It’s Tricky

By Mark Stock

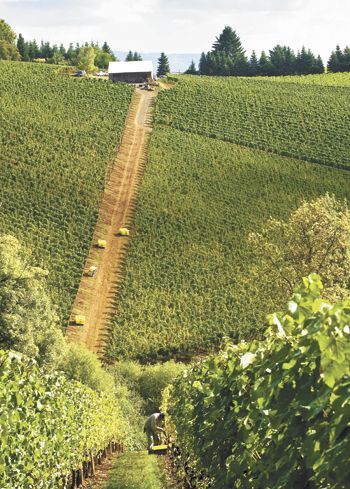

The rewards of stress are front and center in viticulture. There’s the Mars-like terrain of Argentina, home to some of the highest elevation vineyards on the planet. There are the stacked vineyard slopes of the Mosel in Germany, where steep-slope Rieslings grow in heart-shaped patterns to simplify picking on grades so grand, machinery simply can’t reach them. There are also the sheer faces of the northern Rhone in France, where death-defying Marsanne clings to 60-degree slopes on the west bank of the river.

Risky as it may be, for both vine and vineyard crews, the ends have always justified the means. In Oregon, AVAs like the Dundee Hills, Applegate Valley and Chehalem Mountains — which translates more or less to “gentle land” — conjure up pleasant images of rolling foothills but nothing extreme. Yet, within the land’s many wrinkles — etched out over time by the careful hands of geology — there exist topographic scenarios requiring special attention at harvest time. In those cases, pickers opt for soccer studs over rubber boots, and vines produce clusters so small and concentrated one might mistake them for off-colored pine cones. The ends, to reiterate, do justify the means.

In Gaston, Trudy Kramer leads Kramer Vineyards. One of her sites is the appropriately named Cardiac Hill — back in ’94, a family friend picked just four buckets of Gewürztraminer before becoming physically exhausted. The block is steep and, having once held only a couple of struggling apple trees, Kramer knew this would be a tricky vineyard. After planting vines, resident deer, among other factors, foiled Kramer’s initial endeavor. Soon thereafter, in 1995, Pinot Noir was planted, and yet the yields continued to be limited. Again, pickers winced as they navigated the challenging contours of the vineyard. By 2005, Kramer harvesting just enough fruit for 100 cases of wine.

Such challenging conditions make for memorable wine. Sure, those involved in the crush can taste the sweat and twisted ankles involved in harvesting the fruit. Bias aside, there is character in wine produced from stressed vines. Roots are forced to dig deeper, vigor ensues, and the plant is made to focus wholly on the few clusters it has to offer. Picture a gasping vineyard like you would a composition of Philip Glass: minimalistic on the surface, but packed with so much complexity and meaning it makes your head sore. To borrow from the closet of clichés, it’s about quality, not quantity.

At Élevée Vineyard in the Dundee Hills, density offers the greatest obstacle. Tom Fitzpatrick’s 14-year-old vines thrive en masse, at more than 3,000 per acre. Narrow equipment is needed to navigate the hedge maze that is Élevée. Smaller tractors offer less horsepower and low-set vines demand a bigger lunge with picking fruit. All of this adds up to a more time-consuming harvest.

The philosophy behind Fitzpatrick’s seemingly crowded vineyard is this: Less direct sunlight yields a more even ripening period. A bit less sun cast directly on the fruit has a “tempering” effect on light capture, according to Fitzpatrick. This can be more difficult during cooler vintages, but he and his team respond with increased leaf pulling for additional exposure. The compact environment can have a positive insulating effect as well, keeping chilly winds at bay and welcome warmth within.

“However, it can also lead to increased disease pressure, particularly late-season botrytis,” Fitzpatrick said. He counters this with carefully spaced clusters and finely timed spraying. As for birds, fine-feathered fiends for most vineyard folk, Fitzpatrick again touts the solidity of his vineyard. “The birds seem much less comfortable entering into our dense canopy,” he added, making the birds’ own harvest of picking and pecking, a daunting one as well.

A few topographic lines over is Archery Summit’s Arcus Vineyard, an intimidating site that spills into a large bowl behind Winderlea and Crumbled Rock wineries. Here, yields barely crest two tons per acres, and the fruit ripens 20 inches from the ground. More to the point, the rows are lined with bumpy terrain and slick rocks, the remnants of long-ago floods and weathering. The slopes are too stacked for traditional fruit-picking methods, so pickers are forced to schlep fruit via FYBs — “funny yellow bins” or “f-ing yellow bins,” depending on who you ask and how far into harvest you are — in and out of blocks to areas larger equipment can reach.

Said bins weigh about 20 pounds each when full. The crew carries them out of the vineyard rows where they’re positioned on pallets and transported to flatter ground where larger trucks can safely travel. It’s a multi-step operation that consumes buckets of time but yields tremendous fruit.

Leigh Bartholomew, director of vineyard operations at Archery Summit, knows the hillside well. She sports a new pair of soccer cleats every harvest season. Stretching a neck to gaze at Arcus and Archery Summit’s estate vineyards, you’d think professional climbing equipment would be necessary. The vines appear almost stacked atop one another, the brainchild, seemingly, of an ancient Mayan gardener.

Bartholomew reflects on certain challenging vintages. She thinks from her breadth of experience. Sure, the vineyards alone are daunting, but she shifts her tone when discussing the problems Mother Nature presents. “When it’s wet, the vineyard is filthy, the rows are slick, and the fruit can collect a lot of debris,” Bartholomew said. She recalls 2010, the year her vineyard workers laid tarps over bins to keep the rain from spoiling the fruit. Somebody peeled the tarp back every so often to let in the next load of fruit.

“One year, the crew had been picking most of the day, and Arcus was the last stop,” Bartholomew continued. “One of our older pickers looked at the site and made his mind up right away, saying ‘I’m not picking that block.’” With a little encouragement and a few deep breaths, he ended up winding through the steep rows of Arcus. But the griping wasn’t without merit. Most conclude that there’s not a big enough pat on the back in the world for deserving fruit pickers. Their constant lunging and robot-like endurance should be the toast of every bottling.

Cliff Anderson of his eponymous vineyard and label grows grapes on ground once inhabited by cherries, plums, strawberries and filberts. The previous owners even tried raising cattle on “Billy Goat Hill,” but the terrain embraced blackberries and not much else. When the idea of a vineyard came to the fore, the first contractor advised Cliff and his wife, Allison, to plant Christmas trees instead.

Naysayers be damned, Oregon wine country proves time and time again. They planted in the flatter areas and then, after a trip to Europe, were inspired to cut terraces into the steepest terrain and plant there as well. Unfortunately, the pocket gopher loves inclines such as this, an animal that, according to Cliff, “can turn terraces into Swiss cheese.”

The inherent stress makes for hard-fought flavor and grape personality, but Cliff offers an additional point. He stresses “balance,” achieved through well-draining soils that inspire roots to dig deeper and vines to flourish. Cliff waxes Darwinian, describing the ideal site, which requires the vines to labor to produce attractive fruit that will, in turn, be consumed by animals and carry on through seed dispersal. It all boils down to propagation of species, after all.

To the south 150 miles, the scene is more like a ski slope than a vineyard. Abacela’s Cobblestone Hill boasts dramatic topography and dry, rock-riddled soils. The South Face block of this vineyard offers an impressive slope, rendering rubber-tired vehicles virtually useless. Farming here is carried out by caterpillar-esque vehicles armed with steel tread.

Earl Jones, who started Abacela with wife Hilda back in the mid-1990s, brings up an interesting factoid. “Keep in mind that a typical dump truck dumps its load at around a 36 percent slope,” Jones said. “South Face has a 42 percent slope.” The block is so steep that gravity steals any fruit buckets set on the surface. Jones remarks that crew members utilize the trellis system for support as they navigate the terrain. I can’t help but picture the long line of roped-together climbers so commonly associated with scaling Everest or K2.

Of course, there is reasoning behind all of this downhill vineyard slaloming. In early spring and late autumn, when resident South Face Syrah is hungriest for warmth, the steepness of the site allows the sun to reach the surface more directly. According to the methodical Jones, the sun strikes “23 degrees closer to perpendicular than flat ground.” The valley floor equivalent would be to farm closer to the equator, thus attracting additional required ripening heat. The combination of latitude and climate, Jones continued, makes for the best Syrah under the Abacela label.

Hearing vineyard managers and winery principals discuss these challenges with such even demeanors suggests a lot. Call them necessary evils, pesky obstacles or the makings of an exhilarating adventure. Factors like steepness, density and a soil surface that feels more like cobblestone draw a lot of sweat but produce real results in the cellar. Harvest in wine country translates loosely to poor footing, long days and rubber legs. But within these precarious rows, away from most machinery, the hands-on and meticulous themes of Oregon winemaking are in full display. Even if a little sore and panting.

Mark Stock, a Gonzaga grad, is a Portland-based freelance writer and photographer with a knack for all things Oregon. He currently works at Vista Hills Winery.