The Skillful Skiles

By Peter Szymczak

I just fell into winemaking. Cooking is more natural for me,” says Jesse Skiles, the (almost) 30-year-old chef/winemaker of Sauvage Restaurant and Fausse Piste Winery in Southeast Portland.

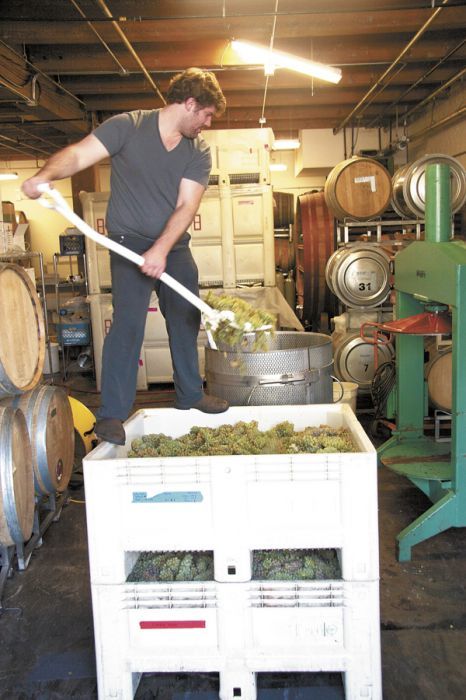

“My favorite days are when I come in in the morning around 7 a.m. and talk on the phone to distributors. There are so many logistics with wine: sales, legal things, labels,” says Skiles, a burly six-footer who speaks with a slight lisp à la Jamie Oliver. “Then I do some cooking, some more winery work, and work on the line at night.”

You’d have to be a 20-, going-on 30-something to maintain the schedule Skiles keeps. While he makes it sound easy-peasy, Skiles is a rarity in the culinary field; he’s one of very few individuals who pulls double duty as both chef and winemaker — and does both exceptionally well.

Location, location, location

Combined, the restaurant and winery occupy a scant 2,800 square feet in a historic building near the east foot of the Burnside Bridge. The kitchen is smaller than the storage closet. The dishwashing station is located in the winemaking facility.

But you’d be wrong to judge the winery-cum-restaurant on either its size or Skiles’ youth.

“I’ve worked in more challenging conditions,” Skiles says. “You’d have to walk down a flight of stairs, go through a door ... a lot of the kitchens in New York are in the basement.”

Indeed, Skiles is exactly where he wants to be — even if he landed here somewhat by chance.

“I’ve maybe gone down a different road than I should have,” Skiles says.

The name he chose for his winery, “Fausse Piste,” alludes to his less-than-predetermined dual career path. It’s a French phrase that literally means “wrong track,” and it has other meanings that resonate with Skiles: “Red herring, wild goose chase, a night of drinking when nothing gets achieved … ”

But don’t read too much into the name. Skiles displays a penchant for humility and nonchalance that is prototypically Portland.

His grandparents moved here, along with his grandmother’s sister and her husband. Together, they owned and operated restaurants.

“My grandparents had one on 23rd, another where Clyde Common is today. They sold them when they had kids,” Skiles says. “My great aunt and uncle kept theirs. It was where Higgins is today. They also owned Joe’s Cellar and the Old Barn — blue-collar places.”

Talk about a culinary pedigree: the McCormicks and Schmicks, and the Schreibers (Wildwood-founding chef Cory Schreiber’s parents) were even on his grandparents’ bowling team!

So, obviously, restaurant life is in his blood; it just skipped a generation — his dad is an urban planner; his mother, a school administrator. But his parents have always been supportive of his culinary interests.

During high school, Skiles washed dishes at Gubanc’s in Lake Oswego — “Well-done, old American classics,” Skiles says. “That’s where I started cooking. It was the busiest restaurant I’ve ever worked in. They would do 300 covers for lunch every day.”

After high school, Skiles graduated from Gubanc’s and joined the kitchen at Henry’s Tavern when it opened in 2002. A year later he moved on to 750ml, a short-lived winebar in Portland’s Pearl District. When it closed, Skiles became serious about pursuing cooking as a profession.

From 2003 to 2005, he attended the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York. “I don’t think culinary school is for everyone,” Skiles says. “If I’d stayed [in Portland] and just cooked, I probably would have been a better line cook. But it was a great opportunity to learn new ideas, meet new people and learn how to operate as a professional.”

A funny thing happened on the way to The Herbfarm

Once chefs-in-training have attended classes for a year and a half at CIA, they are required to seek a six-month externship in a professional kitchen. Skiles considered one of Portland’s then-hottest restaurants, Gotham Tavern, but the admissions department rejected it.

“There was a picture of Michael (Hebb, co-owner) flipping the camera off on their website,” Skiles explains. “They didn’t think that was very professional.”

Instead, the wrong place led him in roundabout fashion to The Herbfarm in Woodinville, Wash. It turned out to be a very fortuitous sidetrack.

Skiles trained with Chef Jerry Traunfeld. “It was wonderful. You’re treated like a true professional there. There’s a lot of respect there you don’t see in other kitchens. That was a more defining experience than any place I had ever worked. The thoughtfulness of all the concepts, the food, was unlike I had ever seen before.”

Skiles also sings the praises of Herbfarm’s co-owners, Ron and Carrie Zimmerman. “They are two of the most passionate restaurant owners. They care about their whole staff, and they’re always there working. They’re so focused on the service, so focused on the food and the wine. I haven’t seen that from anyone else. Some places hire a sommelier or whoever, but they are the driving force at that restaurant. They’re doing service every night, they do field trips, they’re involved in all the new dishes, they’re as into it as the chef and sommelier.”

Wine was also a revelation, thanks to his time at The Herbfarm. “Through my dad, I’d known Oregon Pinot, but at The Herbfarm I got exposed to other things — Washington state and other Oregon wines. They’re probably more responsible for this (winery) happening than anything,” he says.

Once his six months ended, Skiles was offered a job to stay on in The Herbfarm’s kitchen, but he made the tough decision to return to school and complete his degree.

Homeward bound

Culinary degree in hand, Skiles returned to Portland and landed in the kitchen at Meriwether’s restaurant cooking beside chef Tommy Habetz (formerly of Gotham Tavern, as fate/luck would have it). He spent the next two-and-a-half years there.

“It was busy! The patio had 200-plus seats. It’s a small restaurant, but open night and day. We did parties all the time and catering off-site — as opposed to The Herbfarm, which was four set dinners per week with a prep day.”

He left Meriwether’s shortly after Habetz departed. Following a few false starts, he wound up at Owen Roe Winery. “They always keep a chef on. Food is a big part of their culture. They like hiring culinary people with cooking backgrounds to work at the winery, too. At any time, there would be three or four of us on the staff who had cooked professionally.”

Skiles spent the next five years at Owen Roe, preparing lunch every day for the staff, plus private events and two meals a day for a 50-member crew during harvest. “It’s busier than a lot of restaurants,” he says.

During his time there, he learned wine from the inside out. “If you’re cooking there every day, there’s winery things going on, so it’s all hands on deck. After lunch, you’re on the fruit sorting line.”

He was inspired to start his own winery, Fausse Piste, with a focus on Rhône varieties: Syrah, Roussanne, Viognier.

“The Rhône is the birthplace of haute cuisine: [restaurant] La Pyramide, [chef] Fernand Point. A lot of the old-guard Michelin people are from that area.”

After awhile, the size of the winery outpaced what he could produce at Owen Roe, but it was time to move on anyway.

“When I started out, I promised myself I would only work at places for a year or so to get experience, but that never really happened.”

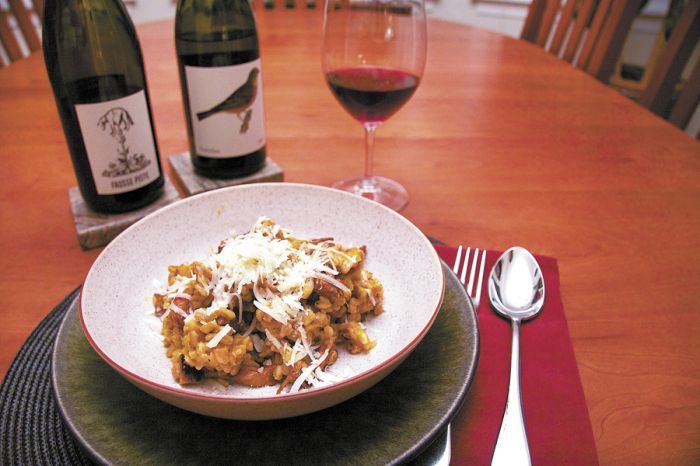

FARRO RISOTTO

Serve this dish at the holiday table in place of stuffing or potatoes. It’s the perfect side to a roasted game bird or as a vegetarian entrée. Farro is a whole grain low in gluten with a nutty flavor and toothsome texture.

Courtesy of Chef Jesse Skiles, Sauvage Restaurant, Portland

WINE PAIRING: 2011 Fausse Piste L’Ortolan Roussanne or 2011 Fausse Piste Vegetable Lamb Pinot Noir

INGREDIENTS

4 cups water

½ tablespoon salt

½ pound farro

½ yellow onion, minced

¼ cup white wine, plus 2 tablespoons

1 tablespoon oil

½ pound Chanterelle, roasted

1 small pumpkin or squash (about 2 pounds), cubed and roasted

6 chestnuts, roasted and roughly chopped

* salt and black pepper, to taste

½ cup Pecorino cheese, grated, plus more to taste

METHOD

1. In a 4½-quart pot, add water and salt. Bring to a boil; then add farro and stir. Reduce heat to a simmer; stir occasionally. Start testing farro for doneness at about 20 minutes. It should be tender with a chewy bite, not mushy — total cooking time should be about 25 minutes. When done, drain farro and reserve starchy liquid — there should be a little more than 1 cup left over.

2. Rinse and dry same pot; heat over medium heat. Add chopped onion and cook, stirring, until softened and slightly browned, about 5 minutes. Add farro and cook, stirring, for 2 minutes. Add ¼ cup white wine. Once farro has absorbed wine, gradually add starchy liquid and stir frequently until all water has been added — it should take on a creamy consistency.

3. In a separate sauté pan over medium-high heat, heat oil until shimmering. Add roasted mushrooms, chestnuts and pumpkin. Season with salt and pepper. Deglaze pan with 2 tablespoons white wine. Add farro and stir until well mixed. Add cheese and stir again. Yields 6 servings.