Rising Temp

Oregon Tempranillo is increasing in popularity

By Paula Bandy

This summer, wine lovers joined 13 vintners at Abacela Winery in Roseburg, home to Oregon’s original Tempranillo plantings, for a festive day filled with wine, live music and giant, sizzling pans of paella.

Before the annual Oregon Tempranillo Alliance summer event, a private library tasting took place. Tempranillo wines from 2005 to 2018, grown around the state, were sampled and discussed. Winemakers spoke candidly about the wines and vintage conditions, as well as various farming and winemaking techniques.

As the tasting concluded, Nora Lancaster, director and partner at Kriselle Cellars, observed, “You’re seeing the reason why this Alliance was created. So, we can get together to share growing tips and how best to make Tempranillo, along with the idiosyncrasies of our different AVAs. Isn’t it cool to watch winemakers geek out? Here’s to the spiritedness of this conversation and what beautiful winemakers you all are.”

She was right. Tasting these extraordinary bottles while listening as winemakers asked questions, discussed various winemaking methods and openly shared farming techniques– along with their love for the grape– was a marvelous portal into a day of sampling current vintages.

In 2015, the Oregon Tempranillo Alliance, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, was established by four visionary winery owners: Earl Jones, Abacela Winery; Scott Steingraber, Kriselle Cellars; Eric Weisinger, Weisinger Family Winery; and Les Martin, Red Lily Vineyards. With only 350 acres planted in Oregon, Tempranillo’s future was unknown, yet, looked promising.

According to census report figures commissioned by the Oregon Wine Board, during the 20 years between 2004 and 2024, harvested tons increased 1220 percent while harvested acres rose a whopping 664 percent. And, the variety’s planted acreage has risen 28 percent within the last decade, now totaling 450 acres statewide, primarily in the Southern Oregon American Viticultural Area, or AVA. The growth of Oregon Tempranillo shows the steady rise in its popularity.

Old World Grape

The 3000+ year old variety, likely introduced by the Phoenicians to Iberia, is the third most commonly planted grape globally. Recognized for its versatility and deep purple color, Tempranillo achieves peak ripeness before other grapes. In fact, its name originates from the Spanish word temprano, meaning “early.” A well-made Tempranillo has the structure to enjoy now, yet promises a life of two decades or longer, deepening and becoming more plush with time.

Tempranillo Roots in Southern Oregon

Earl and Hilda Jones, legendary pioneer vignerons of Oregon Tempranillo, met while working in the medical field– Earl as an MD and Hilda, a technologist. Together, they discovered a shared love of wine and Spain. Their story is as rich and layered as a glass of Tempranillo.

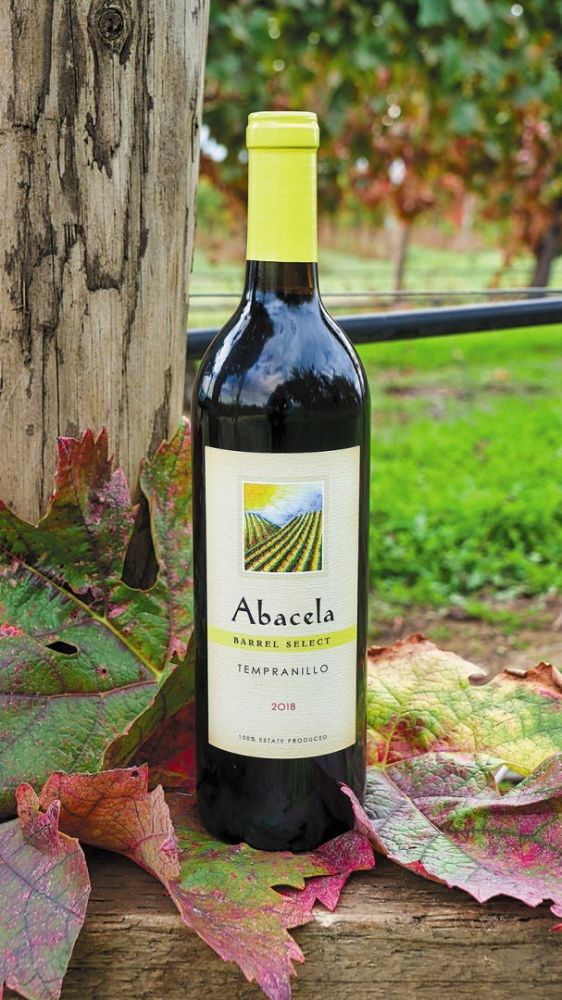

In 1995, after substantial research, trips to Spain and years of study and testing, the Joneses planted a dozen acres of Tempranillo at their new winery, Abacela.

The vineyard site exhibits similarities to those in Spain. Both areas share roughly the same latitude, providing similar photoperiods (the intervals between daily light and dark cycles) and growing season lengths. However, their plan was not to replicate a Spanish wine, but instead craft a distinctly Oregon Tempranillo.

Earl’s son, Greg Jones, PhD, a world-renowned wine climatologist, serves as Abacela’s CEO. He explains, “Many people think being at the same latitude means regions share similar climates. However, regional geography, where warm or cold ocean currents offshore can add more humidity to the air or provide coastal cooling, is key. Europe has two large bodies of water, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, both warmer than the North Pacific. The result is higher humidity levels throughout most of Europe and rainfall all year long in many European regions. The western U.S. experiences wet winters and extremely dry summers. What our similarities in latitude provide are photoperiods and growing seasons perfect for Tempranillo.”

Today, Abacela grows nearly 25 acres of seven unique Tempranillo clones. It’s likely their vineyard has the greatest clonal diversity, along with the most extensive Tempranillo plantings in the state.

California’s complicated history with Tempranillo contributed to Oregon’s niche. Greg describes how most of the West was settled by people of Northern European descent migrating from the Eastern United States with French, Italian and German varieties. Some Spaniards and Portuguese arrived from the South, bringing primarily Mission grapes with them. Somehow, Tempranillo vines arrived and were used in some early experimental growing.

“In the 1880s, UC Davis completed one of the first vine trials. During that period, many cuttings from different varieties were planted in various locations. After observing them for over five years, the researchers decided against recommending Tempranillo. This happened repeatedly in the 1910s, ‘20s, ‘40s and, most recently, in the 1960s,” notes Greg. Finally, UC Davis decided to end further evaluations for California, declaring Tempranillo as “not recommended.” He adds, “They had a poor-quality clone from La Mancha called Valdepeñas, and planted it in places where it either didn’t ripen or over-ripened.

Despite these findings, California does grow Tempranillo, approximately twice as much acreage as Oregon, historically using it in jug wine. Years ago, Earl, after tasting one from California, set out to prove he could do better. “California never developed a Tempranillo wine culture,” Greg reports, “while my dad definitely did something unique, history supplied the opening. That’s why he has Oregon’s 30th Tempranillo vintage.”

Who’s (on) Second?

Rooting around curiously to learn who might be responsible for our state’s second planting, the answer remained elusive until speaking with Rogue Valley winemaker Rob Folin of Ryan Rose Wine.

In 1996, Argentinian-born Felix Madrid boldly introduced Tempranillo grapes in the Willamette Valley, quite possibly the second to do so in Oregon. His low vigor, riparia rootstock vines ripen early while being cold-hardy and phylloxera-resistant– necessary characteristics in the slightly cooler climate. Madrid established Carlo & Julian Vineyard and Winery, named after his twin sons, in 1991. The dry-farmed, six-acre Carlton vineyard, located at 190 feet above sea level, is one of the state’s lowest elevation plantings of Tempranillo. Madrid adopts a traditional Spanish style, blending the variety with other estate fruit, including Grenache and Merlot.

“We get black fruit, and more darkly colored wines here, rather than the lighter colored and red fruit character found in wines from hotter areas. Carlton is warmer because it’s slightly farther from the coast,” Madrid explains, “so our cooling air arrives a bit later in the afternoon. That means we’re marginally warmer for a little bit longer over the growing season, which is significant.”

Places to go, Tempranillo to drink.

Red Lily Vineyards

Applegate Valley

Rachael Martin, Red Lily Vineyards’ founder, owner and winemaker, has grown Tempranillo, the winery’s signature grape for 24 years. She crafts it in five different styles: rosé, an approachable, medium-bodied version, “the heavy hitter” as Martin describes it, a reserve (when the vintage allows) as well as a traditional blend. The Medford native is impressed with the Rogue Valley’s profusion of grape varieties, “There are so many varieties that we can grow well here. But I’ve got my Tempranillo goggles on. My glasses are Tempranillo-colored. I think it’s one of the shining stars.”

Ryan Rose Wines

Rogue Valley

Since first planting his original Folin Vineyards in 2001, Rob Folin has crafted Tempranillo every year but one. Inspired by Earl, who Folin describes as “very charismatic and passionate about Tempranillo,” he was attracted to the idea of planting something unusual. When asked what he enjoys about the variety, Folin replied, “the earthy, kind of dustiness. While it has fruit, it’s not super fruity. I find Tempranillo to be a more savory wine, with prominent tannins and lower acidity. It’s softer and rounder, yet really food-friendly. With mushrooms, it’s a home run, you know? In Oregon, morels and Tempranillo are no joke.”

Valcan Cellars

Willamette Valley

JP (Juan Pablo) Valot named his award-winning 2018 Tempranillo “El Torero” not after a bullfighter, but rather Juan Román Riquelme, his favorite Spanish soccer player. With Argentinian roots from the Mendoza region, Valot prefers full-bodied wines with a “central balance, to be refreshing and have a long finish.”

Achieving that silkiness is part of his wine signature, he says, “it needs to be in barrel at least three years.” He sources his grapes from the Belmont Vineyard in the Rogue Valley. Tempranillo also makes it into his Mélange De Vin, a red table wine blend.

Varnum Vintners

Eola-Amity Hills

When owners Cyler and Taralyn Varnum bought their property in 2018, they knew it was a “slightly historic vineyard in our region.” Cyler describes it as “one of the original vineyards here in the Hills, planted in the 1970s.” The couple purchases Tempranillo from Sunnyside Vineyard, located 40 minutes away, in the South Salem hills. “Planted in 1970, seven rows of vines were grafted with Tempranillo in 2005,” adds Cyler. Varnum Vintners’ 2022 Sunnyside Vineyard Tempranillo is the couple’s best-selling red wine.

Watermill Winery

The Rocks District of Milton-Freewater

Director of winemaking, Israel Zenteno, shares, with a smile, “It’s not easy to farm in rocks. You bend your ankles really bad. Everything has to be done by hand. We go through equipment like nobody else. But the result produces really interesting wines, so we kind of like it.” To be clear, the soil composition is simply rocks, as in ancient stones. The root systems, Zenteno adds, “go really deep and that invigorates the vine itself.” In 2007, Watermill made its first Tempranillo. The vineyard name? Hallowed Stone.

Weisinger Family Winery

Rogue Valley

Based on a conversation with Earl, owner and winemaker Eric Weisinger planted Tempranillo in 2005, mostly clone one. His vineyard, at 2235-foot elevation, might be Oregon’s highest Tempranillo planting. The first vintage, in 2010, Weisinger recalls, “wasn’t great.” But, he shares, “I had a conversation with a couple of Spanish winemakers while overseas. They were singing the praises of clone one, but I explained my yields were disappointingly low. They asked how I was pruning the vines. After telling them, I got a knowing ‘ah,’ along with an explanation for a better way. I’m happy to say our yields more than doubled the following year.” In fact, Weisinger’s 2014 Tempranillo won “Best of Show Red” at the 2017 Oregon Wine Experience.

The Future Looks Fruitful

Tempranillo is now available statewide in over 100 tasting rooms. Our bottlings have earned consistent recognition and awards in both national and international competitions. At Spain’s 2009 Tempranillo el Mundo Competition, the Abacela 2005 Tempranillo Reserve earned the first-ever gold medal granted to an American producer.

Everyone I spoke with mentioned Tempranillo’s versatility and how nuanced the grape expresses its terroir. Cyler observes, “Because it is so adept as a wine to terroir, Tempranillo is like the chameleon of the wine world. It is incredibly adaptable.”

Today’s climate opens the door for warmer-loving varieties. As a heat-tolerant, early ripener, Tempranillo is positioned to be a sought-after grape. “The north is growing into it,” observes Greg, “It appears to be a rather flexible variety, managing moderate drought and heat well, especially in Oregon, where it thrives in a range of growing conditions.”

Innovative farming practices, designed to mitigate climate change, are occurring in the vineyards. Adaptability is key for those dedicated to the future of wine.

Permanent Planting

Not long after the Joneses planted Tempranillo, the couple attended a wine industry party. A well-known winemaker asked Earl what they planted. He responded, “Tempranillo,” receiving only a nod in return. Later that evening, another winemaker declared, “You know, Earl, you can’t really plant grapes temporarily.” Earl, smiling, replied, “It’s tem-pra-KNEE-oh,” leaning down and placing his hand on his upraised knee, emphasizing the pronunciation. And, as we have learned, it was never meant to be temporary.

Paula Bandy and her dachshund, Copperiño, are often seen at Rogue Valley’s finest wineries, working to solve the world’s problems. She has covered wine, lifestyle, food and home in numerous publications and academic work in national and international journals. For a decade she was an essayist/on-air commentator and writer for Jefferson Public Radio, Southern Oregon University’s NPR affiliate. Most recently she penned The Wine Stream, a bi-weekly wine column for the Rogue Valley Times. Paula believes wine, like beauty, can save the world. She’s also a Certified Sherry Wine Specialist and currently sits on the Board for Rogue Valley Vintners. @_paulabandy.