Historically Honeywood

Oregon’s 80-year-old fruit winery celebrates rich past

By Ken Friedenreich

Wine enjoyment and wine lore resemble baseball — each a version of the pastoral. Both pastimes are defined by place — one can say Rogue River or Côte-d’Or, and the initiated know exactly what’s meant — like mentioning “the Green Monster” or “the House that Ruth built.”

To place, we add memory and statistics, for both wine and baseball revolve about these poles. Both glorify in good years; both endure subpar seasons — remember the Willamette Valley vintage of 1984? Thus the history of each is loaded with subjective recall inspiring passionate assertions.

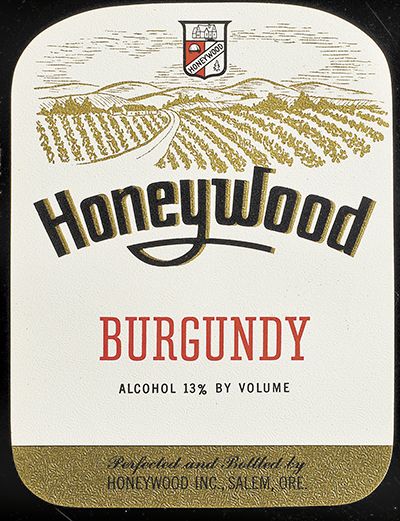

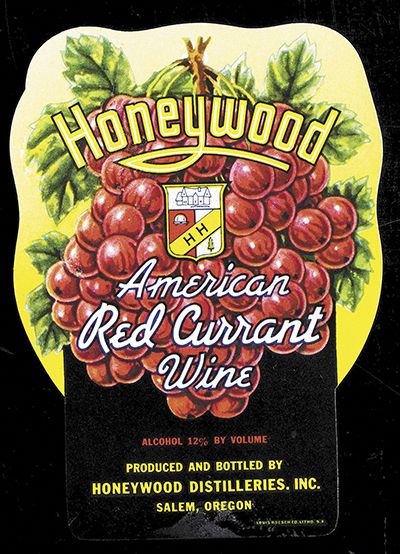

If you care about stats, swirl on this: In 1933, John Wood and Ron Honeyman received bonded winery license No. 26 shortly after the repeal of the 18th Amendment, which established Prohibition in 1920. Honeywood, then called Columbia Distillery, continues to hold the low number to this day and is the oldest continuously operated fruit winery in the state. What happened to numbers 1 to 25? It’s like asking who played first base for the Yankees before Lou Gehrig — it’s Wally Pipp; you can look it up.

In fact, when Richard Sommer planted those first fabled Pinot Noir cuttings in the Umpqua Valley, Honeywood was almost 30 years in business. Four decades later — and in the hands of the people who acquired the Honeywood brand the same year Gerald R. Ford became president — this singular heir to the post-Prohibition fruit wine boom soldiers on.

The present facility stands close to the original wood-frame warehouse, and it is more plant than pastoral. Within, Marlene and Leslie Gallick preside over a kitschy assortment of wine accessories and paraphernalia, not to mention more than 50 SKUs of ciders, fruit and viniferous wine. It’s fun without being cheeky. “Beaver Believer?” Well, almost.

Eighty years young, the business has survived its share of challenges and almost closed in 1963, before its office manager, Mary Reinke, bought the business at the behest, as she recalls, of local investors who most likely enjoyed wine.

At 94, she is likely the Oregon wine industry’s most venerable and vivacious citizen. She was 15 when Prohibition ended, a bright young adult who graduated from high school and began a distinctly liberated professional life that ended 40 years to the day from the 1934 launch of what would be called Honeywood.

A daughter of Italian immigrants and born in The Dalles, Reinke and her family moved to Salem. She recalls that her bedroom stood directly above the cellar where her father made his own wine, as was the custom among old country arrivals to the New World. “I heard a tap-tapping on my floor,” she remembers, “as corks flew out of fermenting bottles.”

After graduation, she took business and secretarial courses, landed a job at a credit bureau and, along the way, mobilized a party and wedding planning business.

Reinke began working at Honeywood in 1943. One can imagine this energetic woman 70 years ago, happily scampering over 10,000 gallons of wine held in huge redwood casks long since replaced by stainless steel.

She oversaw a myriad of business functions. “I was a good study and jumped whenever John Wood growled at me,” Reinke recalled.

Honeywood installed its first bottling machinery in the mid-1950s, and cases rolled out to the loading platform, about 1,200 bottles per day. Evolving fashion and tastes gradually caught up to the winery, and nearly 30 years after its beginning — out of the shadows of Prohibition, the Great Depression, World War II and beyond — Honeywood Winery faced bankruptcy: a crisis turned opportunity for Reinke.

Reinke recalls being asked by the shareholders to rescue the business. She was aware of the financials but was committed to making it work. And so, in the time of tail fins and Sandy Koufax, she purchased Honeywood Winery.

No stranger to publicity, this demure lady with bouffant hair and a huge Bundt cake in hand, often appeared in local newspapers or other media. And she had just begun.

The regulatory reforms Reinke instigated were sound business practice. She foresaw, to a certain degree, that wine tourism could move product and that consumers liked the convenience of sampling wine where it was made — today’s tasting room — and thus, where they could acquire it.

Reinke was good press, too. She retained her profile as a woman who entertained. She had her own advice column, an unabashed marketing tool. And she traveled the national market promoting what were now her wines. Her presence in the largely male-dominated industry was one part novelty and two parts savvy. She integrated her party planning, her recipes and her wines into what we now call “life style,” when American quaffing preferences were mostly beer and spirits.

In 1974, a Minneapolis group acquired Honeywood, and the Gallick family still operates it. The original building was sold to Willamette University and the University of Tokyo in 1991; the present facility and lively tasting room stand diagonally across the rail line from the original building.

Today, the winery produces 30,000 cases a year, and the Gallicks assert the wine is considerably drier than in the past, though it’s impossible to miss the fruit. Honeywood also produces viniferous wines from established growers and its own estate, 21 acres in Eola-Amity Hills.

And yet, as Leslie Gallick points out, Honeywood is an anomaly. “We have to lobby hard to get the wine writers’ attentions.” Think elderberry wine without thinking Arsenic and Old Lace. After a pause, she adds, “We’re typecast: wines for spinsters. But we are far more than that; we have a large and varied portfolio, and a good following.” Their 2012 Pinot Noir argues against the pigeonhole.

Even 40 years after relinquishing Honeywood, Reinke has a cordial relation with the Gallick family who helped facilitate meeting the former owner.

At the end of that conversation, Reinke looked pensive. Then she said. “My only complaint at my age is the bursitis in my hands. I can’t pull the lever on the slot machines.”

Will fruit wines enjoy resurgence? Perhaps the growing local distillers’ offerings will pique the palate for wines originating from a cornucopia of plump berries and golden hanging fruit. It might even reduce the angst in some tasting rooms where the fruit wine heritage of the Oregon wine industry has been overlooked if not forgotten.

Ken Friedenreich is the wine editor for California Homes Magazine. He likes Oregon wines well enough to now move to Portland while he works on his book “Decoding the Grape: Stories from the Oregon Wine Country.