Cheers to 40 Years

Celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Willamette Valley AVA

Story by Annelise Kelly

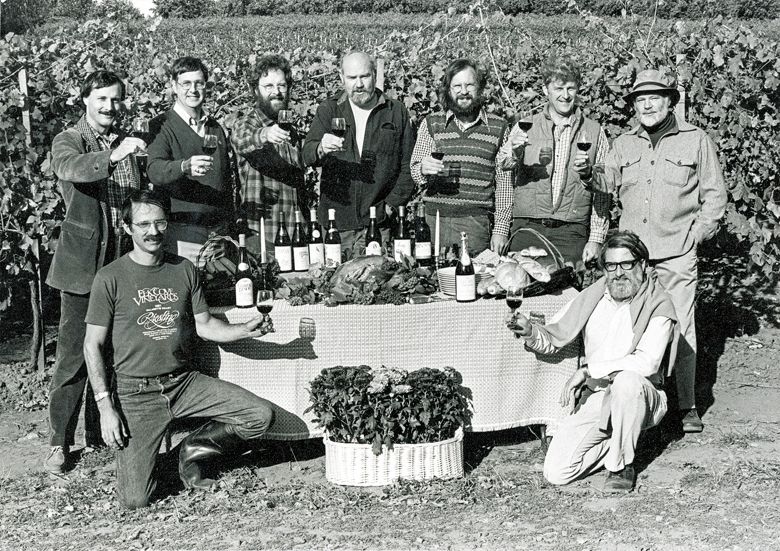

When a small group of curious, passionate wine enthusiasts planted the first grapes in the Willamette Valley in the ‘60s and ‘70s, it’s unlikely they anticipated what the future held. Oregon’s wine would soon earn a glowing reputation on the world stage– the area rapidly became synonymous with high-quality Pinot Noir rivaling the best from France.

Many of these early oenological pioneers emerged with an education in wine from U.C. Davis and a maverick notion that Oregon might be a hospitable place to grow cool-weather varietals. The results were a resounding success, and wineries flourished, popping up like chanterelles after a fall rain. The Willamette Valley had five wineries in 1970; 34 in 1980; 70 in 1990; and nearly 700 wineries in 2020. One contributing growth factor: during the first two decades, some early Willamette Valley wines successfully went head-to-head with the best from France.

Today, we celebrate a major landmark in the region’s history: in 1983, the Willamette Valley American Viticultural Area was established, securing the area’s identity and wines.

Let’s reflect on the dedication and commitment of Oregon’s early adopters; their efforts launched the Oregon wine industry. Let’s acknowledge pivotal events that transformed the Willamette Valley from obscure to a region renowned for the caliber of its product and the cohesiveness of its community.

THE EARLY DAYS

We turned to historian Rich Schmidt, director of archives and resource sharing at Linfield University, where the Oregon Wine History Archive is located.

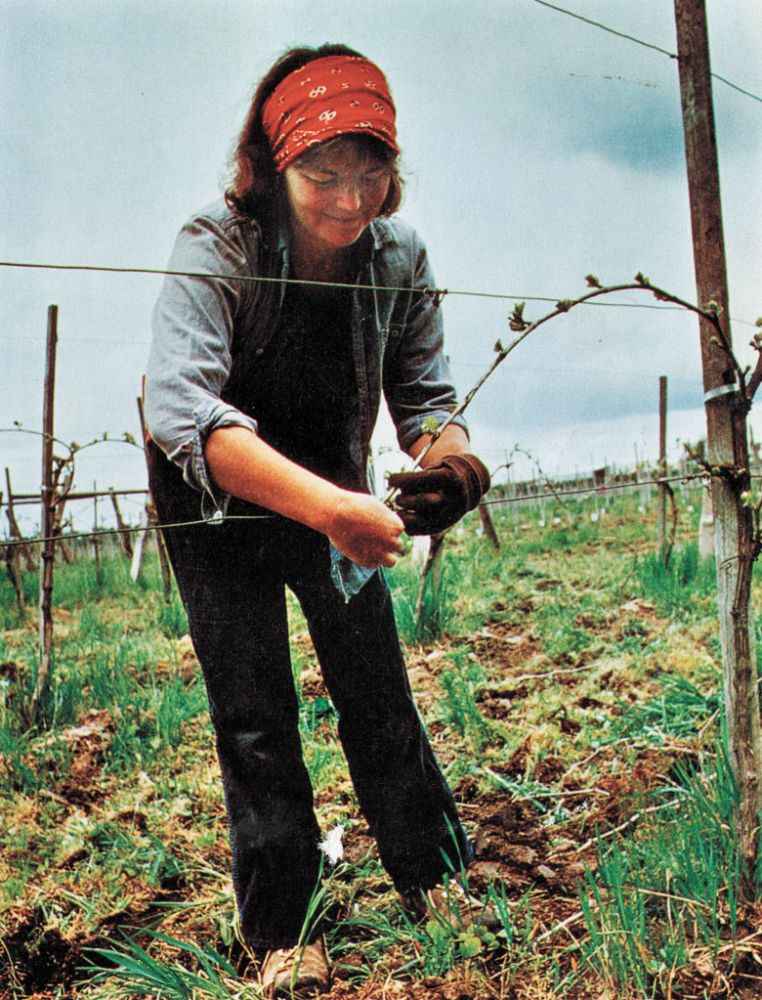

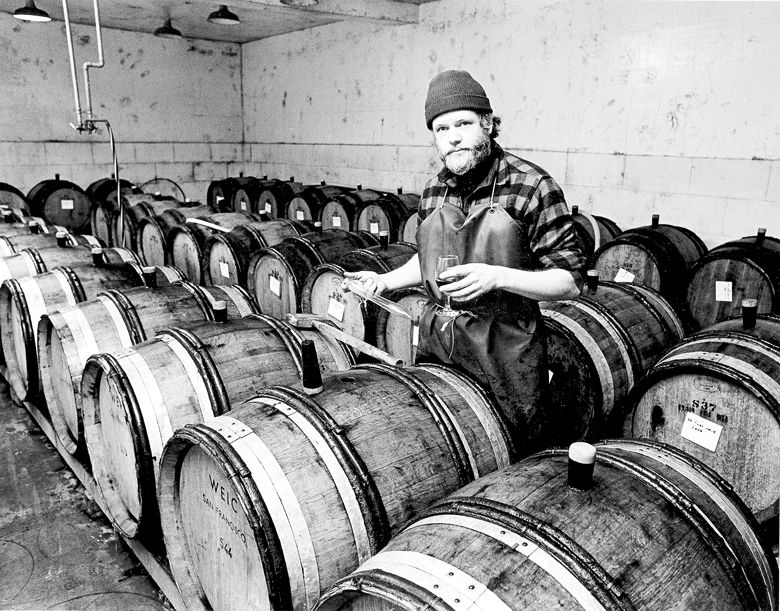

Regarding the initial plantings in the mid-1960s, Schmidt says, “there was sort of a dream of making wine in the Willamette Valley held by a very small number of dedicated and devoted people. They came in the mid, late 1960s and through the 1970s– mostly families with a specific goal of growing Pinot Noir in a cool climate. They believed this was the place to do it and were very passionate. They did a fine job but there wasn’t really any local or international interest. It was a bunch of people with a very small sphere of influence.”

“For the first 15 years, the earliest wineries sold enough wine to stay in business,” says Schmidt, “mostly hand-to-hand sales, and some restaurants took interest.” However, American consumers didn’t possess much wine awareness, or knowledge, and distribution networks were virtually non-existent. “There wasn’t any kind of marketing, tourism or distribution. It was this very nascent thing.”

“One of the most interesting aspects of Oregon’s budding wine industry, specifically in the Willamette Valley, is even when there were only, say, 10 to 20 families making small amounts of wine, they did things like lobbying for land-use legislation to protect current or future vineyard land. They enacted labeling laws far stricter than those mandated at the federal level. That happened during the 1970s, when you could hardly call it an ‘industry.’”

Schmidt applauds the fact that these pioneers had the foresight to recognize that “one of the ways to ensure success in the future was to do these things. Even though everything came at a cost of time, money and energy, yet, they did it anyway. I think it’s a critical phase in our growth.”

COMMUNITY COHESION

Today’s Willamette Valley winemakers speak with gratitude and reverence about the strong, supportive community. Clearly, its roots are anchored in the balance of scrappy independence and mutual support forged in the early days.

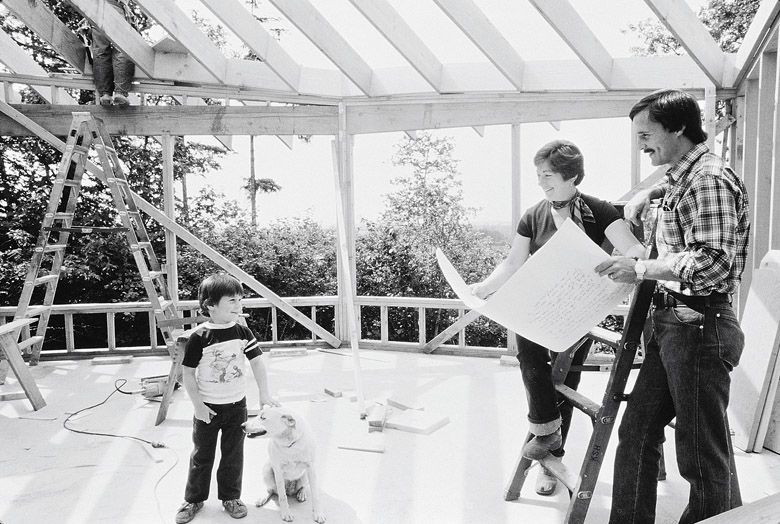

Anna Campbell, creative director at Elk Cove Vineyards, doesn’t recall the early days– she was four when the AVA was granted. However, when she thinks about her parents, Pat and Joe Campbell, founders of Elk Cove, she says, “They were two people who were really, really independent. They wanted to live off the land and do everything themselves. They built their own house out of scrap lumber. And yet they needed to work with the other folks doing the same thing: the Ponzis and Blossers and Letts. They needed community. I think the best part of Willamette Valley wineries is that we’ve managed to hold on to that welcoming vibe and community focus.”

Don Byard, who founded Eola Hills Vineyard and Hidden Springs Winery with wife Carolyn, recalls the collaborative vibe of the era. “We, as the early guys trying to figure out how we’re going to do this, would meet every first Tuesday of the month and talk about growing grapes at the fire hall in Tigard.” A version of that group meets to this day.

THE AVA SYSTEM

Because the American Viticultural Area, or AVA, system was established in 1979, it’s worth noting that other wine regions are also celebrating their 40th anniversary. Prior to the AVA system, no regulations existed governing the content or veracity of wine labels in terms of grape and geographic origin.

“That system of petitioning the federal government for approval of the name and the geographic boundary was set up in response to a European challenge to the sort of Wild-West approach to wine labeling in the U.S.” recalls David Adelsheim, who founded Adelsheim Vineyard in 1971 with his wife Ginny. “The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms came up with this process. As part of it, they made several things contingent on having an American Viticultural Area on your label, but one, especially important to Oregonians at the time, was that the term ‘estate bottled’ was made contingent on the wine having an AVA designated on the label.”

Some may be surprised that the first region granted designation status was the Augusta AVA in Eastern Missouri in June, 1980– the only AVA granted that year. Less astonishing, Napa Valley was number two, one of the seven-out-of-eight California wine regions earning recognition in 1981. When the Willamette Valley became an official AVA on December 1, 1983, it was our nation’s 55th and Oregon’s first.

Willamette Valley winemakers eventually sought even more specificity with labeling, in part because Pinot Noir grapes are so sensitive and reflective of climatic and site conditions. They eventually petitioned for AVA recognition of smaller areas nested within the Willamette Valley. Today, there are 11 AVAs within the designated boundaries of the larger Willamette Valley: Chehalem Mountains, Dundee Hills, Eola-Amity Hills, Laurelwood District, Lower Long Tom, McMinnville, Mount Pisgah, Ribbon Ridge, Tualatin Hills, Van Duzer Corridor and Yamhill-Carlton.

SECURING AVA DESIGNATION

Adelsheim was responsible for the original application process. “I don’t remember who was on the board of the Oregon Wine Growers Association. I don’t remember why they thought I should do it, but I agreed. It was not very complicated in those days. I worked on three, but only two moved forward. They were pretty quickly approved.”

Their goal was “to make it as big as they could, so that anybody growing in what we thought of as the Willamette Valley, i.e., the watershed of the Willamette River, would be included. But it took three or four months of sort of dedicated work, on and off, to come up with the proposed boundaries. I sent it over to the Oregon Wine Growers Association. They looked at it and had no reason to doubt or change it. I sent a typed cover letter to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, and about a year later, it was approved. The only thing in between, they called me and said, ‘What you proposed is really big. Can you make it smaller?’ When I asked what part of the Willamette Valley should we not include in the Willamette Valley AVA? They didn’t have an answer and approved the boundaries we had drawn.”

“I don’t remember a major celebration, in part because the wine industry at that time was much smaller,” reflects Adelsheim. “And we had no idea that this would become the defining system for wine in America, mostly because it’s federal rather than state. We were doing it to solve a very specific problem, as I said earlier, about estate bottling, and ended up with this designation, which is the base designation for wines in the northwestern part of Oregon.”

(At a later date, King Estate Winery, established in 1991, requested that the Siuslaw Valley be included in the Willamette Valley AVA.)

EARNING ACCOLADES

During the 1980s, Willamette Valley wines began earning accolades. Three events in particular have become game-changers in local lore.

“The first big event that people talk about is the Wine Olympics,” says Schmidt. “It was in Burgundy, 1979. Becky Wasserman (a wine importer) submitted a bottle of David Lett’s 1975 South Block Reserve Pinot Noir from The Eyrie Vineyards. As far as I know, she didn’t even tell the family she was entering it. She developed an interest in Oregon wine before almost anybody else did and just happened to have this wine. It placed very highly in the competition. That was the first international recognition of anything that was happening in the Oregon wine industry. The French took notice because this very young wine– it was only four years old at that point– competed with these aged wines from incredibly old, established vineyards and wineries in legendary places within Burgundy… and it did well.”

“That led to a series of competitions comparing Oregon Pinot Noirs with French Burgundies,” continues Schmidt. “The most notable to me is the Burgundy Challenge, in 1985, held in New York City. It considered both the quality of wine, and also the differentiation. Can knowledgeable wine critics, magazine writers, people who know wine, discern the difference between an Oregon and a Burgundian Pinot Noir? None of them could. That was, from my perspective as kind of a wine historian and having spoken to people involved, a huge thing.” This marked the first time that Oregon wine was publicly evaluated and recognized in a larger context. “In this relatively young industry that still didn’t really know what it was doing, didn’t have a grasp on its own terroir or anything like that… to produce these wines is amazing.”

The very successful 1983 vintage “kept many in business and put a lot of people on the map. Then, in 1987, the Drouhin family invested, establishing what is now Domaine Drouhin Oregon in the Dundee Hills. Suddenly, we have the first foreign investment, and not just any foreign investment, but from a legendary Burgundian wine house. That purchased implied: we are impressed by the wines you’re making and believe there’s enough potential to make our own. Having spoken to people who were here, it’s a sort of before-and-after event, to me, of Oregon wine. Those are the milestones in the early days of the Willamette Valley that have set the stage for what came after, for the massive growth of the last 25, 30 years,” observes Schmidt.

THE NEXT 40 YEARS

There’s every reason to predict the Willamette Valley AVA will further reflect the celebrated wine regions of France, continuing to evolve and produce top-caliber wines.

“I definitely have tried to look forward to the next 40 years… and beyond,” says Campbell. “How can we keep this going, not just for the next 40 years, but for the next 400 years? I think there’s a lot that we can do together. How can Willamette Valley wineries team up in the future? I think we’ve done a lot to address environmental and social sustainability issues by forming ¡Salud! and developing environmental designations like LIVE and Salmon Safe. I think that with more of us now, we have even more potential. Our new generations are going to come up with even more ways to band together and do our part to help our communities. It’s an exciting time. We have a lot of newcomers and others interested in the Willamette Valley as a growing region. I think we’ve become an even more welcoming place, and I look forward to seeing what all that new energy brings.”