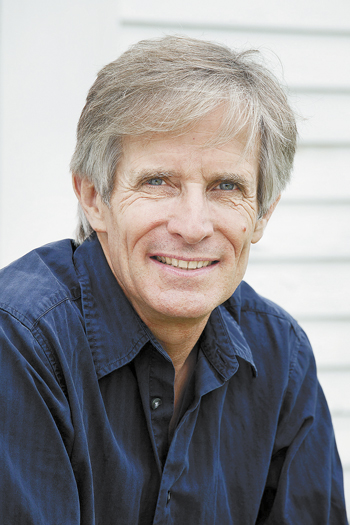

Edward Behr

Q&A with the founder of "The Art of Eating"

Edward Behr is the editor and founder of The Art of Eating, a quarterly magazine first published as an eight-page newsletter in 1986 and now one of the most respected culinary publications. It focuses on taste, especially the connection between flavors and where food and wine is made.

His 1999 article "The Lost Taste of Pork" moved Steve Ells, founder of fast food chain Chipotle, to abandon conventionally raised pork. Chipotle became the first large-scale U.S. buyer of humanely, naturally raised meats.

Behr’s books include “The Artful Eater: A Gourmet Investigates the Ingredients of Great Food” (1992), “The Art of Eating Cookbook: Essential Recipes from the First 25 Years” (2011), “50 Foods: A Guide to Deliciousness” (2013) and, most recently, “The Food & Wine of France: Eating and Drinking from Champagne to Provence” (2016).

He speaks internationally on food and culture and has contributed to several publications, such as The New York Times, The Atlantic, Forbes and The Financial Times. In 2014, he was inducted into the James Beard Foundation’s “Who's Who of Food and Beverage.”

Behr lives in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom with his wife, Kimberly, and two sons, Maximillian and Zane.

How do you explain the concept of terroir regarding food and wine?

For me — and I apologize for this perhaps uninteresting answer — terroir is about the effects of soil and climate on the taste of food and drink. The human element, which many people talk about now, is charming and appealing, but my own sense of what’s romantic and important about terroir is centered on nature. You can break the concept of terroir down to altitude and exposure, for instance, to the minerals in particular pockets of soil. You can imagine, to return to that human component, cheesemakers on an alpine mountainside needing a big, hard cheese to ship and asking, “How do we make cheese in this cold place?” and then coming up with the methods for Gruyère. But they were responding primarily to nature, including that need for a big, hard cheese to transport over mountain roads. My own interest in food and wine is driven by taste, and nothing is as interesting as the variety in taste that originates in nature.

In researching your latest book, “The Food & Wine of France: Eating and Drinking from Champagne to Provence,” what was the most surprising culinary discovery?

The most surprising food to me was probably the tourteau fromagé, a black-topped goat’s-milk cheesecake that looks burnt and isn’t; it tastes completely delicious. The greatest surprise in a restaurant was when once, in Avignon, the sauce au pistou for my fish was made just for me by hand in a mortar, for freshness and superior texture. It wasn’t an expensive place, and they didn’t even bother to tell me. I just happened to see it from the hallway to the bathroom where there was a window into the kitchen.

What makes a culinary book exceptional?

That the author truly knows the subject from familiarity over a long time or from digging deep recently. That the author feels the importance of the subject strongly — I mean, something much more specific than a “passion for food.” That the writing is clear, well-organized and tight.

What is the one cookbook in your library you can’t live without?

Short answer: None. When I cook, after all these years, I’m more likely to turn to one of my shorthand recipe cards than to look at a cookbook.

Long answer: I love good cookbooks, and for me, although it doesn’t speak to our present times of diverse cultural influences, the best cookbook is Richard Olney’s “Simple French Food,” first published in 1974.

What is a meal without wine?

Especially at dinner, when I don’t have wine at a meal I find myself, physically, wanting to reach for the glass that isn’t there. I miss the flavor interaction, the refreshing acidic counterpoint. A meal without wine, or at least a Western meal without wine, lacks dimension.

You have the opportunity to eat and drink with three culinary/wine personalities whom you’ve never met. Who’s at the table? Which dish do you prepare/order? Which wine do you open?

Let me work backwards. I’d opt for a pre-phylloxera wine and, since this is fantasy, I’d opt to drink it at a long-ago date: I’d like to know what 1811 Haut-Brion tasted 30 years later. Because I love learning about lost flavors, I’d put that wine with roast beef as it was raised and hung at that time in England for those who could afford the best meat. I’d want the six center ribs roasted before an actual fire. And I’d want the ribs cut long, not short like roasts today in the U.S. Then I’d want people who could really talk about what they were eating and drinking. Maybe the great 19th-century Provençal chef Marius Morard, who would have brought a Southern perspective and, separately, could have talked of the cuisine of his region. Maybe the Neapolitan duke Ippolito Cavalcanti, author of an essential cookbook of his city, published in 1838, for his breadth of experience and utterly non-French sensibility. And then back to France for Alexandre Dumaine, who left his three-star kitchen in 1963, so he knew various kinds of French cooking that are now extinct or all but, and yet he was modern enough that he might have acted as an interpreter of times long past.