Bewitching Tales

Multi-award-winning Canadian author’s memoir

By Neal D. Hulkower

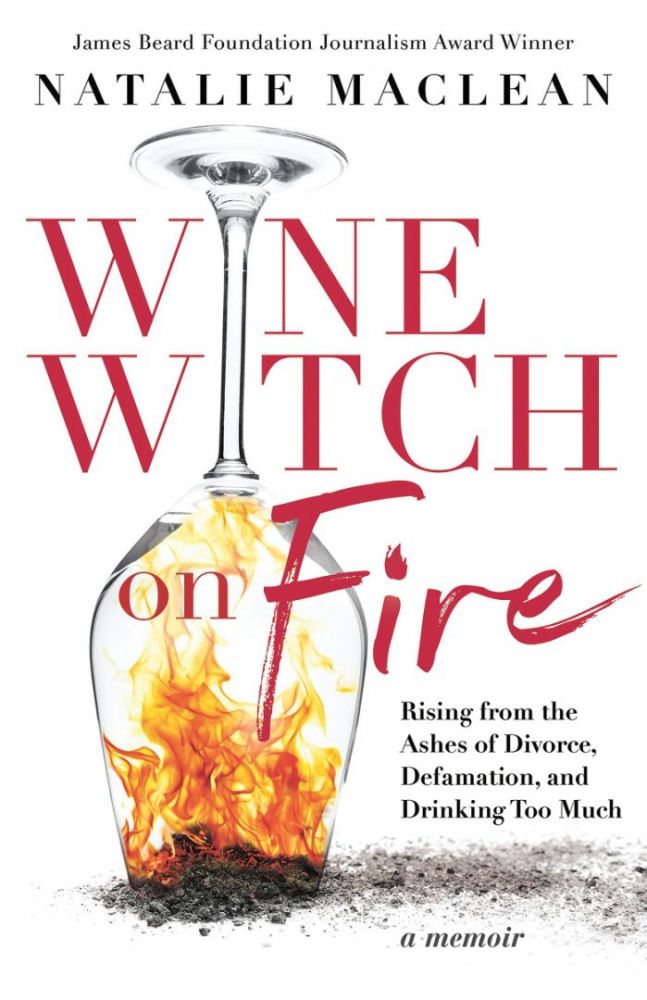

“When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions,” laments King Claudius in Act IV, Scene V of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. In 2012, Natalie MacLean, multi-award-winning Canadian author and chief of wine happiness at nataliemaclean.com, experienced this fact personally. She tells her tale in Wine Witch on Fire: Rising from the Ashes of Divorce, Defamation, and Drinking Too Much available on Kindle May 9, and the paperback edition June 6.

The memoir describes events from the time the first sorrow struck in January 2012 to MacLean’s emergence from her trio of woes in December of 2013, with numerous flashbacks. The section titles reflect the phases of a vineyard’s annual growing cycle, an appropriate, though obvious structure for a wine personality’s story. Each segment contains two to eight chapters describing her traumas and reactions, as well as digressions from her past.

“Begin at the Season’s End” details the accusations of intellectual and content theft, along with copyright infringement, made against MacLean. These appeared on December 15, 2012, in an article on the Palate Press website, authored by six wine journalists. At the time, she was experiencing a particularly stressful year: her husband of 20 years left their marriage and MacLean increased her recreational wine consumption to numb the pain. MacLean holds her readers in suspense because they must wait until the last two sections to learn the details of the looming catastrophe and its resolution.

“Back to the Season’s Roots” is the account of her husband choosing to leave with no warning after two decades of marriage– her first sorrow. It includes the story of a repulsive assault MacLean endured during a sales conference while working at a computer company. She also describes her preparation for and transition to professional wine writing is also described.

“Budbreak” continues the narration of separation and divorce. Stressed out MacLean over-consumes “personal wine,” in contrast to the “work wine” which she automatically spat out, and suffers the effects: her second sorrow.

“Pruning” and “Harvest” intersperse anecdotes about MacLean’s gradual recovery from the two sorrows with flashbacks of her childhood and university years. She cites several examples of manifest sexism in the male-dominated wine industry, along with her return to dating and the beginning of what continues as a long-term relationship.

“Wildfire” and “A New Season’s Growth” expand the attack on MacLean’s professional integrity– the third sorrow– introduced in the initial section. If made to stick, the allegations would likely terminate her wine-writing career instantly and with extreme prejudice. They didn’t. But until the situation was resolved, MacLean became the subject of shunning, online shaming, ugly misogynistic and sexist disparagement. Although a few in the wine writing community did rally to her defense.

What was the exact nature of the alleged crime provoking this outrageous behavior? In addition to posting her own tasting notes on her website, MacLean had included in a separate section brief excerpts from reviews of other professional wine writers. She identified the writers with initials spelled out in a separate directory following the example of some of the print and online publications of the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, or LCBO. But the comments were credited to LCBO’s Vintages Wine Catalogue, where they first appeared. LCBO posted reviews of many writers, including MacLean, never requesting permission. “I assumed the reviews must be in the public domain as they were posted on a government site,” she admits. Though she believed that she was doing nothing different from what others had, she no longer does so. Lawyers confirmed neither copyright violations nor intellectual property theft. Despite her mea culpas and no longer including reviews of others, resentment and attacks took time to die down.

MacLean’s prose is so emotionally vivid, even this not particularly touchy-feely old guy felt her anguish and frustration. On the other hand, sometimes she offers what could appear as too much information depending on the reader’s threshold for such things. Laugh-out-loud humor, brilliant wit, clever phraseology and alliteration dispersed throughout leaven the sadness and illustrate her path to reemergence from the darkness.

In general, I found the witch metaphor woven through the text surprisingly effective. In the Author’s Note, MacLean explains: “Witches resonate with me because their strength comes from within, not from external validation. They also embody the unity of women, the power of the feminine and the healing connection to nature.” While, perhaps overly dramatic, she compares her treatment by detractors to what witches endured in the past.

Unlike her previous two books, wine assumes a supporting role in the story, as opposed to being the star. Nevertheless, specific bottles are mentioned throughout, along with some background on wineries and winemakers.

Surviving divorce and reversing the descent into excess wine consumption, while laudable achievements, are frequently not worthy of being memorialized in a book. But the addition of her account of the career-threatening accusations, their impact and, especially, what they reveal about the industry, as well as her emergence, makes for a compelling read. MacLean powered through her trilogy of tsuris and seems to have emerged stronger and wiser.

Despite the passage of more than a decade, her acknowledgment of issues and subsequent rectification of her approach to posting wine reviews, I recently learned that hostile feelings endure in at least one influential group in the wine writing world. Fortunately for MacLean, this residual resentment seems not to have affected her career adversely.

Ever the marketer, MacLean provides “A Bewitching Wine Guide For Book Clubs, Wine Groups, Moon Covens, and Readers of Wine Witch on Fire,” which can be downloaded gratis. It includes a recommendation for a Nasty Woman Persistent Pinot Gris from Oregon, among other bottlings.

Though this book might be viewed as simply another example of MeToo-era chick lit, it is far more. As a male beyond a certain age, I see it as another important reminder that bad things are still happening to good women– sometimes by otherwise good people countenanced by other good people. The impact remains as virulent as when the perpetrator is a sociopath, such as described by Victoria James in Wine Girl: The Obstacles, Humiliations, and Triumphs of America’s Youngest Sommelier. In any case, this behavior must stop. MacLean’s memoir raises the possibility of that happening sooner.