.

Wild mushrooms remain center plate under the culinary care of Jack and Heidi’s middle child, Christopher Czarnecki, the head chef and now second-generation owner of The Joel Palmer House. The three-mushroom tart, wild mushroom risotto, wild mushroom soup and beef stroganoff continue to excite diners, alongside Chris’ innovative creations.

While the Czarneckis are experts at finding mushrooms, mushrooms have, at times, found them, too. When the family arrived in Oregon, they had no idea one of their neighbors was Frank Evans, a master truffler and founding member of the North American Truffling Society. He and Jack bonded and formed the self-proclaimed “Mushroom Mafia” with fellow fungi fanatics John Schindelar, Dick Nelson and Chris Chennell, whom Jack met at the International Pinot Noir Celebration in ’97, and Ken Becket, a fellow member of the Oregon Mycological Society. Jack says, “These [men] are my brothers. They are my family.”

As with previous generations, family remains at the core of the Czarneckis. While daughter Sonja resides in Lawrence, Kansas, with her own family, Stefan and Chris live nearby, helping Jack and Heidi when needed. Their wives, Meghan and Mary, respectively, and combined five children also add to the supportive tribe.

While Chris, a former private first class in the Army, continues the restaurant, Stefan leads wine country tourists on truffle hunts and tours of area tasting rooms through his own enterprise, Black Tie Tours. He also maintains production of the Oregon truffle oil — Jack first created 11 years ago — and just recently launched his own canned wine brand, HosBrutality, based on the same-named podcast Stefan shares with two others.

Jack’s sons also stepped up to help their dad finish his latest book, “Truffle in the Kitchen” — self-published in 2019 — when in the middle of the project, Jack required sudden surgery to remove what had been a quiet tumor.

It’s a familiar story for the Czarneckis. Just as Jack helped his own father so many years ago, his sons continue the tradition of family helping family — and mushrooms.

-------------------

Before I turn off the recorder, Heidi, who’d started preparing dinner, returns to the room with a spoon. “Jack is the sauce master, and I need his approval.” Jack leans forward and takes a taste. “That’s good,” he says.

Stefan interjects, “It’s a team effort.” Heidi adds, “Well, we make a good team. We always have.”

Truffles

“It was the middle ’90s when I got my first shipment of Oregon truffles at Joe’s Restaurant,” Jack Czarnecki remembers...

“They are not as strong as the French. I think they are subtler but much more complex,” he continues. “I played around with them a little bit, but I wasn’t very bold; that didn’t happen until I came out here.”

At The Joel Palmer House, Jack started experimenting with both white and black truffles. He says, “That is the fun in cooking: making discoveries.”

Son Stefan Czarnecki explains the culinary conundrum: “When you bite into a truffle, it tastes a lot like a mushroom. But the moment you burp, you can really taste it. So, it’s really the aroma that is so special. What my father discovered is how to get those gases out and bonded to other foods so you can taste it in those foods. Truffle oil. Truffle butter. Foods that are high in fat will take those gases.”

Jack admits some European chefs definitely knew how to infuse food with truffles ages before he did, but the process was not widely known. At the time, the atmospheric method of truffle transfusion was not taught anywhere, nor written down, at least that he could find.

During his trials, mistakes were made. “I probably threw out 200 gallons of white truffle oil during my first experimentation. I tried to do infusion, and it didn’t smell like truffle, didn’t taste like truffle.”

Eventually, he figured it out. Jack shares this knowledge in “Truffle in the Kitchen.”

“I’ve laid bare my soul [in the cookbook],” he says. “I am not trying to hide anything. I think whatever it is you do, you should share it and try to better the world. Put something out there that hasn’t been out there that other people can learn from.”

Beyond books, the family’s truffle expertise has been recorded on film, too, specifically the 2021 movie “Pig,” starring Nicolas Cage. They acted as consultants for the fungi-centered flick set in the woods of Oregon, an environment where the Czarneckis feel completely at home.