The Fine Print Pour

Wineries promote transparency by adding ingredients lists

By Paula Bandy

It’s been a long time coming but ingredients on wine labels are nearly here. In 2023, the European Union established new regulations requiring both ingredient and nutritional information. Some wineries, expecting the U.S. to follow suit, are preparing to add this information to their wine labels. Others are waiting for a mandate. The bold have already completed the process of listing ingredients or a scannable QR code connecting to a list on their websites.

Applegate Valley’s Troon Vineyard general manager, Craig Camp, says, “I believe this is the future… consumers want to know more and are very aware of ingredient labeling on all products.”

Nate Winters, Troon’s director of sales, agrees, “Ingredients are indeed a hot topic.”

Which begs the question… what’s really in wine?

For 9000 years, wine was simply fermented grapes. Harvest grapes, throw them in barrels and let them stew ‘til done. Drink. Until recently, most people assumed that was still the case.

Introducing conventional chemical agriculture in vineyards during the early 1970s marked a turning point in grape production. Initially accepted without question, glyphosate, herbicides, fertilizers, and between 60-80 other chemical additives became routine practices in farming, including grapes. However, awareness has increased, revealing the use– or overuse– of these chemicals and their adverse effects on both the environment and human health.

Additionally, chemical oenology additives— flavorings, sulfites and yeasts— contribute a uniformity with the same taste regardless of vintage. It’s a practice some consider lowered the standards of quality winemaking, and wines. Unlike food and cosmetics, required by law to list ingredients, U.S. wines must disclose only sulfites and alcohol content, leaving other additives unmentioned. Grape cultivation and winemaking can involve synthetic substances, raising concerns about the overall quality of wine products. Many consumers now question exactly what is in the wine they’re drinking. They expect specific answers.

Oregon wine rules

The phrase “Oregon does things differently” rings particularly true in wine label regulations. Our state maintains a remarkable set of laws governing not only what’s bottled but how it must be listed on labels, stricter than any other state. Before delving into the specific regulations, let’s first clarify some essential wine terms.

In the United States, the term “American Viticultural Area,” or AVA, refers to an officially recognized wine-growing region. Oregon’s first official AVA, the

Willamette Valley (designated in 1983) remains its most famous. However, why do some grapes grown in Southern Oregon (legally) end up in wines listed as Willamette Valley?

Federal regulations mandate only 75 percent of the grapes must be grown in a state for it to be labeled as such. Our state’s labeling regulations are more restrictive, mandating 100 percent Oregon fruit. And, if a winery wants to list an AVA, the feds demand 85 percent of the fruit must be grown there. Again, Oregon is stricter, requiring at least 95 percent of the grapes originate from the AVA before it can be listed. (This 5 percent leeway allows for grapes grown in another region, such as Southern Oregon, to be included legally.) If a label lists “Oregon,” consumers can trust all the grapes were grown in the state, even if from various growing regions.

Oregon’s laws also extend to how grape varietals are labeled. If a wine lists a specific varietal, at least 90 percent must be comprised of that grape variety. In contrast, federal standards only require only 75 percent. For example, a Syrah from another state might legally contain up to 25 percent of other grape varieties, yet would not be labeled a blend. It’s important to note that Oregon allows an exception for 18 grape varietals traditionally used in blends. They follow the same rules as the feds.

While the specificity of our state’s regulations may pose challenges in terms of competition with other locations— often allowing for lower-priced wines due to less stringent quality control—Oregon wines benefit from more rigorous standards. By maintaining a commitment to purity, Oregon producers ensure higher-quality wine, ultimately preserving their esteemed reputation in the world of wine.

Who’s listing ingredients?

Two Oregon wineries to willingly add ingredient lists are Sokol Blosser Winery and Troon Vineyard.

Located in the Willamette Valley, family-owned and managed Sokol Blosser farms certified organic vineyards and is a certified B Corp. Planting their first vines in 1971 places them at the forefront of Oregon winemakers. One year ago, Sokol Blosser released its first wine with a nutritional and ingredient label prominently listed on the back of the bottle, prioritizing immediate disclosure. All future releases will include this data.

When asked how he feels about Sokol Blosser’s decision to add this information, Camp says, “It takes great courage, and is a wonderful leadership model because they are a larger winery and a lot of people see and drink their wines.”

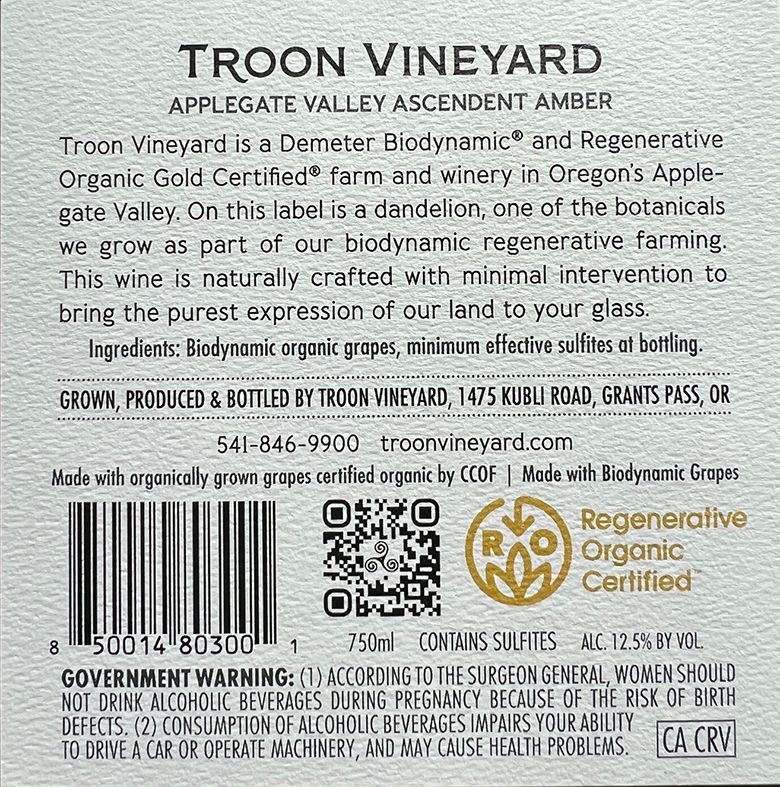

Troon Vineyard originally added nutrition and ingredient information to all its back labels three years ago. A quick scan of the QR code with a phone camera leads to the information online. Winters explains, “The nutritional value comes up first, then ingredients and technical info. Some even have videos and winemaker-tasting notes. And each QR code is specific to that particular wine.”

Troon chose QR codes for their simplicity. Not only do they save space on the label but also allow real-time updates, crucial when exact measurements are not available until bottling.

Troon Vineyard is the only Oregon winery with both a Demeter-certified biodynamic vineyard and a Regenerative Organic Certified winery. In fact, it holds one of only four Regenerative Organic Gold Certifications globally. Camp says, “Sharing wine nutrients and ingredients is just an extension of our general philosophy.

Our packaging has no unnecessary capsules, and uses tree-free labels and DIAM microplastics-free corks. We consider the environment with everything we do and that is evident on the labels. We can list biodynamic wine on our front labels because both our vineyard and winery are biodynamically certified. These are two separate certifications, and we feel an obligation to communicate this to interested consumers.”

Who wants it?

Neither winery can point to a clear increase in sales since adding ingredient information. Regardless, Troon feels it’s important to include the information. One trend is clear: younger consumers demand to know more about products they buy. This shouldn’t be surprising because they’ve grown up with ingredient labels since the mandatory Nutrition Facts Panel first appeared on food packaging in 1994. Now of legal drinking age, they expect transparency on all consumable products. Whether it’s for the curious, conscientious, or concerned consumer, wine labeling, like the elusive proprietary blend, appears to change soon.

Paula Bandy and her dachshund, Copperiño, are often seen at Rogue Valley’s finest wineries, working to solve the world’s problems. She has covered wine, lifestyle, food and home in numerous publications and academic work in national and international journals. For a decade she was an essayist/on-air commentator and writer for Jefferson Public Radio, Southern Oregon University’s NPR affiliate. Most recently she penned The Wine Stream, a bi-weekly wine column for the Rogue Valley Times. Paula believes wine, like beauty, can save the world. She’s also a Certified Sherry Wine Specialist and creates a line of jewelry, pb~bodyvine, offered through boutiques and galleries. @_paulabandy.