Vindicating Thomas

By Neal D. Hulkower

In the end, there was no reason to doubt Thomas Jefferson; Vitis vinifera now flourishes in the Old Dominion.

In 2010, the Commonwealth of Virginia ranked eighth in the country for total grape production and in bearing acreage. The national and international reputation of wines from the state is rising as evidenced by numerous accolades in prestigious publications and competitions. It is not unreasonable to believe Virginia will one day be able to claim the title of best American wine-producing state east of the Rockies. But the impending success did not happen overnight; it is more than 400 years in the making.

Though settlers in Jamestown produced wine from English grapes in 1609, the country’s commercial wine industry is considered to have begun in 1619 with the passage of “Acte 12” by the General Assembly of Virginia also in Jamestown. It decreed “that every householder doe yearly plante and maintaine ten vines, until they have attained to the arte and experience of dressing a Vineyard, either by their owne industry, or by the Instruction of some Vigneron. And that upon what penalty soever the Governour and Counsell of estate shall thinke fit to impose upon the neglecters of this acte.”

The intent was to make Virginia a significant source of vinifera wines for the British Empire. Unfortunately, nature conspired against the plan by visiting diseases and pestilence upon the vines. Then, as today, the climate was not too cooperative, either. Soon the vines were replaced by tobacco, which proved a quicker path to profit.

As economic cycles go, by 1759 the tobacco trade was in a depression. In response, Charles Carter chaired a committee of the Virginia assembly formed to look at diversification. He and his brother, Landon, had already been growing and vinifying native and vinifera winegrapes. Naturally, wine was high on his list of proposals; and the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufacture, and Commerce (now known as the Royal Society of Arts) in London encouraged and advised Carter in his vinous pursuits.

In 1762, the society awarded him a gold medal in acknowledgement of his “spirited attempt towards the accomplishment of their views, respecting wine in America.” His “attempt” was two wines made, one from an American winter grape and the other from a white Portugal summer varietal. One year later, Colony of Virginia Royal Governor Francis Fauquier certified Carter’s success in growing both red and white European grape varietals.

In 2012, the Virginia Senate passed a resolution to commemorate “the 250th anniversary of the first internationally recognized fine wines produced in the Commonwealth as a result of Charles Carter’s award from the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce.”

Colonel Robert Bolling Jr. was another advocate of vinifera, finding the wines made from native grapes too acidic. Between 1773 and 1774, he produced a manuscript entitled “A Sketch of Vine Culture for Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas.” It contains collected wisdom from a wide range of European sources and also specific recommendations based on his own experience planting and tending a vineyard at Chellowe. In addition, Bolling’s “Essay on the Utility of Vine Planting in Virginia,” published in a 1773 issue of The Virginia Gazette, exhorts the House of Burgesses to fund public vineyards and experimentation thereon with imported grape varietals. He was granted £50 annually for five years by the House. Unfortunately his experiments were cut short by his death in 1775.

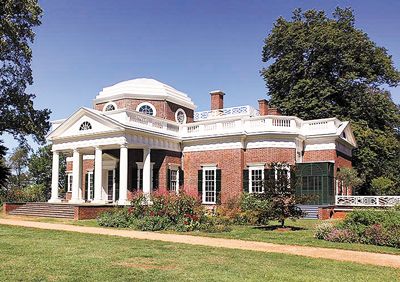

It is unknown whether Thomas Jefferson had knowledge of the success of Charles Carter or of the works of Bolling, though the two were well acquainted and shared relatives, when he planted grapevines at Monticello in 1771, thus beginning his ill-fated experiments. Two years later, Jefferson’s friend, Filippo Mazzei, arrived from Italy to assist at both Monticello and Colle, a nearby farm. The reason these efforts failed to yield a crop is a matter of debate. While phylloxera, fungal disease and inclement weather have been blamed, Gabriele Rausse, Monticello’s current assistant director of gardens and grounds, theorizes that birds and/or deer were responsible.

In response to the lack of success with vinifera, hybrid grapes, crosses between two or more Vitis species, took center stage in Virginia during the 19th century. One in particular, Norton, first cultivated in the early 1820s by Dr. Daniel Norborne Norton in Richmond, remains popular.

Norton is believed to be descended from Vitis vinifera — possibly Enfariné noir — and Vitis aestivalis; it is virtually identical to the hybrid Cynthiana. By 1830, the grape was marketed commercially by William Prince of Flushing, New York, who received it from Dr. Norton. Norton/Cynthiana was also successfully planted in Missouri, where it was named the state grape in 2003, as well as in other states east of the Rockies.

In 1873, the Monticello Wine Company was founded in Charlottesville; in the same year its Norton-based “Extra Virginia Claret” earned national and international acclaim. Today it is used to make a range of styles from rosé to dry red table wine to port. Leading Virginia producers include Horton Vineyards and Chrysalis Vineyards.

Monticello Wine Company became the largest winery in the South, but its success was cut short in November 1916, when Prohibition took over the Old Dominion more than three years before the 18th Amendment took effect. In 1949, 16 years after the 21st Amendment was passed, John Baptista Sciutto started his eponymous winery on the grounds of the Manassas Battlefield Park. Until he was forced to close in 1955, he produced wine from Norton and vinifera grapes.

In his book, “Beyond Jefferson’s Vines: The Evolution of Quality Wine in Virginia,” Richard G. Leahy writes “…the renaissance of the Virginia wine industry began in the late 1960s around the town of Middleburg, in the northern Piedmont east of the Blue Ridge Mountains…The post-Prohibition pioneers grew hardy French hybrid varieties…to avoid the vineyard woes experienced by Jefferson and the Jamestown settlers, setting the pattern for small Virginia wineries for the next twenty years.”

In 1973, the Vinifera Wine Growers Association (now the Atlantic Seaboard Wine Association) was founded and, in the same year, planted Chardonnay, making it the first commercial vinifera varietal grown in post-Prohibition Virginia. Favorable legislation followed in the 1980s, creating a most congenial environment for growing and producing wine from Virginia grapes. In 1984, a fund was created using an excise tax on Virginia wine to fund research and staff positions at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech), which has since become a major contributor to the growth and success of the state’s wine industry.

Also around this time, the emphasis shifted from the French hybrids to vinifera. Sometime in the 1990s, I remember tasting my first Virginia wine, a completely forgettable Riesling, at an American bistro in Reston, which at the time carried only domestic wines of which this was the sole representative from the state. Along with Cabernet Sauvignon, Riesling plantings diminished because of its inability to withstand humidity. The cultivation of vinifera grapes finally overtook French hybrids in the mid-1990s; successful varieties include Viognier, Cabernet Franc and Petite Verdot.

The industry is typically aided by academic institutions, like Virginia Tech, training future generations of grapegrowers and winemakers and conducting innovative research into farming and winemaking methods. Sensible legislation also enables responsible growth. Leahy notes “Important steps forward were realized in 1980 and 1985 with the passage and reauthorization of the Virginia Farm Winery Act, establishing favorable tax and regulatory status for wineries with their own vineyards and small commercial production using Virginia grapes.”

Consultants and itinerant winemakers are employed to bring state-of-the-art practices home to the point of production. Virginian Lucie Morton shares her considerable expertise with several commonwealth wineries. Claude Thibaut moved to Virginia from Champagne to produce sparkling wines. Boxwood Estate Winery employs Stephane Derenoncourt to bring Bordelaise expertise to Middleburg. And savvy marketers like Christine Iezzi of Country Vintner seek to brand wines from newer regions and define their place on the increasingly crowded wine market.

With the help of the Virginia Wineries Association, founded in 1983, Virginia wine is creating its own identity and others have taken notice. The prestigious UK wine publication, Decanter, and other publications and noted critics regularly give high ratings to many of Virginia’s wines. Currently with 210 wineries, the wine scene in Old Dominion is certainly well advanced along the evolutionary path.

When benchmarking the state’s progress, some Virginia winemakers and experts cite Oregon. Leahy, Rutger de Vink, founder of RdV Vineyards, a new high-end winery dedicated to Bordeaux blends, believes Virginia is in a position similar to where Oregon was 25 years ago.”

According to de Vink, “The challenge in Virginia is that it’s too easy for us to sell our wine here. Oregon was forced to improve quality as well as specialize and associate itself with Pinot Noir. Now, they’re planting on the correct soils. My hope for Virginia is that it follows the same trend, going for a focus on site selection, not on what’s best for tourism but for where the best grapes are grown.”

From late-2004 to mid-2011, I resided in Alexandria, Va. Being a committed “loca-pour,” I began to visit nearby wineries in hopes of finding a more pleasant experience than that unfortunate Riesling. Bordeaux blends, Chardonnay and a Seyval Blanc from Linden Vineyards were the first to please my palate. A bargain Cab Franc named Marquis de Lafayette from Breaux Vineyards so delighted me that it displaced an Oregon Pinot Noir as my Thanksgiving wine one year. Horton Vineyards 2001 Tannat — tasted at five years old — could have been mistaken for one from Madiran. The first Nebiollo harvested at Three Fox Vineyards was amazing. The Williamsburg Winery Gabriel Archer Reserve from the late 1990s could easily pass for a fine classified-growth Claret. From these and other great experiences drinking Virginian wines, I can attest the state’s industry has gone from mostly mediocre to progressively more meritorious.

Virginia wines occupy the middle ground between Old and New World but gravitate more toward Europe than the West Coast for inspiration. The overall impression is stately but not stuffy. There are no fruit bombs; instead, fruit plays nicely on the palate with other flavors. Critics have compared Virginia Viognier to Condrieu and its Cabernet Franc to those from the Loire. It is no surprise that the British, historically major consumers of French wine, are going gaga over those from the commonwealth.

Grapegrowers and winemakers in Virginia face both different and similar challenges as those in Oregon. Because of the particularly humid climate and rainy summers, sustainable practices seem to play a secondary role to aggressively fighting various diseases and pests, though one winery, Annefield Vineyards, is listed as being Biodynamic in Leahy’s book. Like Oregon, Virginia is increasingly attentive to green building practices. Gold and platinum level LEED-certified tasting rooms can be found. Both states are struggling to define the proper balance between alternative uses of wineries for events and other forms of tourism and responsible stewardship of precious farmland.

Into their fifth century, Virginia wines have finally earned a genuine claim to gravitas. Post-Prohibition reconstruction of the industry followed the best practices resulting in a uniquely American East Coast expression that still pays homage to Europe.

“I always say that there has to be tradition around something to make its branding work,” foremost American wine educator Kevin Zraly told Leahy. “Virginia has it more than California, thanks to Thomas Jefferson.”

Neal Hulkower is a professional mathematician and avid wine collector/winery volunteer living in McMinnville.

Oregon-Virginia Comparative Tasting

On Nov. 4, a bicoastal blind tasting of Oregon and Virginia Viogniers and Cabernet Francs was held. Panels comprised of distinguished professionals from the food and beverage industry convened at the offices of the News-Register in McMinnville and the Wine Loft in Short Pump, Va. Three viogniers from each state were sampled in the first flight followed by a second flight of three Cabernet Francs from each state.

The dozen wines selected to compete survived a careful vetting. The Oregon contenders were chosen after sampling a wide assortment and include three medal winners, one that was Best of Class in the 2012 San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition. The Virginia challengers, five of which were gold or silver 2012 Governor’s Cup Medal Winners, were chosen by the organizers on the East Coast. Each of the 11 judges, six in Oregon and five in Virginia, ranked the wines in each flight, with ties permitted. The Borda Count was used to arrive at the consensus ranking. (Search “Borda is Better” on www.oregonwinepress.com for an explanation.) Each judge’s ranking was converted to a Borda scores as follows: The top ranked wine received 5; the next, 4; and so on down to the sixth rank wine, which received 0. The Borda score assigned to each wine by each judge were totaled and ordered from the largest to the smallest sum to arrive at the consensus ranking.

While two Virginia wines led, the Borda scores of the top five viogniers ranged from 33 down to 28.5, indicating that the aggregated judges’ preferences were very close. The story was much different with the Cabernet Francs. The top two had Borda scores of 47.5 and 43, while the remaining four ranged from 24 down to 15.

Viognier Ranking: 1. King Family 2011 Viognier (VA); 2. Narmada 2010 Viognier (VA); 3. Spangler 2011 Viognier (OR); 4. Troon 2011 Viognier (OR); 5. Michael Shaps 2009 Viognier (VA); 6. Del Rio 2010 Viognier (OR). Cabernet Franc Ranking: 1. Sunset Hills 2009 Cabernet Franc (VA); 2. Spangler 2009 Cabernet Franc (OR); 3. Troon 2010 Cabernet Franc Reserve (OR); 4. Jefferson Family 2010 Cabernet Franc (VA); 5. Cliff Creek 2007 Cabernet Franc (OR); 6. Barboursville 2009 Cabernet Franc Reserve (VA)

Virginia Produces Pinot?

So the 11 judges in Oregon and Virginia ranked Old Dominion Viogniers first and second place and a Virginia Cab Franc first over Southern Oregon bottlings. Maybe we should not be surprised, since these two varietals are widely touted as Virginia’s pride and joy. But what about Pinot Noir? Does Oregon need to worry about increased competition from Ol’ Virginny in regard to our state’s celebrated wine grape?

Dennis Horton of Horton Vineyards told Leahy: “I don’t think Jesus Christ could grow Pinot Noir in Virginia. You can do it, but it doesn’t taste like Pinot should.” DrinkWhatYouLike.com blogger Frank Morgan conceded, “In past years, I’ve found many Virginia Pinots to be insipid wannabes, showing no resemblance to the varietal beauty that can be Pinot Noir.”

But prompted by an enthusiastic review posted in July 2011 by David McIntyre, Washington Post wine critic and blogger, I had to taste the 2010 Ankida Ridge Pinot Noir, the tiny winery’s first release made from grapes harvested from vines planted in 2008 on 1.5 acres at 1,800 feet on the slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

To make things interesting, I tasted it side by side with an Oregon Pinot Noir, the 2010 DePonte Cellars Lonesome Rock Ranch, the first made from grapes planted in 2007 in the foothills of the Coast Range in Yamhill County in the Willamette Valley.

Immediately upon opening, the medium dark-colored Ankida Ridge put forth an intense, almost jammy floral, fruity nose but sat lightly on the palate with medium tannins. The jamminess became more pronounced with air. The medium-light-hued Lonesome Rock Ranch offered a more masculine nose of forest floor, fruit and flowers with hints of hay and herbs, and much tighter structure. Flavors leaned more toward the floral and fruity and, with air, some vanilla and spice. The flavors were more focused; the balance, better; the structure, tighter; and the finish, longer than the Ankida Ridge. This was unmistakably an Oregon Pinot Noir. After about three hours of air, a pleasant hint of minerality emerged on the nose of the Ankida Ridge, and the jamminess gave way to pretty spice over fruit and flowers. The three who tasted with me definitely enjoyed it.

Noted wine writers Jancis Robinson and Eric Asimov told McIntyre, “It tasted like Pinot!” and I certainly agree. On the other hand, I also agree with Morgan, who wrote in August 2011, “I’m not sure I will ever be completely sold on Virginia Pinot Noir, but one of Virginia’s newest wineries, Ankida Ridge Vineyards, is opening my mind to the potential of Pinot here in the Commonwealth.”