Gaining Ground

Willamette winegrowers propose five new AVAs

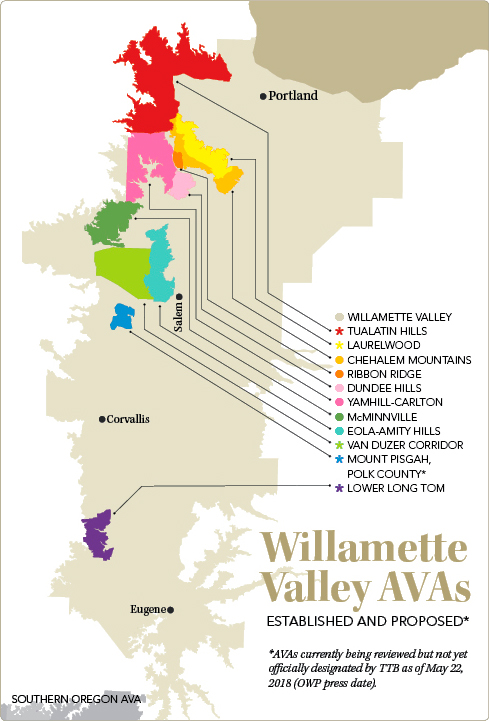

With five new American Viticultural Areas (AVAs) on their way, the Willamette Valley AVA is subdividing faster than Gorbachev’s USSR dissolution. If you have plans to buy a Willamette Valley wine map anytime soon, wait.

Officially recognized by the federal Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), an AVA is a grapegrowing area distinct from its neighbors. When a group of winery and vineyard owners within an existing AVA decide their patch of land is sufficiently unique to merit recognition, they apply for sub-AVA status.

More than a decade ago, winegrowers in six areas within the Willamette Valley, the largest AVA in the state, earned TTB approval of their AVA petitions, including Yamhill-Carlton, Dundee Hills, McMinnville, Ribbon Ridge, Eola-Amity Hills, and Chehalem Mountains. The following hope to join the list: Van Duzer Corridor, Lower Long Tom, Tualatin Hills, Laurelwood, and Mount Pisgah, Polk County.

The AVA creation process begins by filing a petition with the TTB, explaining how an area’s climate, soil types and geology are unique. Proposed boundaries must be justified and the AVA name recognizable to the local community and/or government agencies.

If the TTB decides the petition passes muster, they declare it “perfected” and post it in the Federal Register. The public is then invited to comment about the proposal, after which the TTB will ask for additional opinions, propose modifications or submit a final ruling to the Federal Register announcing its adoption. This process typically takes two to three years.

Since the TTB started the AVA program in 1978, they’ve approved AVAs at a rate of six annually. Numbering 240 in 34 states, the AVA count is likely to hit 250 by the end of 2018. California contains the most AVAs at 139; Oregon currently sits at 18.

Why do people think AVAs are important? The TTB maintains AVAs promote consumer confidence. People buying a bottle of wine with an AVA on the label will know more about the wine’s origin, assuring at least 85 percent of its grapes are grown in a specific area. Winery and vineyard owners also claim AVAs initiate conversations about how the unique features of their region translate to the wine in the glass.

Montinore Estate’s Rudy Marchesi, one of the principal figures behind the Tualatin Hills AVA, looks to Burgundy for a parallel, suggesting the Willamette Valley’s sub-AVAs will become like Burgundy’s village system in the way they guide and educate buyers.

That perspective leads to the pink elephant in the room: Does attaining AVA status mean higher prices? Many owners minimize the money angle by focusing on educational benefits and recognition an AVA can provide.

Not Jeff Havlin. The owner of Fender’s Rest Vineyard is responsible for leading the Van Duzer Corridor AVA application. He says, “One customer already told me they would put our AVA name on their label and pay more for my grapes. That’s why I’m doing it, to make more money.”

Havlin’s intent has numbers to back it. Seton Hall University economics professors Omer Gokcekus and Clare Finnegan studied the period following the creation of the Willamette Valley’s last set of sub-AVAs. They discovered four of the new sub-AVAs outpaced the rest of the Willamette Valley with per-bottle prices rising $1.43 to $14.13 a bottle. According to the study’s authors, there’s a catch: The wineries and their region must have already established a reputation for quality to command significantly higher post-AVA prices. Marchesi agrees with this caveat: “We have to earn it.”

Here are the latest groups hoping to “earn it.”

Van Duzer Corridor

This AVA proposal is a testament to perseverance. The petition was delayed once by lack of supporting documentation for the original proposed name, and again by incoming President Trump’s freeze on new federal regulations. The petition was finally put up for public comments in April 2018, seven years after it was drafted.

The Van Duzer Corridor AVA is 20 miles northwest of Salem, with rolling hills stretching across 60,000 acres. The soil is marine sedimentary with some basalt over siltstone bedrock. While these soils remain unique to the area and impact both grapes and wine, the fortunes of this AVA rest with the wind.

“When the Eola-Amity Hills folks got their AVA, we were miffed,” Havlin confessed. “They were bragging about their Van Duzer Corridor winds, and I’m thinking to myself, you don’t know what Van Duzer winds are until you’re on our side of the Eola Hills.”

Havlin observes how plants respond to the hefty winds and cooler evening temperatures by developing thicker skins. He explains, “The skins are where all the good stuff is. Those skins are why we get a darker, richer Pinot Noir.” Cooler evening temperatures also preserve the fruit’s acidity, helping balance the tannins generated by thicker-skinned grapes.

Wineries in the Van Duzer Corridor AVA include: Johan Vineyards, Chateau Bianca, Namasté Vineyards, Firesteed Cellars, Andante Vineyard, Left Coast Cellars and Van Duzer Vineyards. The AVA also has 17 commercial vineyards, with 1,000 acres of grapes planted to everything from Pinot Noir to Zweigelt. The number of vineyards will increase as Bjørnson Vineyard and California winemaker Ehren Jordan complete new projects.

Mount Pisgah, Polk County

When a small group of winemakers discovered Jackson Family Wines was considering helping create a giant new sub-AVA in the southern Willamette Valley, they decided to launch a preemptive strike and create a smaller one of their own. If successful, their proposed Mount Pisgah, Polk County AVA will be the southernmost AVA in the Willamette Valley.

The AVA covers 5,850 acres, 15 miles west of Salem and home to 10 commercial vineyards, including Freedom Hill, and two bonded wineries: Amalie Roberts Estate and Illahe Vineyards. Mount Pisgah, named by settlers in the 1800s in honor of a hill back home in Missouri, has 531 acres of vines — mostly Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris and Chardonnay — planted from 260 to 835 feet in elevation.

Mount Pisgah features a shallow layer of marine sedimentary soils perched on top of the oldest rocks in the Willamette Valley, Siletz River volcanics. This soil combination exists nowhere else in the valley and contributes to a distinct mineral note in the area’s red wines.

Equally important are the colder temperatures at Mount Pisgah’s higher elevations. These readings are significantly lower than the central and northern Willamette Valley, helping create wines with a lighter touch and elevated acidity.

The Mount Pisgah folks have a different take on wind compared with their colleagues to the north: Less is more. On Mount Pisgah, vineyards are buffered from winds and extreme temperatures, creating what Brad Ford of Illahe describes as a “calm, protected climate.” The information provided in the petition praises reduced wind speeds for minimizing damage to young vines, optimal fruit ripening and avoiding desiccated grapes during harvest.

When I asked Ford about the hundreds of hours invested in this project, he replied: “I just hope federal recognition will make more consumers aware of all the great wines coming off this small mountain in Polk County.”

Lower Long Tom

High Pass Winery’s owner Dieter Boehm chuckled when I asked him about the name of the Long Tom River, explaining it as the result of a misinterpretation of a Kalapuyan Indian tribal name, Lama Tun Buff. Too bad those original settlers misunderstood it because Lama Tun Buff translates to “spank-his-a%$,” which would have made a fine name for an AVA.

Lower Long Tom AVA is located 20 miles south of Corvallis, with 25,000 acres curving along the western shore of the Long Tom River. The application shows 22 vineyards covering 500 acres and 10 bonded wineries, including Benton-Lane, Brigadoon Wine Co. and Antiquum Farm.

Two elements differentiate this AVA: Prairie Mountain and Bellpine marine sedimentary soil. Prairie Mountain’s 3,000 feet divert maritime winds to the north and south, creating nighttime temperatures significantly warmer than surrounding areas. Higher temperatures translate to earlier harvests and Pinot Noir with deep color and earthy, concentrated dark berry flavors.

Bellpine soils exist throughout the region, forming a thin layer of silty clay loam over sandstone once part of an ancient seabed. It drains easily and has limited fertility, forcing vines deeper into the substrate for water and mineral nutrients. Many winemakers in the area credit those extensive roots with creating wines of complexity and significant tannic structure.

Tualatin Hills

This AVA forms a massive 144,000-acre horseshoe shape defined by the Tualatin River watershed and elevations between 200 and 1,000 feet. Within the AVA’s boundaries there are 860.5 acres of grapes and 32 independent growers and wineries including Montinore Estate, David Hill Vineyards, Apolloni Vineyards and others.

The reason for the elevation boundary results from conditions below 200 feet remain sub-optimal for grapegrowing; elevations higher than 1,000 feet have fewer degree growing days and a higher risk of frost. The 200- to 1,000-foot zone is also home to Laurelwood, a reddish-colored soil comprised of weathered volcanic basalt mixed with windblown silt, known as loess.

Laurelwood soils also contain tiny balls of iron manganese called pisolites. Portland State University geology professor Dr. Scott Burns argues the pisolites define the region’s terroir by contributing complexity and rose petal qualities to Pinot Noir. Wines made with grapes grown in Laurelwood are also known for their bright, spicy berry flavors and an elegant texture Marchesi describes as “a more European style.”

In addition to the soil and elevations, the Tualatin Hills AVA lies due east of one of the highest points in the Oregon Coast Range. This location creates a rain shadow effect resulting in lower rainfall totals than surrounding areas. Being less than 50 miles from that range also means chilly maritime winds drop the nighttime temperatures during growing season nearly 4 degrees lower than nearby Portland. The significant day-to-night temperature swings allow for warm days to properly ripen grapes while cool evenings preserve acidity.

Laurelwood

This AVA in the southern foothills of the Tualatin Valley may only be 33,600 acres, but it packs in more than 70 vineyards and 975 acres of grapes. Their list of 25 wineries, including Ponzi Vineyards, Dion Vineyard, REX HILL and Raptor Ridge, reads like a “who’s who?” of the Chehalem Mountains. The AVA stretches from a low elevation of 200 feet to 1,600 feet near the top of Bald Peak and shares a border with the Chehalem Mountains AVA.

While it’s rainier and cooler than its Tualatin Hills neighbors, the proposed Laurelwood AVA shares one significant feature with them. You guessed it: Laurelwood soils. What fascinates me in the Laurelwood AVA proposal, however, is the deep roots discussion.

Vines in this area don’t face anything like big rocks or blocks of hardpan to stop them from driving straight down in search of water. The petition zeroes in on this, stating younger vines situated in the shallow loess will produce high pH grapes with powerfully floral aromatics, dusty tannins and red fruit flavors like cranberry, raspberry or cherry.

As the roots age and dig deeper, they touch the basalt zone. At that point, grapes gain in acidity, acquiring darker fruit flavors and what the petition describes as “violet, lavender, anise, white pepper aromatics, darker and present tannins with a brambly, earthy note.”

None of these AVAs is official yet, but the Van Duzer Corridor AVA could be approved any day now. The other four are still in the perfected stage, but it’s unlikely any will face serious challenges during public comments. Expect the Tualatin Hills AVA to be approved next, followed closely by the others.

Michael Alberty is a wine writer based in Tualatin. He prefers writing about wine over past efforts writing about international environmental politics and major league baseball — because you can’t drink a baseball game and no one has ever professed their undying love to another human after reading about the Montreal Protocol. Michael’s work has appeared in Edible Portland, Willamette Week, Sprudge Wine, Terre Magazine, Wine & Spirits Magazine, The Octopus and on Jancis Robinson’s “Purple Pages” website. He also edits the Oregon section of the annual Slow Wine Guide and covers wine for The Oregonian.

Michael Alberty is a wine writer based in Tualatin. He prefers writing about wine over past efforts writing about international environmental politics and major league baseball — because you can’t drink a baseball game and no one has ever professed their undying love to another human after reading about the Montreal Protocol. Michael’s work has appeared in Edible Portland, Willamette Week, Sprudge Wine, Terre Magazine, Wine & Spirits Magazine, The Octopus and on Jancis Robinson’s “Purple Pages” website. He also edits the Oregon section of the annual Slow Wine Guide and covers wine for The Oregonian.