Secret’s Out at Abacela

By Hilary Berg, OWP Editor

If you ever have a secret you simply must tell someone, Earl Jones of Abacela is your man. Trust me, your secret will be safe.

You see, Earl and his wife, Hilda, have been keeping a secret since before they arrived in Oregon in 1994, when they bought property in Roseburg for the sole purpose of planting Tempranillo — the famed grape of the Rioja and Ribera del Duero regions of Spain.

Of course, it’s no secret they planted Tempranillo in what they named Fault Line Vineyard, and that they’ve been bottling it — and winning many awards — since 1997. Nevertheless, the big secret does have to do with their estate fruit.

Earl and Hilda announced their news to an intimate group, this writer included, in the Havana Room at ¡Oba! in downtown Portland, on Thursday, Sept. 29.

“[We] have been involved in what seems like a lifelong project: to make a different kind of wine that hasn’t been made in this country,” Earl said.

“Making this wine was our intent when we moved to Oregon. We had traveled in Europe and had tasted a lot of wines both here and there,” Earl continued. “We enjoyed the structure of Spain’s hierarchical top, the Gran Reservas, but we had some objections. Just like an art critic doesn’t have to like Michelangelo’s finest, we didn’t exactly like some of the wine’s attributes, so we thought we could make a better one. And that’s what we think we have in the bottle.”

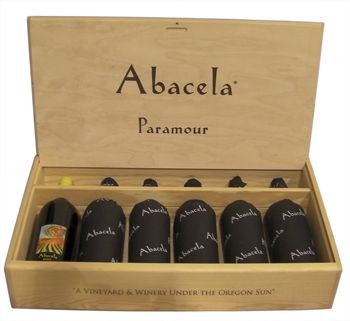

The bottle Earl is referring to is Paramour, a 2005 proprietary, estate-grown Tempranillo blend inspired by Spain’s celebrated Gran Reservas.

To be considered a Gran Reserva in Spain, law requires the wine spend two years in oak and three years in bottle. Earl followed Old World rules but tweaked a few practices to suit their style and, in their eyes, improve the wine.

Earl wanted French oak instead of American. He didn’t like the fact that American oak masked the fruit. He also didn’t care for the low level of extract in many of Spain’s Grand Reservas; he wanted more extract, more concentration.

“The winemaking of Gran Reservas has changed over the years. It seems we were not the only ones critical of the contents of the wines.”

Earl and Hilda have carefully appraised every vintage since 1997, looking for perfect conditions for the making of their first Gran Reserva-style wine. After eight years, 2005 seemed to have all the right ingredients, especially quality and quantity.

When Earl started making wine in the mid-’90s, he had never made a glass of wine before. “I just understood the words I had read.” After accumulating experience, he began to better understand Tempranillo. He experimented with blending and nurtured his estate vineyard through its early years.

“By 2005, we had tasted enough Tempranillo and had seen it age — and same with the other varietals — to put this wine together,” Earl said. “I personally could not have done it before 2003 or 2004; the vineyard needed that time.”

Earl sensed they had the possibility of making Paramour on the crush pad. “Since Tempranillo is the core of this wine, we had to have great Tempranillo, and we did.”

But it wasn’t until springtime, when malolactic fermentation was complete and it was time for its first racking, that Earl was certain the wine was going to be Gran Reserva quality. “It had better acidity than the 2000 vintage, which was a stellar vintage. So he thought, “Yeah, this might be the year.”

For the blend, they selected the very best barrels of the finest block of Tempranillo — the rest went into a Reserve Tempranillo that received high marks. They then picked the best barrels of the other blend components, which also earned their own individual awards.

After making the desired blend, Earl adjusted oak — average age of barrels was 1.7 years — to suit his palate and adjusted it again at around 18 months. In all, it spent two years in oak and four in bottle, hidden from passersby. Although it’s only five years before a traditional Gran Reserva can be released, Paramour took six. Earl said it needed the extra time in bottle.

“It has shed its baby fat and is beginning to express the structure, balance and beauty that we made it for,” Earl said.

The wine was released Oct. 15, six years to the day it was picked. Although Spanish Gran Reservas are spendy, Abacela will sell Paramour for $90 a bottle.

A majority, about 75 percent, of the 170-case production will be offered to the winery’s loyal wine club; the rest will be available at fine restaurants and wine shops, each with a very small allocation.

If you happen to get your hands on a bottle, don’t open it, but rather lay it down for at least ten years or more. As one of the tasters in the small group at ¡Oba! pointed out, “This is a collector’s wine that will cross generations.”

But don’t worry if you can’t find a bottle. Abacela has the next batch already in barrel. As for which vintage made the cut this time around, Earl’s not saying. As you can see, the secret is definitely safe with him.