Art of Chardonnay

By Jennifer Cossey

Cherished by many who consider it one of the world’s greatest treasures, Chardonnay has gotten a bad rap from a slew of inexpensive, over-oaked versions that once flooded the market. While there was, and still is, a palate for that style — imagine buttered popcorn — the majority of people turned their attention toward lighter, more approachable white wines. Ever heard about the wine club called ABC, or Anything But Chardonnay?

The noble white has been misunderstood as it comes in different shapes, sizes and personalities. Some are fruity and tropical. Others are floral. Yet some have mineral notes. Chardonnay can be full-bodied, rich and voluptuous, or it can be ethereal.

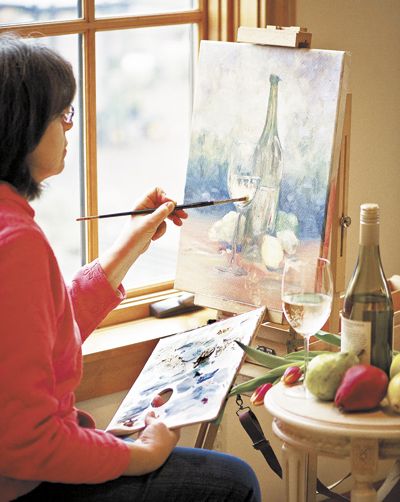

The wine’s taste experience is vast and variable, making it one of the few wines that producers compare to an artist’s canvas. Chardonnay is a variety waiting for the influence and brushstroke of a winemaker.

In Oregon, we have a love affair with Burgundian wines, especially Pinot Noir. But it is Burgundy’s white that has a growing number of local ardent supporters. Although acreage has decreased — from 1,500 in 1995 to 950 in 2010 — love for the wine grows as more Oregon producers are attempting to craft their own Chardonnays.

The quest toward Oregon perfection is not new. Pioneers like Richard Sommer in the Umpqua, and David Lett and Dick Ponzi in the Willamette Valley planted some of the first Chardonnay vines in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Ponzi's first Chardonnay plantings in 1970 utilized clonal selection 108, also called the Davis Clones — named after the California university and research facility.

Others followed suit, planting 108 as well as Wente and Draper. The vines, brought up from a warmer California, seemed to grow well enough at first, but problems began occurring. They tended to ripen late, especially in colder years. Yields were low, and the dominant flavor profile was unfavorable, inconsistent and uninspiring.

A handful of pioneers believed strongly that despite the initial disappointments of the initial clones, the climate and soil, particularly in the Willamette Valley, could lend itself to world-class Chardonnay production. It was around this time that one of those pioneers, David Adelsheim, of Adelsheim Vineyards, embarked on an education and research trip to Burgundy.

He didn’t go to France solely with the purpose of finding innovations for Chardonnay, but as luck would have it, that’s just what happened.

“Before I left in the fall of 1973, there had been some interest in different clones,” Adelsheim said. “Up until that point, people didn’t really know there were subset varieties.” He ultimately returned to the States with new clones of Chardonnay called Dijon.

In 1985, following an intense quarantine, the Dijon clones became available to winemakers and vineyard owners. But, at the same time, more Pinot Noir vines were being planted and Chardonnay was losing valuable acreage in Oregon.

The costs associated with pulling out vines and replacing them with an unproven clone were expensive for a young industry. It was not a risk most people were willing to take. Those who tried the new clones were pleased with the marked improvements in regard to yield, consistency and flavor profile.

Though work still needs to be done in clonal research, producers using Dijon are, in large part, pleased with the outcome thus far. Of the Chardonnay planted in Oregon, about one-third still remains dedicated to the 108 clone. Those planted to Draper and Wente also continue to thrive as they increase in age and as the winemakers and winegrowers improve their techniques. Particularly in Southern Oregon, Draper and Wente are the clones of choice because the warm temperatures negate the grapes’ propensity to ripen late, thereby improving quality.

For winemakers, choosing the right vines is only the first step. Next, decisions must be made as to how they want their Chardonnay to taste. Several choices in production (see sidebar) offer the winemaker ample opportunities to “paint” their singular version, adding a unique signature.

“The best part about making Chardonnay might be the varietal’s ability to absorb the winemaking choices and still show what’s at its core: the fruit,” said Eric Hamacher, owner and winemaker of Hamacher Wines in Carlton. “The perception of Oregon Chardonnay is at, or just passed, a bit of a tipping point. It was not so long ago that just getting somebody to try it was a victory of sorts. Although we’ve not made a lot of Chardonnay in the last decade, what has been made has made a very positive impact.”

In the late ’90s, the first wines made from Dijon clones were released, and the results were encouraging, but the work had just begun.

“It was a very slow learning curve in the beginning,” said Adelsheim. “By 1999, there were a range of really good wines being made from these new clones; so the subsequent decade was dedicated to figuring out what style these grapes needed to be made into. There was a lot of collaboration, particularly in ORCA.”

In 2000, the Oregon Chardonnay Alliance (ORCA) was founded so those dedicated to this noble white could work together toward a common goal: world-class Oregon Chardonnay. The group’s initial seven members included Adelsheim, as well as Rollin Soles from Argyle, Harry Peterson-Nedry of Chehalem, Véronique Drouhin of Domaine Drouhin, M. Eleni Papadakis of Domaine Serene, Eric Hamacher of Hamacher Wines and Luisa Ponzi of Ponzi Vineyards.

“Several wineries that had begun making Dijon clone Chardonnay got together to see how we could improve the breed, viticulturally, winemaking-wise and in marketing or awareness,” said co-founder Harry Peterson-Nedry. “We met in everyone’s cellars, did vineyard reviews, compared vintages and process differences and put together market work to get the message out that Oregon Chardonnay had been radically improved.”

A high regard for working together is a characteristic that has always set Oregon apart from other winemaking regions.

“The thing that has brought Oregon Pinot Noir as far as it has come is a combination of collaborative thinking about how we make things and what the result of our winemaking is,” said Adelsheim.

He and the others hope Chardonnay will achieve the same success as Pinot Noir.

Of the 950 acres planted to Chardonnay, only a little more than half are in the Willamette Valley. The white can also be found in the Gorge and throughout Southern Oregon.

Michael Wisnovsky, owner of Valley View Winery in the Applegate Valley, is confident the future success of Oregon Chardonnay.

“There is no other variety that we produce that sells as well as Chardonnay all year and at every holiday, event or dinner,” said Wisnovsky.

Bryan Wilson, winemaker for Southern Oregon’s Foris Vineyards, agrees: “Our warmer and drier climate generally ripens the fruit well with less botrytis pressure. There has been good Chardonnay grown in Southern Oregon for many, many years, but we may have been behind on winemaking; we are catching up quickly.”

The love of Chardonnay and the desire to see it become something more is so strong that sommeliers, winemakers and vineyard owners have come together to promote the grape. In February, an event hosted at Red Ridge Farms brought together winemakers from Adelsheim, Durant, Evening Land, Lange and Matello. Along with the respected winemakers, advanced sommelier Erica Landon led an educated discussion and tasting focused on the history, current status and future of Oregon Chardonnay.

Across the board, winemakers feel the future of Oregon Chardonnay is bright. Véronique Drouhin of Domaine Drouhin Oregon is a big believer. “It will still take a little time for Oregon Chardonnay to get the recognition it deserves, but there is no question that Oregon Chardonnay is now world class.”

A renaissance of Oregon Chardonnay is upon us. As winemakers freshen up their palettes, wipe down their easels and set to work creating what will become celebrated as one of the state’s great masterpieces: Chardonnay.

Jennifer Cossey is a certified sommelier through the Court of Master Sommeliers and a certified specialist of wine through the Society of Wine Educators. In addition to OWP, she writes for a number of other wine/culinary publications.

WINEMAKER'S PALETTE

Winemakers have many options when deciding how to influence their wine:

1. What clone to use…

2. What vineyard to source…

3. Whether to allow skin contact, and if so, how much…

4. When and how to press the fruit…

5. How to clarify and adjust…

6. Whether to add yeasts or to allow for spontaneous fermentation…

7. What kind of fermenters to use: steel or barrel…

8. How much, if any, malo-lactic fermentation…

9. Whether to leave wine on the lees, and if so, how often to stir them…

10. What type of barrels (old vs. new, high toast vs. low, American vs. French vs. Hungarian), if any, to let the wine mature and/or ferment in and for how long…

Click here for tasting notes on 33 Oregon Chardonnays.