AVA Hang Time

Laurelwood District and Tualatin Hills await TTB approval

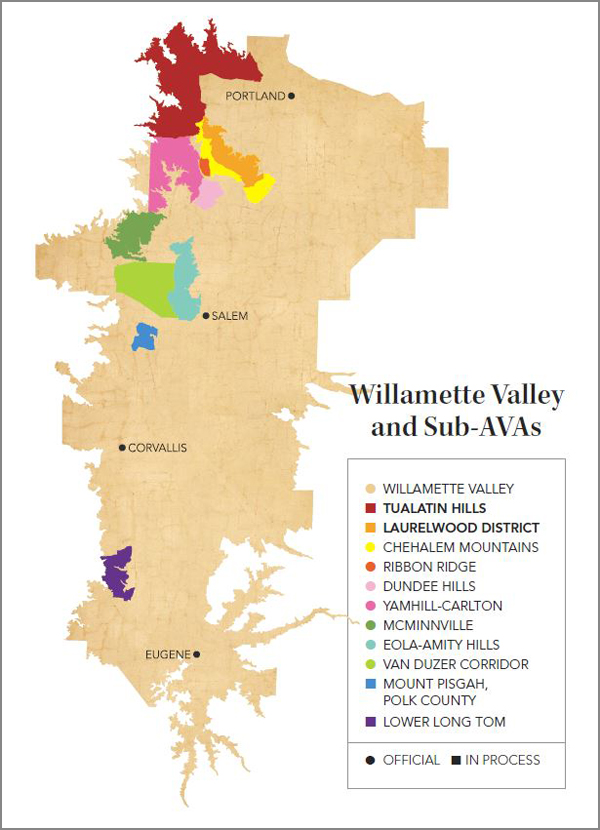

In the northwest corner of the Willamette Valley, the Tualatin Valley was once home to just a handful of Washington County wineries. Now, more than 30 exist with fancy tasting rooms and even more vineyard sites. The area is distinguishing itself apart from other winegrowing regions in Oregon with the proposal of two separate AVAs (American Viticultural Areas), helping define the land’s unique characteristics in this picturesque pocket of the state.

Laurelwood District AVA

Luisa Ponzi, winemaker of Ponzi Vineyards, and Ron Johnson, founder of Dion Vineyards began the process of creating the Laurelwood District AVA more than a decade ago. Dion was actually the first vineyard planted in the proposed Laurelwood District AVA in 1973.

Ponzi and Johnson poured over soil maps, defining borders that encompassed where Laurelwood soil is located. Ponzi admits, “As my life became busier, Ron continued to write the entire petition. A decade later, my sister, Maria, myself, Ron’s son, Kevin, and his wife, Beth, decided it was time to file. After a year of speaking to our neighbors, tweaking the boundary to include as much Laurelwood soil as possible and putting the final touches on the petition, we submitted it in August of 2016.”

The proposed AVA is definitely defined by its soil, called Laurelwood, and referred to as “old loess” or wind-blown soil. Ponzi explains that in the Pleistocene period, a mantel of silt, blown into the area from Eastern Washington and Oregon, covered the volcanic exposed slopes on the eastern flank of the Chehalem Mountains. The ground is also influenced from the Missoula floods and the freshwater sedimentary soils deposited onto the hillsides that cover a subsoil of fractured basalt.

According to Scott Burns, professor of geology at Portland State University, “The Laurelwood soil has a distinctive geology upon which it has developed. The bedrock is 15-million-year-old Columbia River basalt — like the Dundee Hills and Eola Hills. It came out of the ground as magma 350 miles to the east and flowed to this position where it solidified. What makes it different from the Dundee Hills and Eola Hills is that it has had the addition of loess (windblown silt) over the past 200,000 years, and it has worked itself into the soil.”

Burns describes the distinguishing characteristics, “The weathered soil from the basalt has combined with the loess to form anold soil (as seen in its red color — noting its age). Formed in the soil are iron concentrations geologists call pisolites — little rounded balls of iron oxides and hydroxides that are sand and gravel size. Found only in Laurelwood soil types, pisolites help define the terroir in the northern Willamette Valley and contribute to the Pinot Noir’s complexity and rose petal aromas.”

The boundary of this AVA is determined by the predominance of this unique soil type within the existing Chehalem Mountains and Willamette Valley AVAs. It encompasses more than 33,000 acres of the north- and east-facing slopes of the Chehalem Mountains, including the highest elevation in the Willamette Valley at 1,633 feet. Initially, they wanted to name the AVA simply “Laurelwood,” but there was already a trademark on the name itself, so the TTB suggested Laurelwood District AVA.

“My hope is that this AVA will better help define a part of the Willamette Valley that is unique due to the soil and the wines that are produced from that soil,” Ponzi says. “As consumers are looking for more information about the products they choose to buy, this AVA will enable us to tell the story of this place and bring a spotlight to the growers and winemakers here.”

Regarding the next steps in the process, Ponzi says, “We’re waiting patiently. There were a few requests on the TTB’s part for revisions and clarification, but nothing too difficult. We are in the final step before the rule is approved or denied. Our hope is to hear by the end of the year, but it could be next spring. It is a long process.”

The wine industry has been overwhelmingly supportive and encouraging of the process. And the public and media are showing great interest and appreciation for helping to define a part of the Willamette Valley often overlooked yet distinct from the rest of the Valley.

Tualatin Hills AVA

Alfredo Apolloni, owner of Apolloni Vineyards, first began thinking about creating a Tualatin Hills AVA as early as 2002 during the meetings for Chehalem Mountain AVA. “[The group asked] if we minded not being included within the boundary of that AVA.” Apolloni explains, “At that time, we felt it was appropriate as we had different and unique conditions in our area, and at some point, we would like to pursue our own AVA.”

Over the years, Apolloni has identified distinctive features where his vineyard is located. “This is a special place defined by its soil and climate. This northernmost 15-mile slice of the Willamette Valley is sheltered to the west by some of the highest peaks of the coastal mountains and shielded to the south by the large mass of the Chehalem Mountains.” He explains that the mountains serve to moderate the Pacific’s maritime climate, providing this cooler spot in the valley more ripening time, and providing a significant rain shadow over the vineyards contained there; especially during the critical months of September and October.

In early 2015, Apolloni joined Rudy Marchesi of Montinore Estate and Mike Kuenz of David Hill Winery, to begin work on bringing forward a formal petition.

They determined that the roughly U-shaped area is also in the protected areas of the northern portion of the Tualatin River watershed; these hillsides are home to most of the Laurelwood soil in the state. “With this in mind, we outlined an area in the Tualatin River watershed with an upper elevation of 1,000 feet and a lower elevation of 200 feet, excluding the urban zones to the east. Superimposing a soil map over this area, we find that it, indeed, encompasses most of the Laurelwood soils in Oregon.”

Luisa Ponzi concedes that the Tualatin Hills probably boast the most Laurelwood soil in the state but believes the Laurelwood District is the most contiguous swath in the Willamette Valley. Additionally, there remains more variation in the age and classification of the loess found northeast of the Chehalem Mountains.

From a marketing perspective, there seem to be benefits for creating these nested AVAs. Apolloni says, “We hope it will help refine the consumer’s definition of unique and special wines produced from our area and its soils as we further define the exceptional and special places that make Pinot Noir in the state of Oregon.”

The proposed Tualatin Hills AVA was published for comment in June of this year and closed in August. Following TTB’s evaluation of any comments made on the submission, Apolloni is hopeful that it will be enacted directly as the eighth AVA within the Willamette Valley.

Other than the logistical hurdles of pulling together a map and submission information required by the TTB, the main obstacle has been the length of time required for review and publishing. Apolloni says, “We received a great deal of help and support from the Oregon wine industry, including pioneers of the Willamette Valley like David Adelshiem, Maria and Luisa Ponzi, as well as Kevin Johnson of Dion Vineyards, to name just a few.”

The more things change, the more they stay the same. It seems the spirit of collaboration within the industry is alive and well.