Unlocking the Secrets of the Vines

OSU’s Southern Oregon Research and Extension Center focuses on growers issues

By Greg Norton

“Oregon has so many Ph.D.s per acre of vineyard working on problems faced by growers, that it’s just really awesome. I mean, you know, we’re all over it.”

Dr. Alexander Levin’s enthusiastic words address the often-unseen ways academic researchers and our state’s wine growers have been “all over it” together in the state’s vineyards for many years.

The history of agricultural research in Oregon dates from the land grant era during the 19th century. Oregon State University’s Southern Oregon Research and Extension Center, or SOREC, in Central Point, began in 1994 with the merging of the Southern Oregon Experiment Station and the Jackson County Extension Service. Since 2016, Dr. Levin has served as an associate professor at SOREC, one of 14 agricultural experiment stations run by OSU. Last month, he became the center’s director.

A Michigan native, Levin, 37, grew up in a suburb of Detroit. As a son of parents who had emigrated from large European cities, agriculture was not part of the family’s history.

His first exposure to the wine industry happened as a server in a fine-dining restaurant while studying psychology at the University of Michigan. Realizing that tips increased when his customers drank more wine, he felt motivated to learn more about it. The restaurant’s sommelier noticed, bringing Levin under his wing. He even arranged some meet-and-greets with winemakers in the Napa Valley when Levin vacationed in San Francisco.

Those connections enticed Levin to move to Northern California, where he worked several harvests, poured wine in a tasting room and attended viticulture classes at the local community college. Briefly, Levin considered becoming a winemaker. But his new Napa winemaking friends persuaded him to instead focus on improving the industry’s understanding of vineyard practices. “That’s where we need to build knowledge,” he remembers them saying. “Their advice pretty much sealed it for me.” He thought, “Well, actually, I don’t want to be a winemaker. I want to be involved in grape growing.”

With that decision, Levin returned to Michigan for an intense, two years of full-time science classes, while working dinner shifts at his former restaurant job. He moved in with his parents and renewed his earlier passion for the STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) disciplines that he had laid aside while studying for his psychology degree. After all that hard work, he attended graduate school at the University of California, Davis, earning a Ph.D. in horticulture and agronomy. Immediately upon graduation, SOREC granted Levin an appointment.

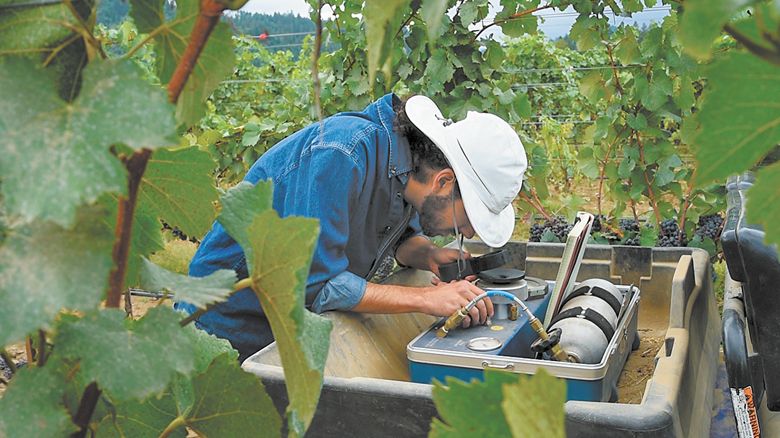

Dr. Levin’s research specialty focuses on water and effective irrigation. Southern Oregon is generally warmer and dryer than wine-growing regions in the northern areas of the state, so vineyard irrigation is more common there. Drought, changes in climate and the region’s aging water infrastructure all contribute to water scarcity and the need to use it wisely.

“In the spring— after the snow melts— we experience our peak… like a giant bucket, and that’s all the water for the growing season,” Levin said. “And, for the past several years, that bucket has been woefully less than normal.”

By vineyard experimentation, Levin seeks to understand how to optimize irrigation practices with the goals of not only conserving water but improving the quality of the grapes— while simultaneously preserving the crop yield and profitability. A certain amount of water stress, at the optimum time during the vine’s growth cycle, can serve all these objectives.

The stations’ findings are shared with the wine industry through presentations at conferences, meetings and vineyard visits. “We can tell them what might happen if they were to do one thing versus another,” he said. “To have that as a resource for the industry, whether it’s myself or our pathologists, agronomist, or entomologist, is really critical, I think, to the past and continued growth and success of our industry.”

Levin points to the collaborative nature of SOREC— and the larger academic structure where it exists— as among the most gratifying aspects of his work.

Having colleagues available with a variety of scientific specialties strengthens the work of the 10 faculty and seven support staff at the station.

Current areas of focus include not only irrigation water management but grapevine viruses, especially red blotch disease, and the effects of wildfire smoke on vineyards. Future studies include vineyard practices with the potential for carbon sequestration and methods to reduce the need for labor— another increasingly scarce resource for grape growers.

SOREC’s work is supported, in part, by the Oregon Wine Board, American Vineyard Foundation and the Oregon Department of Agriculture. “We’re really here to provide knowledge and information in terms of how to solve problems,” Levin said.

To learn more about Dr. Levin and watch a video about his work at SOREC, visit: www.owri.oregonstate.edu/users/alexander-levin.