Luck of the Red

Story and photos by Jānis Miglavs

The staggering statistics can tantalize like a Siren’s song. Some 25 million Chinese reach middle class status each year, many eager for the luxuries like new cars, the latest gadgets and, lucky for our industry, drinking wine.

In fact, Chinese consumers drank more than 1.6 billion bottles of wine last year, an increase of 10 percent over the previous year. Experts project this number likely to increase at the same rate or better. In just a few years, China has become one of the top 10 global markets for wine.

So why not export Oregon wine to China? Like the Sirens’ seductive tunes, exporting to China presents unique challenges, especially for the uninformed.

Foremost are the cultural and language differences, many of which I’ve blundered during my multiple trips to write and photograph wine-related articles and books. For example, some call wine báijiu (or pinyin), which is actually a hard liquor rice wine with a much longer cultural history than the more recent grape wine, pútáo jiu.

Then there is the “ganbei” style of drinking. Even executives of major Sino wineries will skip examining wine color in the glass, forgo the nosing and shout “ganbei!” Then, in one swift bottoms-up movement, swallow the entire contents of the glass. From experience, I’ve learned to have only a small amount of wine in my glass at dinners, which can last for countless “ganbeis.” Also, many Chinese prefer reds simply because red is considered a lucky color, and they’ve been indoctrinated that red wine is healthy.

Decoding your Chinese wine rep’s real name is also helpful, although those dealing with foreigners on a regular basis will often assume Western names instead of using their given ones. By the way, Chinese commonly present their family name first, then the given name, i.e. Miglavs Jānis (no comma).

Then there’s the fact that most Chinese don’t know where Oregon is, let alone that Oregon makes wine. When I say I’m from Oregon, I usually have to draw a map in the air with my hands and explain, “Here’s California, and here’s Oregon, just above California.” But when I show a copy of my picture-laden Oregon Taste of Wine book, they oohh and ahhh over the beautiful scenery. Remember, they live in highly polluted cities — hmmm, could photographs of Oregon scenics help sell Oregon wine?

Almost like the Great Wall, the Chinese market is segmented. There’s Hong Kong and Shanghai, and then there’s the mainland.

Hong Kong has emerged as a regional wine hub, primarily because foreign wines are significantly cheaper, as the former British colony doesn't charge import duties. Kilpatrick, an export broker and a founding partner of Portland-based Trade Exports, explains, “It’s more difficult for me to export to California than Hong Kong because of the regulations.” Besides, Hong Kong business folks have been involved in capitalistic commerce for years, so they generally have a better understanding of Western business practices. As a result of this easier access, Hong Kong wine buyers tend to be more sophisticated consumers.

The mainland, on the other hand, is transitioning from communism to capitalism with ever-changing rules. Currently there is a 48 percent tariff on wine going in. But that figure can change like a thermometer needle reacting to the politics of the moment, along with your shipper’s relationship to customs officials.

With a sigh, Kilpatrick lists other mainland obstacles: varying rules at each port of entry, wine labels needing to be in Chinese and rampant corruption. A customs official could pull two to 10 bottles from each pallet going to the mainland to “test” them. But who knows where those confiscated bottles end up?

Skillfully navigating those rules and tariffs are simply part of doing business in this part of the world. For example, Hong Kong’s wine merchants sell a large portion of their inventory to wealthy mainland Chinese clients, who then hire well-connected trench-coat-types to smuggle wine through “gray channels.”

“But be careful if you decide on this route,” warns Kilpatrick. “You could lose an entire shipment if the customs official decides to crack down.” China’s new president has vowed to fight corruption.

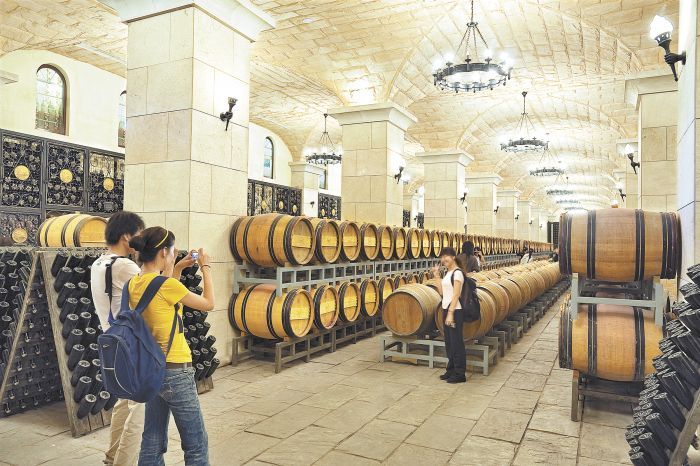

Be aware the Chinese consumer buys wine for a variety of reasons. The prestige factor is high on the list. Foreign wines are generally perceived as better than domestic, and France is king. In fact, France commands 48 percent of the imported bottles into China.

Wine is also popular as a gift, especially when trying to impress government officials or develop new business relationships. One Chinese winery specifically targets the gift trade with a single bottle of wine priced at a U.S. equivalent of $4,590 — impressive price equals great impression. But for most, the much more affordable wines are attractive to drink and give, especially for the many Chinese who thirst for wine knowledge in cities like Hong Kong, Shanghai and Beijing.

Before heeding the Siren’s call, Dewey Weddington, director of marketing and education at the Oregon Wine Board, suggests, “Step back to consider if you really want to export to China. Does it fit your overall strategy? And can you realistically do it? If your total production is 2,000 or 5,000 cases, do you have enough product?”

Finding a broker or distributor you can trust is the next step. Kilpatrick suggests, “Work with a knowledgeable person so you don’t get hosed. Develop a relationship with that person.” He also recommends asking yourself, “Will they promote your wine like a top tier U.S. distributor? What is their general knowledge of the world wine market? How will they differentiate Oregon Pinot Noir from Burgundy?”

“There are many big players looking for a cheap deal and quick turnaround,” Kilpatrick adds. “Oh yes, be sure to trademark your brand and identity, lest you find a label with your winery’s name on a bottle of some undetermined varietal bulk liquid.”

Having exported for a number of years, Ryan Harris, president of Domaine Serene, explains how distributors have their specialties. For example, they use Golden Gate Wine Co. Ltd. because they deal with ex-pat hotels and white tablecloth restaurants, perfect for the winery’s upscale market. While he inherited the distributor relationship from his predecessor, Harris has come to trust that his distributor will handle all the licensing, labeling, customs and regulations. Domaine Serene also ships to Taiwan with a different distributor, Seven Pyramid.

Ready to jump in? The Oregon Wine Board has a small list of potential brokers and distributors. Other sources of guidance include USDA’s Agriculture Trade Offices (ATO) in China. While some report limited success with them, the Shanghai ATO office helped Weddington set up the Oregon wine exhibit at this year’s Pro Wine Shanghai, featuring 10 Oregon wineries. A few have successfully connected with the US-China Chamber of Commerce. Another approach is China-based Yes My Wine, an on-line seller with sales of more than $65 million in 2012.

Weddington also suggests connecting with Oregon wineries that have had success. For example, Jennifer Kerrigan, distribution and compliance manager at Del Rio Vineyards & Winery in Southern Oregon, reports: “We have been exporting for a couple of years now and actually have had reorders. We ship Cabs, Merlot, Syrah, Pinot Noir and white blends mostly to hotels and restaurants. And we are on the brink of getting into retail.”

Finally, advises Weddington, “Be persistent but patient.” Developing relationships takes a long time, particularly in the new wine frontier.

Jānis Miglavs writes and photographs for all of the world’s major wine magazines and recently completed the definitive book on Chinese wineries, due out later this year in both Chinese and English.