Call from Switzerland

By Jim Gullo

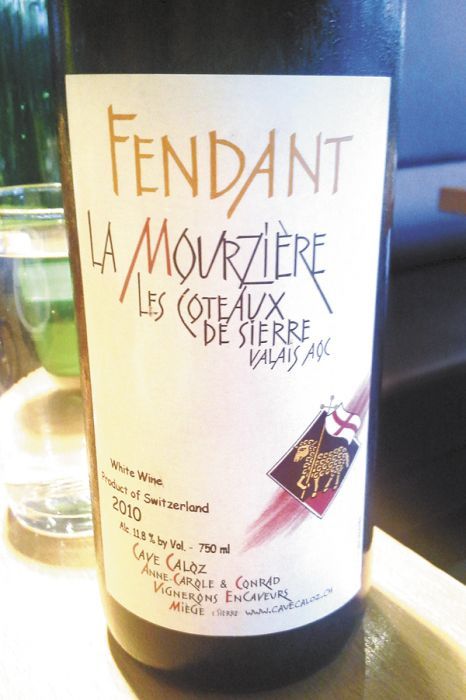

I couldn’t wait to tell Alex how his Swiss wine had once again lifted my spirits. It was last May; my mother had been in the hospital for two weeks having one delay after another over what was supposed to be emergency bypass surgery. My sister and I were soothing our nerves with a lunch at Grüner in Portland. When I opened the wine list, and there it was: a bottle of Fendant, the excellent white wine from Alex’s home canton of Valais, in the French-speaking south of Switzerland. The producer was a couple who lived nearby his native town of Sion.

“Score! We never see this stuff on wine lists,” I e-mailed Alex along with a picture of the bottle.

“That’s because we want to keep it all for ourselves,” he shot back. “It’s too good!”

And it was. Crisp, mineral, steel-edged. Just a lovely dry, white wine made from the grape that we call Chasselas but the Valaisannes call Fendant. It’s hard to find because the mom-and-pop Swiss producers make so little and export only a fraction. Indeed, a check with a wine searcher website reveals that there isn’t a bottle shop in Oregon that carries it — although Storyteller Wine Company in Southwest Portland occasionally stocks it, and owner Michael Alberty promised to bring in bottles in anticipation of this story.

What Alex wrote was true: The Swiss want it all for themselves — it goes great with raclette. Drinking it again at Grüner was like a call from Switzerland that peeled back decades for me.

Thirty-four years ago, when Alex and I met — I was doing my first, collegiate, bumming-my-way-through-Europe trip — he and his family sat me down at their kitchen table and taught me all at once about great wine, as well as the simple extravagance of a fine cheese melted right at the table and scraped onto your plate alongside boiled potatoes and pickles. I also learned European manners and hospitality, and hikes in the Alps with jaw-dropping views in every direction.

Alex was an adventurer. He took me up in a private plane and stalled it just to scare me when we seemed to be mere feet away from one of those sheer, granite mountain faces. Another time, he strapped me in to his paraglider and said, “Go ahead, try it!” I ran ten feet, caught a little air, glided another ten feet and then planted my nose in the Helvetian soil. Alex was a champion skier and fencer, and he and his parents, Albert and Marcel, were the most generous people I had ever met.

I returned to Sion two years later, chucking my magazine job in New York for another European adventure, and Alex found me work picking those Fendant grapes on tiny, terraced vineyards clinging to the side of the mountain. Ten feet from the end of a row there might be a chasm that plunged hundreds of feet down. We went to little stone cafés high in the mountains to drink more wine and eat harvest meals of roasted chestnuts, apples and cheeses. He and his father brought me to Paris for an unforgettable weekend, and paid for everything.

We passed through our 20s, married, had kids. I tried to return to Sion when I could, but time kept slipping away. Alex suddenly had four kids when I returned for a visit ten years ago, so I brought them all baseball gloves and a ball. We spent a hysterical afternoon showing them how to golf on a tiny course hacked from the side of an Alp, not far from where I had picked grapes. Alex, who could hike up mountains with a 100-pound pack and sealskins attached to his skis, and who was willing and able to fly any hang glider or ultralight plane, was utterly baffled by the mechanics of hitting a golf ball.

Last April, a few weeks before my mother fell ill, Alex wrote to me saying he would be in San Francisco on business, and why didn’t I come for a visit. It had been too long since we’d seen each other. He picked me up at the airport: Gray hair now, and some sadness lines around the eyes, but still a great sparkle and a great spirit. We hit it off again immediately, as old friends do.

We drove straight to wine country and spent a day tasting Cabs and Chards while I boasted about Oregon Pinot Noir and he boasted about good Fendant. On the way back to the city, we parked the car at the north end of the Golden Gate Bridge, and he ran while I walked up the steep paths that paid off in sweeping vistas of the city, the bridge and San Francisco Bay. “I used to get arrested here when I first came as a student,” he laughed. “I was always trying to find a place to jump off with my hang glider.”

We agreed the next meeting would be in Switzerland. He offered his whole house for my family to use — he could stay with his mother, back in the apartment. His kids had all grown up and left; his marriage had ended. We could really make a dent in the local wine scene.

Last spring was rough. The visit with Alex was one of the few bright spots. My mom survived, but needed a lot of care and rehabilitation. The week she returned to her apartment, in July, I received another call from Switzerland. It was from Alex’s ex-wife. He had been killed in Italy over the weekend when his ultralight inexplicably crashed into high-voltage power lines and incinerated before it fell to the ground.

To Alex Bezinge, I raise a glass in gratitude for having been a part of my life. And I’ll always be looking for the next bottle of Fendant to share in his memory.

Jim Gullo is a freelance writer and author living in McMinnville. His latest book, “Trading Manny: How a Father and Son Learned to Love Baseball Again” was published in 2012. He is currently working on a novel about the Marx Brothers.