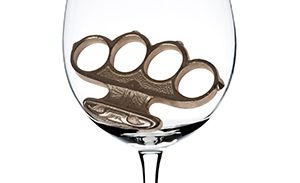

Brass Knuckles

Or how to really look at a glass of wine

By Ken Friedenreich

"The mystery of art is that there’s more than you put down.”

(“A Pimp’s Revenge,” by Bernard Malamud)

In the summer of 1960, the Houston Contemporary Arts Council presented “The Ugly Show.” It was an exhibit of art by another name — detritus from the bayou at the time was snaking through metropolitan Houston, when big hats meant something. The program catalog was written by Donald Barthelme, who was, at this time, establishing himself as a writer of infuriatingly bizarre short stories. Many of them, as he refined his style, were also pants-wetting funny. This exhibit was right up his alley.

“The Ugly Show” was making a point. A galloping horse may look nice near the gun cabinet in the den, but what of a rusted mattress spring hauled from the Dickensian mire and stood on one corner in Texas wildflower light?

Or, perhaps, a set of brass knuckles.

They were mounted on a dissonant background, at least for an implement of connected rings used to break the jaws of street punks or transporters of contraband. Taken from its accepted functional context, the brass knuckles suggested anthropomorphic elegance, like a series of wedding bands or a device to help aspiring concert pianists play block chords with even pressure.

The everyday meaning and purpose and representation of objects, the show and its catalog tour guide seemed to say, “Look at these knuckles a different way, Pardner.”

Now you know why it’s a bad idea to drink wine from a gimme-cup sporting a team logo. The cup not only changes the context, it steals it. What gazing into a nice stem of wine will do is the first rung on the ladder to Wine Parnassus — or, less flamboyantly, to wine enjoyment.

White wines — Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, Sauvignon Blanc, Riesling — can show the shimmer of gold, pale yellow, platinum gold or even meadow straw. Each reflects an aspect of sunlight without whose Empyrean gaze no grapes would grow and ripen or, with the vintners’ magic, show up in the stem at all.

Color anticipates and the sparkle fires not only our visual senses, but all the others — we can anticipate the aroma of citrus or tropical fruit; we sense the cool of the sip in our mouths, we can taste the tangy acidity, or the oaky roundness or the vanillin hit-and-run effect; we can store an impression of transient springtime in the lingering finish. We start with a toast or the clinking of glasses. Thus, our remaining sense of hearing is also engaged.

This happens before we sip the wine because visuals call forth memory. The colors tell a tale, like a prologue, all to tease, “You ain’t seen nothing yet.” But alas, we have, if we patiently regard the visualization of the wine as an experience itself.

A rosé wine appears from pale pink of the white Zin — the 7-Up of beverages with an age restriction — to more colorations, even pallid ruby and rose captured in the light of Manet or Pissarro’s imaginings. The hues of rosé contain subtleties other wines do not care to infer. We rightly associate the blush of these cheeks with the summer patio, but neither allows the calendar or the produce in season to deter your considerations.

The blush rush also calls to mind sparkling wine. A sparkling wine — pink, red or golden yellow — will talk to you in fizzy dialect, adding a soundtrack to the visual. Indeed, one imagines Titanic diners cheering one another’s good fortune through the lights cast by their rose colored-stemware, failing to notice that the ice isn’t in the bucket but dead on course. Fizz adds fun and prickly resonance to that sparkle, and the flute encourages the bubbles to soar mouth-ward. Damn those half-frozen torpedoes! We’re enjoying this dance.

Red wines show their colors another way. They can look like red satin with sensuous folds holding something back, or they can look imperially ruby purple and defy looking through the contents. All wines capture light, but the wine refracts the light illuminating what the glass contains. Better seeing wine empowers us to see better all things.

Properly aged and stored wines sometimes lose their brightness in the stem. “All that glistens,” may be gold in a Chardonnay, but over time, the striking aspect can diminish into a pallid yellow. Reds, in particular, of library quality can appear to have a hint of brown or earth tone at the surface of the wine in the glass. What such wines give up in bright fruit of youth trades off with complexity and subtle structures in aged wine; it’s like becoming wise over time when once you were just clever. Linguistically, “brown” sounds a pejorative note; however, unless a wine is corked or cooked—the left in your trunk bit—the alteration of color ought not deter you.

Two instances from the neighborhood suffice: several years ago I enjoyed a remarkable reserve Chardonnay from The Eyrie Vineyards produced in President Reagan’s last year in office. It was beautifully made and what its color lacked in brilliance was more than compensated for by its complexity and scrupulous balance. A later pre-millenial Pinot Noir from Raptor Ridge proved that our most famous finicky varietal can lose a little hue and gain more than a semblance of classic character.

If you pop a cork, pour a draught, chug it down—well, that’s like using brass knuckles to break a jaw or at least, as we say in polite society, focus another’s attention on the intent of our communication. Even a humble jug wine will want to express itself visually. So give it a chance, not a concussion.

Winemaking is an art, but also like making pictures and hustling collectors and galleries, it is also a business. As we regard a work of art visually, it seems apt to look at wine pictorially, as something on private display, for our private pleasure.

Who misses the connection between a place that gives us Titian and Amarone? Or one that gives us Poussin and Puligny-Montrachet? It is of a piece and it enriches us. It establishes value like Malamud infers, beyond what the maker and the viewer expect.

Reframe your wine drinking the way successful athletes anticipate taking home the big trophy and the big payday. They visualize the win. You visualize the wine.

Ken Friedenreich is writing a book on Oregon wine called “Decoding the Grape.” He contributes to various publications as a wine editor and columnist.

Ken Friedenreich is writing a book on Oregon wine called “Decoding the Grape.” He contributes to various publications as a wine editor and columnist.