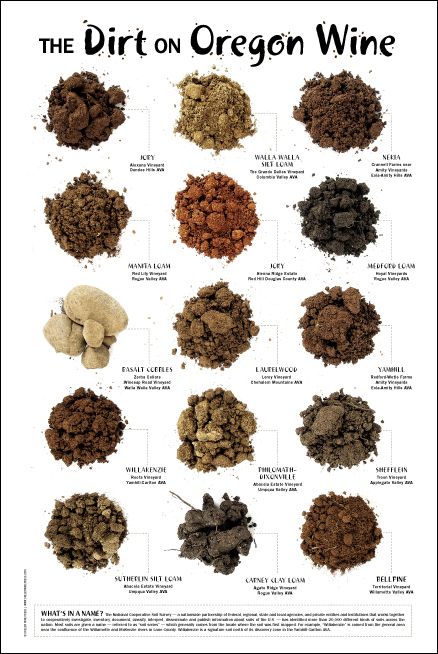

COVER STORY: The Dirt on Oregon Wine

By Jennifer Cossey | Janet Eastman | Mark Stock | Stuart Watson

Willamette Valley

Floods, earthquakes, fire, volcanic eruptions and the movement of oceans and continents. Sounds like the making of an apocalyptic movie. While not an upcoming summer blockbuster, it is the incredible formation of what we know as the Willamette Valley.

The story begins around 200 million years ago when the Pacific Plate started sliding beneath the North American Plate. Much of western Oregon and most of Washington didn’t exist, but over millions of years, the plate left behind shards of its surface, which was once a seabed. The shards continued to build becoming a marine sedimentary landmass. That land eventually became what we know today as Washington, western Oregon and the Willamette Valley — this movement and the development of new land continue to this day.

About 20 million later, a violent chain of volcanoes, the Blue Mountains of Southeast Washington and Northeast Oregon sent tremendous flows of lava into the Willamette Valley, where it created layers of basalt. Eventually with time, erosion, weathering and again, millions of years, the layer of basalt broke up and moved around. The movement of lava was helped in part by the forces of an infamous series of floods.

Between 15,500 and 12,700 years ago, a south-moving glacier clogged rivers near Missoula, Mont., causing Lake Missoula to expand, eventually breaching the glacier’s ice dam and sending massive floods into the Willamette Valley to a depth of 300 feet. The process repeated itself every 60 to 90 years for a total of 36 events. As each flood receded, a small layer of sediment was deposited, covering elevations below 330 feet and producing a fertile valley floor. The powerful floods also helped shape the landscape through land movement and the upheaval of the basalt layers.

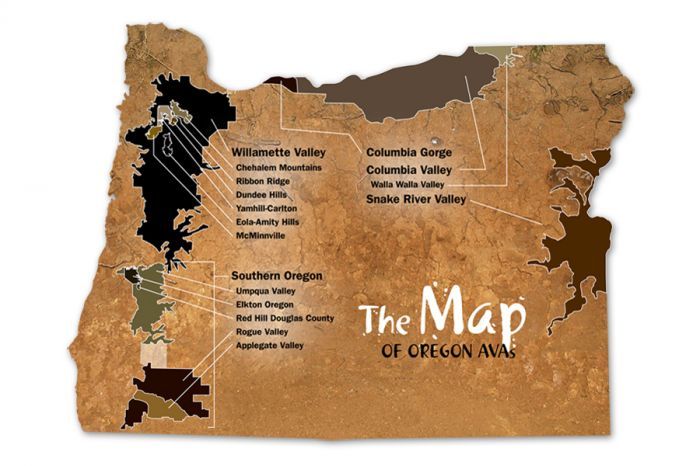

Established in 1984, the Willamette Valley is the state’s largest AVA. Extending from Portland to Eugene, the AVA contains vineyards primarily planted on lower hillsides.

“The main reason Oregon and the Willamette Valley are a fine viticultural area is global positioning. We sit on the western edge of a large continent at a temperate latitude,” said Kevin Chambers, co-owner of Resonance Vineyard. “I believe climate trumps soils, and it’s our climate first and foremost. But our soils are also rather unique and complex. They range from some of the deepest alluvial deposits on Earth, to eroded basalts, uplifted seabed sediments (some with submarine volcanic intrusions), and wind-blown loess.”

The constantly changing structure of the land, unforeseen ecological forces, as well as unpredictable weather patterns and uncertain climates, lead to an actively changing and hard-to-generalize growing region in terms of soil types and wine styles.

Over the years, designations have been established for six sub-appellations in the northern part of the valley, which contains 60 percent of the current acreage planted to vines in the Willamette Valley.

The soil diversity is just one — albeit an important one — of a handful of complicated factors in an equation that results in making the wines from each regions distinct. While climate and topography also play major roles in the character of the wine, the soils and parent materials are crucial factors in what makes the Willamette Valley so unique and perfectly suited for Pinot Noir.

Dundee Hills

The Dundee Hills, established in 2005, encompasses 12,500 acres — more than 1,700 planted to vines — and overlooks the Willamette River to the south and the Chehalem Valley to the north. Protection from the ocean climate is provided by the Coast Range.

The uniqueness of the soils from this region began developing between 15 and17 million years ago when basaltic lava, mentioned above, flowed west from Eastern Washington to the Dundee Hills. While in most parts of this region, the basalt eroded over time and a few ribbons of these ancient volcanic flows remain, the red hills of Dundee and its iron-rich Jory soils being one of them.

About five million years ago, a mass tectonic rise began creating Oregon’s Coast Range as well as an uplift of a single landmass which became the hills of Dundee. The Missoula floods caused a break in the soils and is where the real definition of the Dundee Hills becomes apparent as soils below 330 feet are sedimentary-based while those remaining above that elevation were predominantly volcanic Jory soil.

While many factors contribute to a wine’s flavor, the soil definitely is critical.

“Dundee Hills fruit has more predominant spice characteristics — cinnamon, clove, allspice, cardamom with a dose of ripe plum and cherry,” said winemaker Don Lange of Lange Estate. “These generalizations are influenced by elevation and aspect, to be sure, but the spice from the volcanic Jory soils seems pretty consistent vintage to vintage.”

Chehalem Mountains

Established in 2006, the Chehalem Mountains AVA consists of almost 70,000 acres with over 1,600 planted to winegrapes. It consists of a single uplifted landmass 20 miles long and five miles wide and includes several discrete spurs, mountains and ridges, such as Ribbon Ridge and Parrott Mountain. The Willamette Valley’s highest point is in the Chehalem Mountains on Bald Peak, at 1,633 feet. Three soil types are represented with basaltic, ocean sedimentary and wind- and flood-deposited soils called loess.

The Adelsheim family bought land in what would become the Chehalem Mountains in 1971. “We purchased our first piece of property, now known as Quarter Mile Lane Vineyard, in the great landslide region on the southern slope of the Chehalem Mountains,” said founder David Adelsheim, who was interested in the area for its southern exposure, volcanic soils and the support of his new neighbors, David Lett and Dick Erath.

For him, there really is no single character of the wines from the Chehalem Mountains because of the major diversity in soil, elevation and exposure. But some characteristics have been applied to certain soil types in the region. For example, he says wines from basaltic soils tend to show mineral focused, red-fruited, elegant Pinot Noirs. Those made from fruit planted in loess soils exhibit spicy, rustic, red-fruited wines; and the wines from sedimentary soils can present black fruit and briery Pinots with fine tannins.

Ribbon Ridge

Contained within the larger Chehlem Mountains AVA and home to around 20 vineyards, Ribbon Ridge AVA was established in 2005. The smallest of the sub-appellations, it encompasses 500 acres planted to vines in its 5.25 square miles. The AVA consists of ocean sediment uplift off the northwest end of the Chehalem Mountains and is relatively uniform throughout. The region is protected climatically by the larger surrounding landmasses.

Doug Tunnell, proprietor and winemaker at Brick House, believes Ribbon Ridge’s marine sedimentary parent material, Willakenzie, makes the wine distinct. Tunnell also recognizes some diversity in the soil leading to interesting and special wines.

“The sedimentary clay loam is notable for its mottled appearance and irregular characteristics,” Tunnell says. “If you look out at our vineyard on a clear spring day before all the canopy has formed, you can clearly see that some hillsides are somewhat reddish, others almost sandy white and some appear a darker chocolate brown.

“It is also notable for its variable soil depth. The topsoil in our vineyard ranges from 11 inches to about four feet, depending on location. There are also portions of the Willakenzie series in which a hard shale-like beige colored layer comes almost to the surface, adding to the challenge of root penetration.”

The result of the consistent soils is distinct and recognizable wines from largely low vigor vineyards showing much less leaf than those of deeper soils and thinner canopies for greater air flow and less disease pressure.

“The stresses imposed by this often shallow soil mean the vines tend to harden off faster and concentrate more energy more quickly to the imperatives of reproduction such as forming and ripening fruit,” Tunnell says. “There is a lot of variation from producer to producer, so it’s hard to generalize, but I would say the one consistent trait is a kind of earthiness, underbrush and bramble that I don’t find in wines from other appellations as much.”

Eola-Amity Hills

Established in 2006, the Eola-Amity Hills AVA is almost 40,000-acres with more than 1,300 acres of planted vineyards. The region is adjacent to the Willamette River and composed of the Eola Hills in the southern end and the Amity Hills in the north.

Aeolus, the ruler of winds in Greek mythology, was the namesake the pioneers attached to one of chains of hills surrounding this area and for good reason. The cool, coastal winds making their way into the region by way of the Van Duzer Corridor are largely thought to play a key role in the style of wine produced here. The most prevalent soil, volcanic Nekia, is also a big part of that equation.

The AVA’s soils are rocky, shallow, well-drained volcanic basalt from ancient lava flows, combined with marine sedimentary rock and/or alluvial deposits.

“The common wisdom is that the Eola Hills are primarily basalt, and shallower and more weathered than the Dundee Hills to our north,” said Ted Casteel, founder of Bethel Heights Vineyard and key figure in the forming the sub-AVA. “The generalizations are useful, but the geology of our region has been quite active and remains so, as the Pacific Plate moves east and north incrementally year after year, subducting under the Continental Plate and scrunching up geological features, like the Eola Hills, from the valley floor.”

Casteel went on to explain that not every earth-shaking and surface-changing event dates back millions of years, “We know about St. Helens. One of our first harvests was covered with volcanic ash.”

McMinnville

Established in 2005, McMinnville AVA’s nearly 40,500 acres, 600 covered in vineyards, extends roughly 20 miles south-southwest toward the mouth of the Van Duzer Corridor. The soils are primarily shallow uplifted marine sedimentary loams and silts, with alluvial overlays and a base of uplifting basalt. The volcanic material is some of the youngest in the valley and creates dark, intense wines.

Scott and Lisa Neal, winemakers and proprietors of Coeur de Terre in McMinnville, planted their first vineyard in 1999. They chose the appellation for several reasons, not the least of which was the unique soil composition and weather patterns which they hoped would result in very special wines.

“Diverse soils; this is the true beauty of Mac AVA,” says Lisa Neal. “On a 50-acre piece of property, we have sedimentary, or Willakenzie-like soils, on the lower elevations around 400 feet. Midway up the property — where the Coeur de Terre Rock is located — the soil contains fractured basalt rock layered in ancient sediment. At the upper elevations of the property, we move into the volcanic soils.”

The variety allows the Neals to plant their blocks according to the different soils, producing block-designate wines.

“It is not always easy to put a complete definition around an AVA of our size,” says Scott Neal. “In general, I find the whites from of the AVA to be acid-driven with minerality and highly aromatic. The diversity of whites planted along with winemaking styles generally makes it difficult to get more specific.

“Pinot Noir is a bit clearer,” Scott continues. “Pinots from Mac tend to maintain their acidity and have very robust tannin and color density. The flavor-aroma profile leans toward darker fruits and bramble notes commonly affiliated with a spice characteristic.”

Yamhill-Carlton

Established in 2005, Yamhill-Carlton contains 60,000 total acres and lies north of McMinnville at the foothills of the Coast Range and centered on its namesake towns Yamhill and Carlton. The AVA is surrounded by low ridges in a horseshoe shape called the Spencer Formation, with the North Yamhill River coursing through.

Its more than 1,200 acres of vines are characterized by weather patterns created by the Coast Range to the west — producing a rain shadow — and the protective landmasses of the Chehalem Mountains to the north and the Dundee Hills to the east.

Favored with some of the oldest soils in the valley, Yamhill-Carlton features ancient marine sediments. The coarse grain nature of the soil drains quickly and establishes a natural deficit-irrigation effect, encouraging vines to dive deep into the parent material bedrock for nutrients.

Ken Wright, proprietor and winemaker for Ken Wright Cellars Tyrus Evan Wines, is also an established grapegrower, working with several vineyards throughout the AVA. For him, Yamhill Carlton’s old sedimentary soils make it an especially unique place to make wine, but he appreciates the special attributes of each region and was a key player in the initial formation of the sub-appellations.

“We talk about geology because it has such an incredible influence on the traits you see in the wine,” Wright says. “Back before anybody was really doing single-vineyard [wines], we were, and because we were working with all these different sites, we started seeing these patterns. In a broad, general way, volcanic areas tend to produce Pinot Noirs that are more fruit-focused, and the sediment areas tend to produce more floral and spice elements.

“The ability of the plant to convey and relate to you to its place is just unbelievable.”

Southern Oregon

Climate specialist Greg Jones believes Southern Oregon’s six AVAs represent more soil types and a greater range of landscapes than any wine region in the world.

“It is not like the Willamette Valley, where there is a clear distinction in soils and the notoriously sensitive Pinot Noir shows the differences,” says Jones.

To better understand the six appellations in the southern part of the state, Chris Lake of the Southern Oregon Wine Institute in Roseburg briefly describes each area’s general characteristics and local winemakers reveal a favorite wine made from grapes grown there.

The 2.3-million-acre Southern Oregon AVA was established in 2004 to join the already established Rogue Valley and Umpqua Valley regions. The vast territory includes a series of high intermountain valleys sharing a warm, sunny, arid climate and contain old, complex soils derived from bedrock.

Winemaker Linda Donovan, of L. Donovan Wines and Pallet Wine Co. in Medford, works with 39 varieties of grapes grown in decomposed granite, river rock, and heavy clay across Southern and Central Oregon. Tolo series, which is mostly fine loam but can vary in texture, is most prevalent in the Rogue Valley.

“We select sites that have the right aspect, soils and climate for the wines we want to grow, and we amend soils as needed and irrigate accordingly,” says Donovan, whose favorite local grapes are Grenache and Pinot Noir. “The best farmers are ‘wine-growers’ and it shows in the bottle.”

Umpqua Valley

The Umpqua Valley AVA, established in 1984, consists of 693,329 acres in Douglas County. These soils are composed of gravelly and coarse-textured material deposited in the river floodplain. It is warmer and drier than the Willamette Valley but cooler and wetter than the Rogue. Many of the valleys run east to west, driving cool maritime air flows far inland from the coast during most of the growing season.

Abacela owner and winemaker Earl Jones — and father to Greg Jones — has experimented with five major soil types outside Roseburg.

“Since 1997, many of our finest estate and reserve Tempranillo bottlings have been sourced from Klamath terrane soils, namely Sutherlin silt loam,” says Jones. “Our finest Syrahs are sourced from the other side of the Safari Fault line in the Oregon Coastal terrain’s South Face block. These soils range from coarse gravel to very coarse cobbled in texture, but the extreme steepness (42 percent slope) and solar insolation likely contribute a great deal to the wine quality.”

Red Hill Douglas County

The Red Hill Douglas County Oregon AVA, established in 2005 within the Umpqua Valley AVA, is a rare single-vineyard and single winery appellation. Wine producer Wayne Hitchings of Sienna Ridge Estate owns all 450 acres of undulating vineyards that rise to 1,200 feet in the 5,552-acre appellation. The Red Hill microclimate is one of a large number of different climates along Interstate 5 caused by landforms and elevation variations.

Red, pebbly volcanic Jory series soils up to 20 feet deep create tight and well-formed small clusters that increase the flavors and structure of Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon and a dozen other Sienna Ridge Estate red and white wines, including a soon-to-be released méthode Champenoise sparkling.

Elkton Oregon

Elkton Oregon AVA, established in 2013 within the Umpqua Valley AVA, has 74,947 acres of low-lying, relatively flat river bottomlands rising to steep slopes. The river floodplain is composed of gravelly and coarse-textured material while the upland areas have shallower soils with reduced fertility and water holding capacity.

Terry Brandborg of Brandborg Winery in Elkton has foothill vineyards at 1,000-feet elevation. The marine siltstone over a basaltic sandstone base provides a “real earthiness in our wines that reminds me of red clay or wet bricks, a rusticity that speaks to me of the wildness of our site and a high-toned, blue fruit character,” he says.

Brandborg Winery Gewürztraminer — praised by The New York Times wine columnist Eric Asimov — is made from nearby Bradley Vineyard grapes grown on alluvial deposits, sand, gravel and silt. “We get wines with a lot of minerality, wet slate with tropical and citrus notes,” says Brandborg.

Rogue Valley

The Rogue Valley AVA was established in 1991 across 1.15 million acres. It has one of the warmest climates in the state and some of the highest elevation vineyards. Soil types vary from thick beds of rock and gravel deposited by ancient rivers and glaciers to rich, deep loams on the flatter sites.

Winemaker John Quinones of RoxyAnn Winery in Medford, who is best known for making award-winning Clarets, says farming requirements are different for various soil types. “Limestone soils are going to have different nutritional and water management challenges than clay soils,” he says.

That said, he adds, “Does limestone somehow directly impart a flavor component different from clay? It does make a good marketing story, but in reality, I don’t think so.”

The major contributors to flavor, he says, come from clone, crop load, climate, exposure, soil nutrition, water management and canopy management. “It’s not the soil as much as what you do with it,” he says.

Applegate Valley

The 278,000-acre Applegate Valley AVA, established in 2000, is the only sub-AVA of the larger Rogue Valley one. The relatively small, narrow valley is warmer and drier than the Illinois Valley and cooler and wetter than the Bear Creek Valley, and its soils are mostly granitic.

Applegate Valley grapegrower and winemaker Herb Quady says sites like Steelhead Run and Cowhorn Vineyards that are closest to the river have coarse, deep, river-wash soils that produce highly aromatic wines.

Adjoining these sites are the more fertile, loamy areas, such as those owned by Bridgeview Vineyard and Winery, Longsword Vineyards and Valley View Winery vineyards, where soils are generally fine and rich.

Higher elevated alluvial benchlands are coarse and shallow and tend to produce highly structured reds and richer whites. All of the Kubli Bench vineyards are on this soil series, although it also varies significantly.

“My favorite soil series, in addition to the river wash, are the Manita, Ruch and Shefflein series,” says Quady, who makes wine for Troon Vineyard in Grants Pass and is the owner and winemaker for Quady North in Jacksonville. “Our Troon Reserve Zin is planted on a section of Shefflein.”

Columbia Valley

The Columbia Valley AVA, established in 1984, is extremely large with 11 million acres of land. Most of the AVA and its six sub-appellations lie in Washington, with a small section in Oregon stretching from The Dalles to Milton-Freewater. The region is 185 miles wide and 200 long.

About 15,000 years ago, a series of tremendous Ice Age floods, known as the Missoula Floods, deposited silt and sand over the area. These deposited sediments, along with wind-blown loess, make up the area’s present-day soils.

Give a century to Columbia Valley (and Columbia Gorge) wine producer Rich Cushman of Viento Wines, and he might step out on a vine and link wine taste to the soil that fed the grape.

Cushman regards soil differently when it comes to its effect on wine. “I don’t think anybody can ascribe taste characteristics to the soil,” says Cushman. “The things we do in the cellar have so much more impact on wine than the nuanced influence of soil.

“Soil is more about water holding capacity, nutrition, heat retention, whether it’s high nitrogen or low phosphorous,” Cushman continues. “Those will have more impact than the actual chemistry of the soil.”

Columbia Gorge

The Columbia Gorge AVA, established in 2004, straddles the Columbia River for 15 miles into Oregon and Washington, totaling 40 miles in area.

Winemakers in this AVA and the western end of the Columbia Valley all point to Alan Busacca, an internationally recognized soil scientist involved with the Alma Terra and Dreamcatcher labels, as the guy who knows soils best. He holds a doctorate in soil science and consults for the industry through Vinitas Consulting.

He says the three main Gorge soil types include: transported soils, either by wind or the Missoula floods, lying below 1,000 feet elevation; volcanic soils, above 1,000 feet, that are light, fluffy and full of “eruptive materials”; and residual soils, up around 1,700 feet, composed of weathered volcanic rock, often with a clay substrate.

In regard to soil’s impact on flavor, he feels inadequate to link the two. “We have three or four main soil types in the Gorge, so by all rights, there ought to be some expressive differences. That said, it’s too early to speak with any confidence. Check back in 100 years.”

Like Carey Kienitz, winemaker at Springhouse Cellars, Busacca is excited to explore the Gorge and learn which of its myriad micro-plots and climatic zones work best with certain grape varieties.

“The positive spin for me is the potential with the complexity of the slopes and moisture — ranging from 40 inches to 6 inches of rainfall — and so many opportunities to try different varieties with the diversity of growing zones that other areas don’t have,” Busacca says.

Kienitz believes, in time, the two Gorge AVAs will be divided into smaller AVAs, to reflect the diversity that now only complicates AVA identity.

Walla Walla Valley

Fur trappers are to blame for the first vines in what is now the Walla Walla Valley AVA, established in 1984. Rough weather, railroad routes and Prohibition made short work of these brave original plantings. But, with Leonetti in the 1970s came a host of like-minded producers stuck on the region’s extensive growing season, some 190 to 220 days per year. The region — also home to onions, strawberries and wheat — boasts the second highest concentration of vineyards in Washington state.

Part of the larger Columbia Valley AVA, the Walla Walla Valley extends into the northeastern corner of Oregon. Here, in Milton-Freewater, Zerba Cellars harvests an assortment of warm-climate varietals such as Syrah, Petit Verdot and Barbera. Vintner Doug Nierman respects the diversity within the AVA, something he sees, and tastes, via three different vineyards.

The sites exist on the Touchet Formation, or Touchet beds, comprised of drifted ash and silt from old volcanoes (Dad’s Vineyard), rocky cobblestone (Winesap Vineyard) and medium loess set atop basalt (Cockburn Vineyard). Nierman finds a mineral component as well as darker and earthier notes in wines made from vines established in rockier areas. Brighter and fruitier flavors persist in the loess-dominant sites.

The Winesap Vineyard reminds Nierman of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, the world famous village and southern Rhone wine region. Due to the abundance of rocks and lack of true soil at this site, hot weather can prove very costly, drying up the site almost instantly. The rocks themselves coasted in on enormous glacial floods long, long ago.

Set atop basalt bedrock, the Walla Walla Valley has the Columbia River Basin and the Blue Mountains for company. Touchet beds rest on the basalt, up to about 1,200 feet in elevation. Higher up is the Palouse formation containing loess. And while modern development has rid the region much of its rocky terrain, the Milton-Freewater area has protected its alluvial fan, keeping in place resident basalt cobbles.

So long as they’re around, so too will Winesap Vineyard’s propensity for earthy flavor tones.

Snake River Valley

Between 1907 and 1939, a mine near the Cook Family Ranch in Baker City extracted gold and copper from the valley near the Elkhorn Mountains. Today, the northeastern Oregon site is home to Motherlode Cellars, a family operation devoted to high-elevation Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Conoice.

At 3,400 feet, it’s one of the highest vineyards in the region, but that’s precisely why viticulturist and Motherlode winemaker Travis Cook adores it. “The elevation is so high it tends to let the fruit hold on to its acids, unlike the Columbia Valley area that tends to easily achieve overripe fruit qualities,” Cook said. He cites the warm winds as well, noting their hardening effect on the canes, limiting disease pressure in the vineyard.

The Snake River Valley AVA, established in 2007, is 8,000-square miles located mostly in Idaho, but also in Oregon’s Malheur and Baker counties. It’s a rift valley situated on the west end of the Snake River Plain, Idaho’s agricultural beating heart. Long before the mining of precious metals — about 3.5 million years — this vast swath of high country held Lake Idaho, which, coincidentally, reached depths of roughly 3,400 feet. The lake gradually drained and a series of colossal floods caked the region in sediment. Silty, sandy loam and loess deposits — along with the occasional ancient volcanic cinder cone — remain.

Cook appreciates the accessibility of resident soils like Clover Creek and Keating. “They are easy to work up and break apart,” he said. “Cultivation is done with relative ease.”

Harsh winters and fringe frosts don’t make things easy, but the resulting flavor profiles in Snake River Valley wines are worth the headache. Just 10 inches of annual rainfall ensure the sunburned hue and relative coarseness of the earth here.

“From the reds I get a lot of molasses and wild berries,” added Cook. He mentions tropical fruit flavors like pineapple and passion fruit from the whites, a far cry from the green apple or pear accents one might associate with a Willamette Valley counterpart.

Willamette Valley section written by Jennifer Cossey, who is a freelance writer and certified sommelier living outside Yamhill in the northern Willamette Valley.

Southern Oregon section written by Janet Eastman, a reporter for the Ashland Daily Tidings. Reprinted with permission.

Columbia Valley and Columbia Gorge sections written by Stuart Watson. A veteran Northwest newspaper and magazine reporter and editor, Watson owns Watsonx2 Communications in Hood River.

Walla Walla and Snake River sections written by Mark Stock, a Gonzaga grad and Portland-based freelance writer and photographer with a knack for all things Oregon.