Vintage Vines

The Glory and Glamour of Old Vines

By Annelise Kelly

Oregon feels rightfully proud of its groundbreaking role in American viticulture. While many of the early adopters in the Oregon wine world planted their vines within living memory–for example, David Lett with Pinot Noir and Chardonnay in 1965, establishing The Eyrie Vineyards– there were also vineyards nurtured by generations long departed. Two celebrated examples are the surviving zinfandel grapevines of Louis Comini near The Dalles over a century ago, and the long-gone vines planted by Peter Britt in Jacksonville in 1854.

While Comini and Britt were true settlers in the covered-wagon sense, industry pioneers such as Lett planted vineyards in the ‘60s and ‘70s. (Even a 1980 vine, planted after the Oregon wine industry was solidly established, is approaching 45 years of age.) These early-adopter grapevines grown and thrived for 50 years or more, and share a singular prestige for many winemakers and connoisseurs.

Similar to humans, older vines possess a stamina and complexity cultivated by decades of perseverance and experience. Many wine aficionados believe old vines produce grapes of exceptional quality, justifiably prized by winemakers and wine lovers alike. “I think certainly there is something special about old vines and the wine they produce,” says Claire Jarreau of Brooks Wines. “If they weren’t, we wouldn’t be talking about them; we wouldn’t be making bottlings for old vine sites or blocks.”

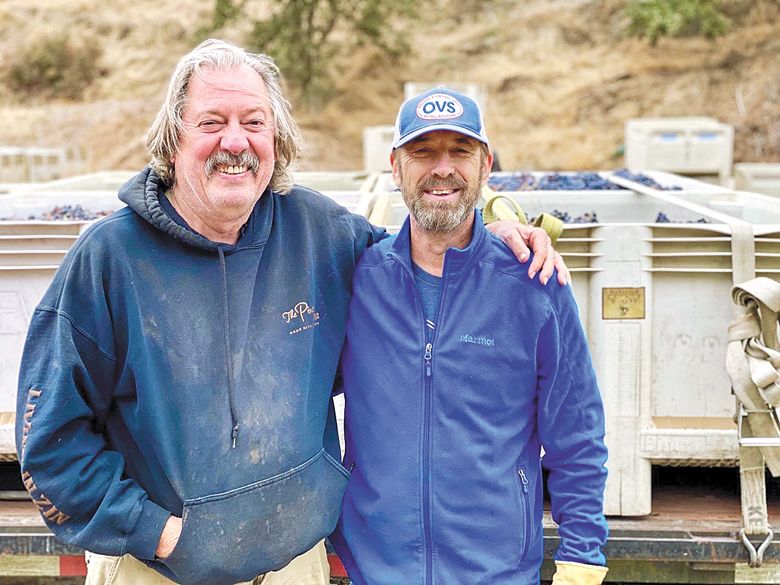

What is it about these vintage vines? Do they merit the mystique? We spoke with five Oregon winemakers for their insights: Claire Jarreau, associate winemaker at Brooks Wines in Amity, where they have five acres of Riesling planted between 1973-75 as well as an roughly four and a half acre block of Pinot Noir planted in 1973 and 1974; Jason Lett, proprietor and winemaker at The Eyrie Vineyards in McMinnville, where the original 1965 block is supplemented by vines planted in the 1970s and 1980s; Boyd Teegarden, winemaker and co-owner at Natalie’s Estate Winery in Newberg, who buys Zinfandel grapes from the 19th century vines at The Pines 1852; Alex Fullerton, winemaker and co-owner at Fullerton Wines in Portland, who works with Pinot Gris planted in 1969, Sauvignon Blanc planted in 1972 and Pinot Noir planted in 1982; and Lonnie Wright, owner of The Pines 1852 Winery and the man responsible for restoring the original vineyard to production. While he doesn’t know the exact age of his seven-acre block of old vines, evidence suggests they were planted sometime between 1890 to 1900.

Old Vines: Vive la différance

After a few decades, old vines show some distinct physiological advantages over younger counterparts.

The primary reason why old vines perform differently from young vines originates in their root structure. These roots have dedicated decades burrowing deep in search of water and nutrients. Robust, expansive root systems enable the plant to reach remote layers and a greater variety of substances in the soil. They also have better access to year-round moisture within the layered depths.

Over time, older vines adapt to their environment and become genetically stable, producing grapes well-suited to their specific vineyard location. This genetic stability results in more consistent, high-quality fruit year to year. Some growers observe how older vines tend to develop a superior fruit to leaves, leading to more even ripening and better fruit quality.

Ultimately, these factors contribute to the subtle essence of a vine and its fruit. People focus greatly on terroir, says Lett, “but really, I don’t think vines establish that impression of place until they’ve been there for a good 20, 30 years.”

Fullerton observes, “In general, old vines tend to ripen a bit slower. Very young vines ripen really early, plants that are adapted or maturing will ripen in the middle and old grapevines–given all other constants are the same– ripen a little bit later. You get slightly longer hang time. There’s just a slower development once you have fruit set. They just kind of take their time, physiologically.”

Are Old Vines More Resilient?

Recalling his initial efforts restoring his old Zinfandel vines, Wright says, “I was amazed at how fast they came back to life.” Interestingly, those old plants had no trunks to speak of. “The oldtimers, when they planted grapes up at this latitude, they head-trained them on the ground. They’d leave short canes, basically around a stump at ground level. They didn’t install any trellis because they wanted snow to cover the grapevines, insulating them during the winter months.”

When Wright first encountered them, “they were just bushes on the ground, desiccated. Each bush had one or two live stalks, probably only two or three buds long, and that was it.” These vines, 80 or 90 years old at the time, demonstrated impressive resilience by flourishing quite rapidly once cleared and pruned.

Lett muses, “Maybe resilient isn’t the word… perhaps, instead, imperturbable? Because they have such established root systems and are going down so far, they’ve tapped into permanent, reliable sources of water. Not even the recent drought years we’ve experienced seem to affect the old, established plants.

Grapevines have two different kinds of roots. The feeder roots are the fine, little thready roots that extend down into the top two, three feet of soil. There can also be several of these enormous, long tap roots that go very, very deep. Their purpose is mining water and, in an old vine, those can be huge.”

“Old vines were established in an era when there was no irrigation,” points out Teegarden. “From the beginning, they’ve had to struggle and strive to find water, whereas an irrigated plant doesn’t have to work as hard. Consequently, you don’t get that root structure diving as deep into the sub-soils in search of moisture.”

At Brooks, Jarreau noticed old vines faring better in the drought conditions during the 2018 growing season. “You know, most of these old vineyards are not irrigated. We had drought stress, and in most cases, signs of shrivel in the fruit,” says Jarreau. However, the sites with older vines and deeper root systems “were able to access water below. The canopy stayed dark green and looked very healthy. The fruit remained much more intact and less susceptible to shrivel.

Having deeper root systems is definitely a consideration as we move into a changing climate where we face more drought and less rainfall. Having deeper roots really benefits the vine, helping it access water and maintain health throughout the ripening season and into harvest.”

Fullerton concurs, reflecting, “We could see that the older the vines were, the better they fared in the extreme 116-degree weather we had in 2021. And, as far as frost issues, if we have an early spring and then experience a cold snap, they are a little bit more resilient, since they tend to bud out later. I believe it has to do with how deep the roots are. That’s traditionally what a lot of people point to when discussing why old vines are better. They’ve got these really deep root networks, enabling the plants to mine from all parts of the soil and into the bedrock versus just the top bit.” It’s a recipe for minerality.

The Fruit of Old Vines

Conventional wisdom attests old vines make better wine because they produce grapes more concentrated in flavor, aroma and character than younger vines.

One reason is lower yields– allowing the grapes to develop more fully and intensely– producing intense, concentrated flavors and aromas.

If vineyards were run by bookkeepers, observes Lett, “they’d say get rid of those old vines; they’re costing you money.” For example, “if you left a younger-vine Pinot Noir planting at a reasonable density and don’t thin it, you can expect six tons per acre. If you do the same thing with an old vines planting, you get two-and-a-half.” If your winemaking is driven by meeting a certain price point, says Lett, “you can’t crop that low. Unfortunately, to make things pencil out, you have to remove the old vines and plant new ones.” However, the flip side is “that’s one of the reasons they’re so imperturbable. They give you the same quality year in and year out because the yields don’t fluctuate as much as in younger vines.”

The fruit itself demonstrates differences, according to Fullerton. He notes fruit from old vines “can hold on to acid a bit better. Your goal when picking is to match up the acidity, sugar level and good flavors. You want those to intersect in the same little window. Old vines seem to do that very consistently in our experience.” He observes that old vines can offer an improved intersection of “riper phenolics, ripe seeds and flavors at the time when the acid and sugar tell us that it’s time to pick.”

Tasting the Product of Old Vines

Wine, like people, becomes more complex with age. This seems to be true with old vines as well.

“With Pinot Noir, I see a difference between older vines versus younger ones,” says Jarreau. “The older vines show restraint– and also their complexity. They aren’t nearly so boastfully fruit-forward and lush… and sort of fun and easy to love. I feel like they ask a bit more of you to really appreciate– and attempt to understand– them.”

“In my opinion, as the root structure penetrates deeper into the soil, you get a wine that becomes more complex and has more dimension to it,” observes Teegarden. “You pick up a lot more nuances from the soils because of the depth of those vines. I find old vine wines usually have a much longer finish. They don’t tend to be as fruity, and have more minerality and earthy notes– more components– making the wine multidimensional.”

Teegarden bottles a handy, side-by-side control group. “From the same vineyard site, I make a Zinfandel from 35-year-old plantings and another from the vineyard portion planted in 1895.” The old vine wine “is a little softer, with more elegance and a much longer, lingering finish than the wine from the 35-year-old vines. The plants are farmed exactly the same. They are actually within 20 yards of each other.”

The Abstract Attraction of Old Vines

There’s no denying the mystique belonging to old vines. When we hear of planting in the 1890s in the Columbia Valley or 1850s in Jacksonville, it’s hard not to crush on them for the sheer romance of their history and uniqueness. Jarreau agrees. “I think that is special– working with these clones that our predecessors also worked with. It’s a glimpse into the origins of our wine history, in addition to the greater complexity in the wine.”

Scarcity contributes to their charm. Old vines predate the introduction of the phylloxera pest. Tragically, some are succumbing to it and must be removed. However, Lett remarks that “California and Oregon are surprisingly rich in old vine planting. In France, they’re extremely regimented about replanting vineyards every 30 years.”

Old vines remain just one factor in crafting a superlative bottle of wine. Lett points out that “young vines can make really good wines. You know, the 1975 South Block that won the competitions in Paris and Beaune in the 70s contained seven-year-old fruit. They’re much more sensitive to, for example, rainfall when it happens. They can produce excellent wines but don’t do so as consistently as old vines.”

Like most aspects of wine, the impact of old vines is detected on many levels: the head, the heart… and the palate. Tasting a bottle of Zinfandel crafted from grapes planted well over a century ago, when horse-drawn wagons and kerosene lanterns were the norm and Grover Cleveland was in the White House, connects us to the labor and vision of true Oregon pioneers.