Mystique in a Bottle

By Janet Eastman

The story behind the safekeeping of a 70-year-old bottle of Dom Pérignon is as effervescent as the legendary Champagne.

It involves hiding the Champagne from France’s invaders during World War II and later shipping it to the United States, where it rested, trophy like, on the home mantel of a prominent Medford businessman.

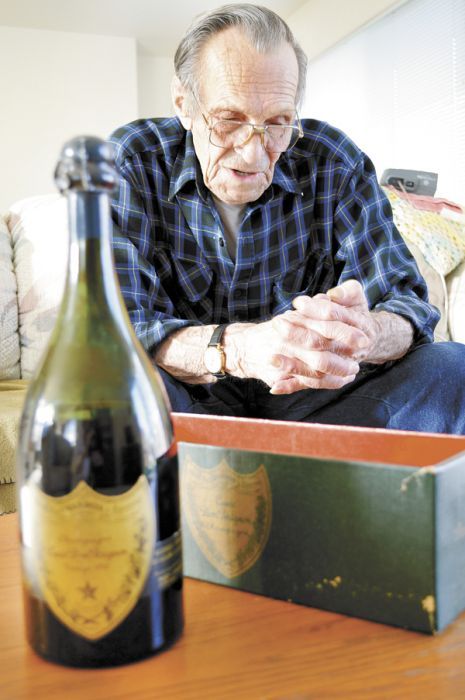

Today, the precious bottle belongs to Charles Hackett, an 82-year-old retired timber worker who knew it was special when he first spotted it.

In 1978, when he was packing the possessions of the late timber magnate Anton Lausmann at Rogue Valley Manor, he opened a forest-green box. Within, on its side, was a dark-green bottle with a shield-shaped label. Lausmann’s son, Jerry, a teetotaler who would later become the mayor of Medford, suggested Hackett pop the cork, and let the crew drink it in the dismantled living room.

“I told him I didn’t know anything about wine, but it just looked special,” recalls Hackett, sitting in his modest Medford living room decades later. “Jerry told me I could have it.”

It was a gift both delightful and worrisome.

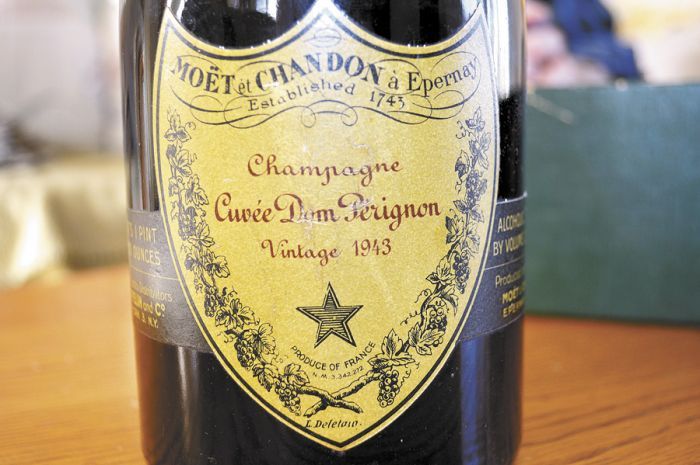

Dom Pérignon Champagne is expensive. The Pinot Noir and Chardonnay grapes used to create it come from grand cru vineyards in the fabled Champagne region of France. It was there 17th-century Benedictine monk Dom Pérignon perfected the art of capturing bubbles in a bottle.

Since the prestige brand was founded in 1921, Dom Pérignon has released only 40 vintages. The grapes are pressed and fermented, aged and babied into sparkling wine only in stellar years. The Champagne is released for sale nine years after harvest.

The most recent release is 2004; a standard 750-milliliter bottle sells for $200. Older Champagnes — if cellared properly in a cool, dark place — can command much more. A 1959 bottle of the first vintage of Dom Pérignon Rosé was auctioned off for $35,000 in 2008. A 20-year-old Dom Pérignon was served at Princess Diana’s wedding in 1981 — the 1961 cuvée was selected for her year of birth.

As the world’s most famous Champagne, millions of other bottles are being held in households, waiting for a special occasion.

Hackett’s bottle is special in itself.

It was born when the world was at war. French vintners continued to care for their vineyards when they could, often without the help of workers dispatched to the front lines, horses requisitioned into duty and winemaking chemicals and additives redirected for war use.

Stories circulate about Champagne owners building false walls in their cellars to hide their pricey inventory. Their enemies, it is said, didn’t venture into the miles-long, subterranean tunnels because they were afraid they’d get lost or be clunked on the head with a bottle. Still, uncountable bottles were taken.

The first vintage of Dom Pérignon from grapes harvested in 1921 sailed to New York on the liner Normandie in 1936 after Prohibition. Three of those bottles from billionaire James Buchanan Duke’s original case sold at Christie’s Auction House for $24,675 in 2004.

In the early 1950s, when Hackett’s 1943 bottle was released, it was imported by Schieffelin & Co. of New York, a company that evolved from being an 18th-century drug distributor to Schieffelin & Somerset Co., a top importer of premium wine and spirits.

When that bottle was making its way to the West Coast, Hackett had graduated from McLoughlin Middle School — then called Medford Senior High — and had served in the Air Force as a B-29 engine specialist during the Korean War.

Hackett worked various jobs until he was hired to sweep up sawdust at a successful sawmill owned by the Lausmann family’s Kogap Enterprises in Medford. For 34 years, he worked for the Lausmanns, retiring in 1995 after caring for the company’s and family’s real estate holdings.

No one knows when Anton Lausmann received the bottle.

“He was high up in the Republican Party, active in the logging conference, and he was in a band,” says Dee Marlow, who was Jerry Lausmann’s executive secretary and has worked for Kogap for 40 years. “Mr. Lausmann could have received it from anyone,” she says. “It’s a mystery.”

Hackett has another question: What’s it worth?

Bottles of 1971 and 1975 Dom Pérignon are listed for $2,300 each at Wally’s Wine & Spirits, a Los Angeles-based wine merchant specializing in prized vintages. Co-owner Christian Navarro, a wine consultant to former presidents and movie stars, can’t put a value on a bottle he hasn’t inspected.

But no one looking at Hackett’s bottle, which has lost about a third of the Champagne from evaporation, would suggest it be tasted.

Air has most likely tainted the aromas, flavors and bubbles. Long gone are the “wonderful base flavor and lovely, luxurious feel in the mouth” a reviewer in 1996 found in a properly stored 1943 bottle of Dom Pérignon.

Hackett slumps a little when he hears this. Then his Air Force posture returns.

“As long as it’s got the Champagne in it, it’s special,” says Hackett. “It has evaporated some. But a person with a brain would not open it. That the wine is still in there, that’s the whole show.”

Reprinted with permission from the Medford Mail Tribune.

Janet Eastman has been a staff writer for the L.A. Times and was a staff wine columnist and reporter for the Medford Mail Tribune. She recently joined The Oregonian to cover home design.