A Tale Divine

How grapevines may have arrived in the Pacific Northwest

By A.R. Fitzhugh

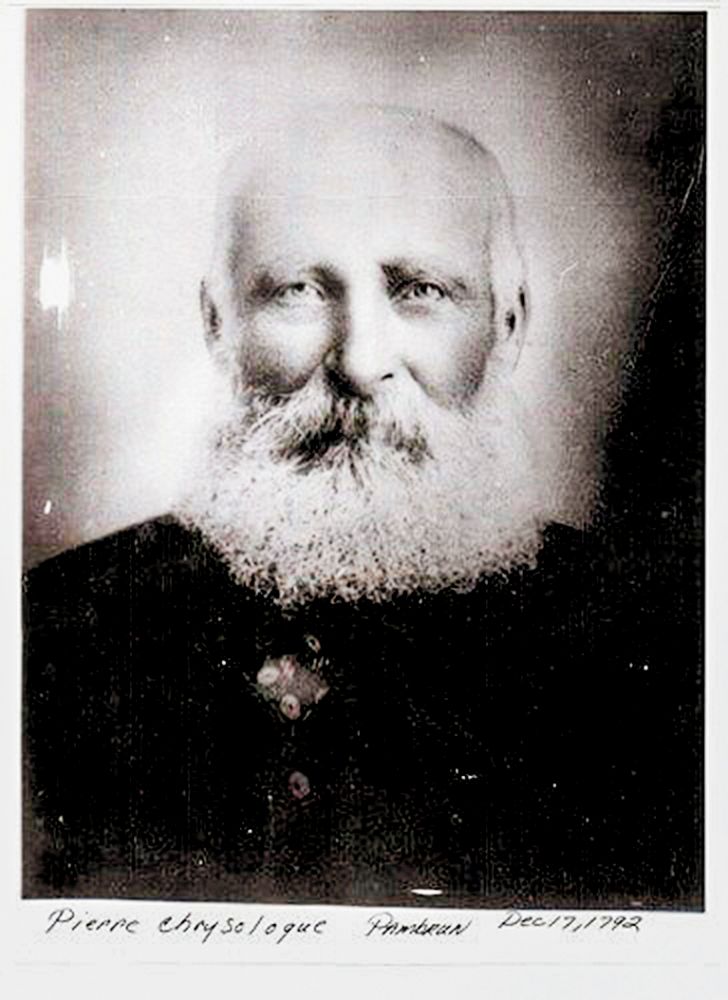

The cultivation of the first grapevine in the Pacific Northwest represents a colorful piece of regional lore intriguing to Jim Bernau, founder and CEO of Willamette Valley Vineyards. Not only is it a foundational tale for the robust industry that has been his life’s work, but also a family story handed down for generations, connecting him to his fourth great-grandfather, “a dapper little fellow” named Pierre-Chrysologue Pambrun.

Recently, Bernau asked if I would research the story as a historian to determine its degree of authenticity. This endeavor sent me on a journey between The Oregon Historical Society’s downtown Portland research library and a remote farmstead in Umatilla County, where I met the venerable Sam Pambrun, teller of tales and keeper of family lore. Sam has spent most of his life compiling stories of his ancestors’ activities in the region. He was kind enough to share the oral traditions about Pierre and the grapevine given to him.

Although sources differ slightly, the story goes something like this: On a rainy night in March of 1826, at a London dinner party, Royal Navy Lieutenant Aemilius Simpson was celebrating his imminent departure on a voyage to the “backside of America” and the far-flung Oregon Country. The 34-year-old Napoleonic Wars veteran had been enlisted by the Hudson’s Bay Company, or HBC, as a surveyor and hydrographer in their Columbia District. The exciting opportunity had been made possible by his half-cousin, the eminent George Simpson, governor of the HBC’s operations in North America. The two men would soon depart England on a ship bound for New York, but not before enjoying a fine, farewell feast with friends and family.

According to legend, during dessert an anonymous female guest, well-satiated with food and drink, playfully extracted seeds from a grape and an apple, placing them in Aemilius’ pocket for planting at his far-off destination. Another version claims it was actually several women who, “in the spirit of merriment,” gave seeds to all the men at the table. It might also have been Aemilius who put the seeds in his pocket. In 1836, doomed pioneer and missionary Narcissa Whitman recounted the story, stating that “a gentleman … while at a party in London put the seeds of the grapes & apples, he eat [sic] in his vest pocket…” Whatever the case may be, the seeds were quickly forgotten in the haste of Aemilius’ departure. Eight months later, shortly after he arrived at Fort Vancouver, they were rediscovered.

At this point, Bernau’s ancestor enters the story. Like Aemilius Simpson, Pierre-Chrysologue Pambrun also recently arrived at Fort Vancouver. The energetic, 33-year-old clerk for the Hudson’s Bay Company had led an eventful life. Born along the banks of the St. Lawrence River in southern Quebec, Pierre had served with distinction during the War of 1812 as a member of light infantry unit, the Canadian Voltigeurs, earning a promotion for his actions at the pivotal Battle of Châteauguay. After the unit disbanded, he began his service with the HBC and ordered immediately into the Pemmican War against the rival North West Company, or NWC. In 1816, Pierre, taken hostage, subsequently witnessed a series of ravages committed by the NWC, including the Seven Oaks Massacre. Upon his release, he spent a few years testifying about his experience.

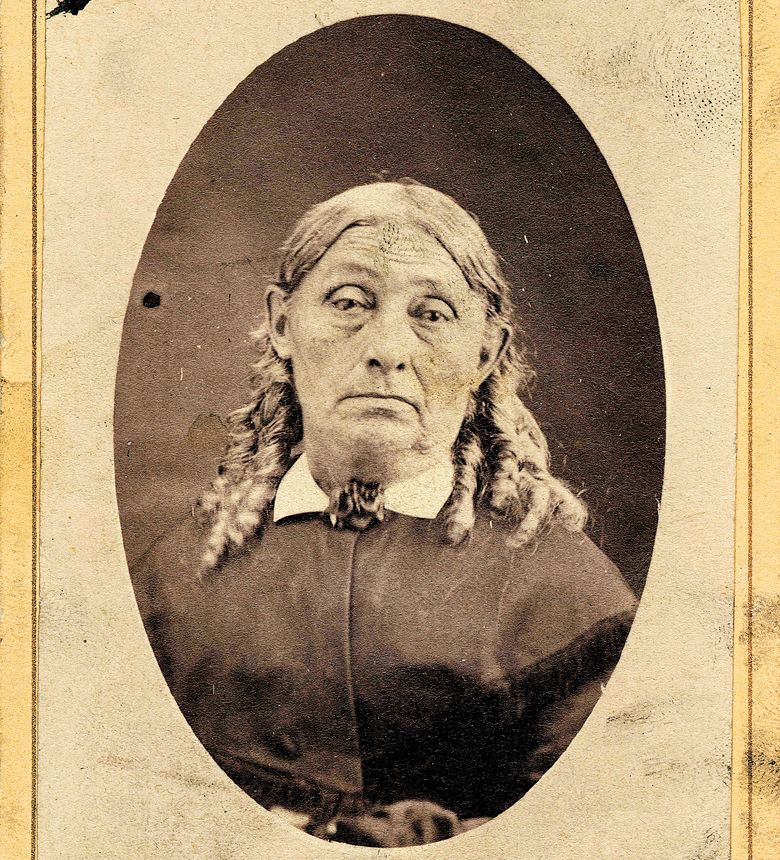

In 1820, Pierre was transferred to Cumberland House in northeast Saskatchewan, and soon met 15-year-old Catherine “Kitty” Umfreville, the Métis daughter of a prominent Hudson’s Bay Company family. On January 10, 1821, Pierre and Kitty were joined together in what was known in fur trade society as a mariage à la façon du pays, or country marriage. While this centuries-old rite has often been considered a practical, socioeconomic institution, historian Sylvia Van Kirk rightly notes that many of these common-law marriages developed into loving and lasting unions. This was certainly the case with Pierre and Kitty. Seventeen years after the first wedding, they married again in a Catholic ceremony at Fort Vancouver with their many children in attendance.

Not long after they were wed (the first time), the young couple slowly began moving west as they transferred from post to post. Eventually, they settled in the New Caledonia district of modern-day British Columbia, where Pierre worked as a clerk at Fort Kilmaurs and Fort St. James. In the spring of 1826, he traveled south to the recently established Fort Vancouver as part of the New Caledonia fur brigade. While some discrepancy exists in the sources about the length of Pierre’s stay at the fort, he was most certainly there when Aemilius arrived November 2, 1826, after an epic, 2,800-mile trek across North America.

To welcome the new arrival, the fort’s chief factor, Dr. John McLoughlin, hosted a dinner party. It was at this event that Aemilius, wearing the waistcoat he last wore in London, reportedly rediscovered the apple and grape seeds in his pocket. After hearing the charming tale of how they got there, McLoughlin and Pierre decided to plant the seeds during the winter in little glass boxes behind a stove. According to Pambrun family tradition, Pierre had the necessary experience from farming at his various posts over the years. However, family historian Sam Pambrun also believes the fort’s head gardener, William “Billy” Bruce, was likely involved.

When the seedlings were large enough to plant outdoors, McLoughlin’s daughter, Eloisa, recalls that her father “used to watch the garden so that no one should touch them.” In August of 1828, less than two years after Aemilius remembered the seeds in his pocket, fur trapper Jedediah Smith visited the fort and remarked that “some small apple trees and grape vines” were growing. A year later, in 1829, a missionary in Hawaii wrote a letter to his superiors about a conversation he had with a “Captain [Aemilius] Simpson,” who was conducting business for the HBC. According to the missionary, in their conversation, Aemilius had extolled the agricultural virtues of Fort Vancouver, stating “he planted the grape and the apple at that place, and they appear to be flourishing.” By the time Narcissa Whitman arrived at the fort in 1836, the apple trees and grape vines had “greatly multiplied.”

Whether or not the grapes were ever used to make wine is unclear. However, while some historians have dismissed the idea outright, as there are records of wine being shipped in from London, I believe it is likely they at least tried. In his conversation with the missionary, Aemilius had also stated how the residents of Fort Vancouver “cultivate barley, malt it and make beer which they will soon be able to export in small quantity.” While not wine— the vines from his seeds were still too young at this point— it indicates there was a desire for that type of industry.

Jump ahead twelve years to 1841: a visitor to the fort was told the grapes “had succeeded well but of late years their cultivation had been neglected.” Why they were neglected is never revealed, and there are a number of possibilities, but it implies their original purpose had been much more than simply providing for the fort. A couple of the grapevines were eventually planted in front of McLoughlin’s “big house.” Over the years they wound their way up and around the veranda, becoming one of Fort Vancouver’s most celebrated features. Visitors often commented on the “fine grape vines loaded with fruit,” and it was well known that McLoughlin and others would give cuttings to immigrants who asked.

In 1832, Pierre was promoted to the chief clerk at Fort Walla Walla. He almost certainly carried some cuttings from Fort Vancouver. The two gardens he and Kitty built utilized irrigation, the first of their kind in the region. Narcissa Whitman described them as “verdant,” identifying crops including melons, potatoes and corn.

Sam Pambrun believes that both likely had orchards, perhaps even a vineyard. Over the next decade, Pierre excelled in his position at the challenging and strategically pivotal location. There are dozens of accounts from those who visited during his tenure; almost all mention his warmth and compassion. Tragically, on May 15, 1841, Pierre died from injuries he suffered in a horse-riding accident on the way to his gardens, leaving behind his beloved Kitty and their nine children. He was buried at Fort Walla Walla and later reinterred at Fort Vancouver. Kitty would join him many years afterward on September 18, 1886.

Today, 181 years after his death, Pierre’s legacy of hospitality remains a driving force for Jim Bernau and Willamette Valley Vineyards.