Weather, Climate and Wine: It's All A Front

Weather terms explained

By DR. GREG JONES

El Niño, La Niña, PDO, atmospheric rivers, bomb cyclones… what do they mean and how do they effect viticulture?

All these terms describe aspects of global to regional weather and climate phenomena. While they have seemingly sprung into our vernacular of late, each of these weather and climate drivers has been with us for millennia.

The naming and categorizing of weather and climate events have been generated by both scientists and the media to better describe them and bring more awareness to the public. But often, there is confusion about their meaning and how they affect us.

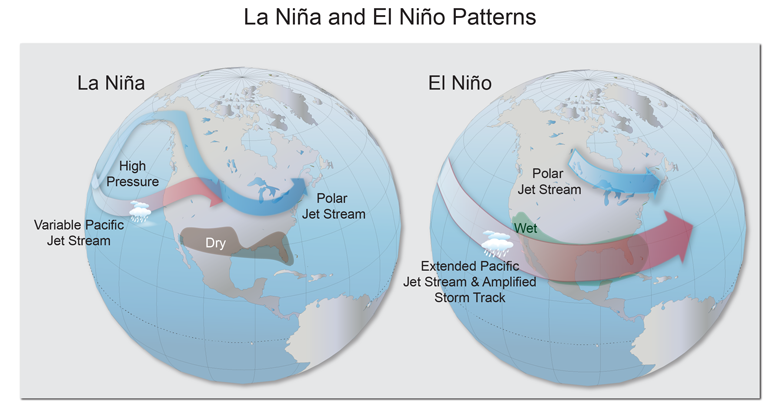

The terms El Niño and La Niña originated from the study of what is called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO as it is known in climate science. ENSO categorizes the weather across the tropical Pacific Ocean produced from variations in the circulation of the trade winds and sea surface temperatures from South America to Oceania. Interestingly, it was originally observed by a British scientist examining the failure of Indian Ocean monsoons, which caused severe famine and the periodic collapse of the tea industry in India. El Niño and La Niña represents the two main states of warmer than normal and colder than normal ocean temperatures in the tropical Pacific, respectively.

The term Pacific Decadal Oscillation, or PDO, arose from the study of salmon runs in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. Scientists discovered when the number of salmon were up in one region, they were down in the other. The PDO primarily describes the shifting ocean temperatures in the middle of the North Pacific compared to those along the North American coast. Like El Niño and La Niña, the PDO has a negative phase, with waters offshore colder than average, and a positive period where they are warmer than average.

Atmospheric rivers have been in the news lately, with California receiving more than its fair share this winter. Atmospheric rivers are large paths of moisture that occur as low-pressure areas over the Pacific Ocean pull air with large amounts of water vapor toward the continent. In the western U.S., they have also been called “pineapple express,” as they appear to transport moisture directly from Hawaii to the Mainland. However, they are not unique to our region, occurring along west coasts of continents where air moves off the ocean onto the land.

Bomb cyclones are storms typically forming in winter when a midlatitude cyclone or low-pressure area undergoes “rapid intensification” as the atmospheric pressure drops quickly. Often associated with high wind speeds and heavy precipitation, they carry the potential for significant damage.

Each of these weather and climate phenomena interconnects in various ways. For example, in El Niño periods, atmospheric rivers tend to be more common and contain more moisture than during La Niña periods. During the negative PDO phase, bomb cyclones often occur more frequently along the West Coast. But, like most things in nature, these relationships do not hold consistently.

How do all these phenomena affect the growing of grapes for wine production? First, they occur mostly from fall through winter and into spring but can still influence aspects of the growing season. For example, ENSO and PDO produce spatial and seasonal variations in temperature and precipitation, resulting in differences in the severity of winter cold events, snowpack accumulation, spring frost and drought. And, as this winter and spring has demonstrated to California, atmospheric rivers and bomb cyclones can bring extreme precipitation, flooding, and damaging winds, but also drought-busting amounts of snow and rain.

Year after year, Oregon’s climate contributes to our celebrated vintage variation. Weather, Climate and Wine explains how the weather affects our grapevines, fruit and, ultimately, wines. Visit www.climateofwine.com to read more in-depth reports.