Talha Wine Tales

Clay vessels and Portuguese wines

By Neal D. Hulkower

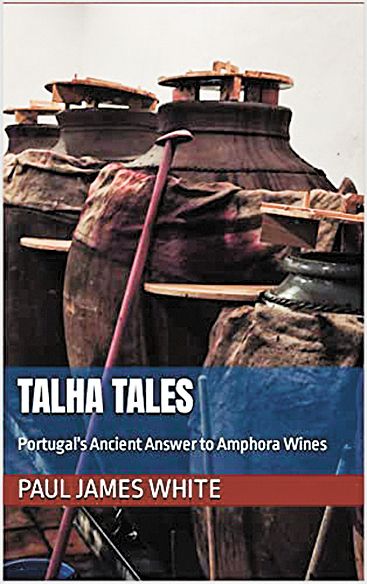

Paul James White intends to set the record straight: The expat-American, who spends time in Oregon, as well London, Languedoc and New Zealand, he wrote Talha Tales: Portugal’s Ancient Answer to Amphora Wines. His enlightening book begins with what is likely to be an unsuccessful exhortation to correct the usage of a word, “amphora.” Amphoras, two-handled clay pots, he reminds us, “were used EXCLUSIVELY for transportation, NOT FERMENTATION [emphasis his].” Instead, “[t]he correct name for these pots are Roman dolia, Georgian qvevri, Armenian karas, Spanish tinajas, or Portuguese talha.” Nevertheless, he admits “amphora” likely won’t be replaced by the more accurate “terracotta” or “clay pot” to describe the ancient fermentation vessel regaining prominence. In Oregon, Andrew Beckham, ceramics artist and winemaker, has embraced this method, along with the “a” word, for his A. D. Beckham label, featuring wines fermented in clay vessels he fashions by hand.

Despite assigning this language lesson top billing, White is on a much more important mission. He’s shining a spotlight on a little-known, but really old wine region, in a country best known for its fortified dessert wines. His masterful book is divided into three parts: For the Oenophile, The Producers, and For the Wine Tourists, the latter written by his wife, Jennifer Mortimer. They are subdivided into a total of 33 short chapters and generously illustrated with color photographs. Part I “is full of background and esoteric geeky wine and cultural stuff I love as a former historian,” White explains. The contents of the others should be obvious from the titles. Following these are Bibliographic References and a Glossary of Terms, essential for deciphering Portuguese words like adega, meaning winery, not always translated in the text at first use.

Part I includes information crucial to understanding what follows and needs study, lest the reader be left without context, despite White’s invitation to “pick and choose what [the reader] find[s] useful.” Like your best history teacher, White’s conversational tone tells the story of grape growing and winemaking. In Alentejo, the region comprises eight divisions. Less than 100 miles from Portugal’s capital, Lisbon, it fans out eastward toward the border with Spain.

Possibly as far back as the Phoenicians, but certainly during the Roman occupation of Lusitania (as Portugal was called at the time), wine was made in clay vessels. While evidence exists that the Republic of Georgia made wine 8,000 years ago in similar containers called qvevris, long before Portugal, there is one important difference. A qvevri is buried so the wine must be extracted from the opening at the top, while a talha sits above ground and has a hole at the bottom through which the wine is drained. White includes an extensive discussion of the benefits of the talha over the qvevri, especially temperature control through evaporation. Both designs allow natural convection currents to stir the lees, thereby adding texture. He asserts, “Every talha is a terroir unto itself.” In fact, the same can be said of every type of clay vessel used for winemaking.

As in Georgia, what goes into clay pots, made in a range of sizes, are primarily white, indigenous grapes. Later, some red grapes and international varieties were added, likely to satisfy outsiders’ palates. Also, both regions have embraced other winemaking technologies, like concrete eggs, oak barrels and stainless-steel tanks. Clay barrels produced in the 1800s are still being used in one winery in Alentejo. These two areas also bottle wines after a period of aging in clay or other vessels.

White shares the knowledge about talhas, which he calls “[t]he world’s most perfect machine for making wine,” and the culture evolved from them he learned during frequent visits to Alentejo over the last dozen years. After centuries of use by the Romans, likely followed by monasteries making wine for religious purposes, secular production began to flourish in the 17th century. Over time, families and small cafés called tascas, represented the only places wine was made in talhas. Traditionally, grapes were harvested and crushed, then placed in the clay vessels to ferment until St. Martin’s Day, November 11. Afterward, the young wine was drawn from the hole on the bottom. The talha, typically empty by March, likely limited oxidation but also leaving thirsty folks to wait until the next harvest for something vinous to drink.

Small-scale wine production in Alentejo diminished, in part, because of bottling, which arrived in the 1970s, allowing year-round wine consumption. “When I first began searching out talha-made wines back around 2010, and finally tasted some in 2012, few tascas and family producers were still active, another handful of professional winemakers focused on Alentejo’s relatively new Vinho de Talha DOC designation, and one quixotic attempt to resurrect factory scale production,” recounts White. Since then, the situation completely changed direction, evidenced by the stories that follow.

Part two features detailed descriptions of 17 producers of talha wines, ranging from small family-owned wineries producing a few thousand bottles, to the largest, making over 133,000 bottles annually. For those planning a trip to Portugal, complete contact information is provided. Some are new; others have histories dating from the early twentieth century. Since the last pot-makers shut in the 1920s, with new ones only recently emerging, wineries have refurbished older talhas, some from the 17th century, and using them in production.

White concludes each chapter with extensive tasting notes, many with scores. Of particular value are verticals and those for multiple samplings of the same wine over time. He awarded 100 points to the 2015 Herdade do Rocim Jupiter, a wine that sold for €1000, the most expensive Portuguese wine, and the costliest clay-made wine ever. Writes White: “On all counts this is a wonderfully complete wine, made from an old field-blend vineyard that has offered up a rich mix of red and black fruit aromas and flavors, harmoniously bleeding into one another, further enriched by a graphite mineral gloss. Highly polished and as slick as it is smooth, all that underpinned with a complex layering of tannins. Pure, plush, concentrated, explosive, mouthfillingly complex… it all leads onward towards a long, perfectly tapered, decrescendo that fittingly plays out with more than ample residual flavors. A pitch perfect wine.”

No wonder it sold out in a few days.

Although I didn’t recognize any of the producers, White’s descriptions aroused my interest. Now I will be looking out for these talha-made wines.

After inspiring interest in Alentejo’s history and renaissance, while tantalizing readers’ palates with colorful descriptions of the wines, White leaves it to Mortimer to provide a travel guide to the region. Though brief, Part three contains everything necessary to visit. Various levels of accommodation are listed, along with restaurants and a handful of towns and sights of note. “The best time to go…is St. Martin’s Day…Then you may have the absolutely finest talha experience, rambling the back alleys of the talha villages seeking the festive opening of the talha…” advises Mortimer. For the virtual tourist, she includes three recipes for Alentejan dishes.

As good as this book is, a second edition should be issued within a few years. White posed and pondered many questions. Some he left unanswered, and one, relating to lack of evidence of clay pot use between Roman times and the 1600s, was resolved moments before going to press. In addition to editing some misspellings and typos, removing duplicate tasting notes, and thoroughly proofing the text, information about the history of talhas, some of which is still being unearthed, can be confirmed and incorporated. Many of the wines White described were in their infancy. It would be instructive to discover how they evolve. Since Alentejo has become more popular, I welcome an update on its dynamic environment.

The reascendance of Alentejo’s ancient vinification process stands as one of the most exciting underreported events in the wine world during the past decade. As White frequently traveled to the area during its renaissance, he could chronicle the changes as they unfolded. His authoritative, yet eminently readable love story to Portugal’s clay fermentation vessel illuminates an exciting and unfamiliar wine region that should interest every adventurous wine lover eager to explore something different.