Olden Days of the Dairy

By Christine Hyatt

Growing up a mere two hours north of Philadelphia practically guaranteed a childhood steeped in awareness of and appreciation for colonial American history. On the history of the evolution of the West Coast, however, my background was much more limited.

My latest project, producing a 100th anniversary documentary for Oregon Dairy Industries (ODI), a trade and academic group formed to promote and elevate interest in the dairy products of the Pacific Northwest, has proved a fascinating lens through which to view the development of the West Coast.

This small slice of history touches on westward expansion, agriculture and the growth of a nation. It explores the unique and effective public-private partnership that developed among the Dairy Science program at Oregon State University, Oregon dairies and the processors who bring products to market.

Dark chapters include extensive consolidation and a changing rural and food economy with interesting sidetracks into the evolution of probiotics and the influence of the counterculture.

Perhaps most interesting is that, while other states rely increasingly on large-scale centralized models of bringing dairy to market, Oregon has maintained a higher-than-average number of small, independent dairies and processors who produce a wide range of products from fluid milk, butter, cheese and ice cream using some of the highest quality milk in the nation.

The future is hopeful with a few stalwart family operations, which have managed to survive and thrive for generations, and an emerging renaissance in cheese and dairy production for local consumption and export.

I found the project fascinating and thought it might make for an interesting column or two. Hope you feel the same!

Early History of Oregon Dairy

The history of dairy in Oregon dates back to the days when the area was still a disputed territory with French, British, Russian, Spanish and American claims on the land.

In 1836, American Navy officer and diplomat Lieutenant William Slacum (1799-1839) was selected by President Andrew Jackson to explore the area and evaluate its potential for statehood. He arrived via the ship Loriot by way of the Columbia River.

In his report, Slacum stated: “I consider the ‘Willhamet’ to be the finest grazing country in the world.” He noted there were “no droughts” as in California and Buenos Aires. Instead, “the ground abounds with richer grasses, both in winter and summer.” He concluded that “Dairying could become one of the greatest industries in the Oregon Territory.”

Slacum helped pioneers organize a joint venture to procure cattle not owned by the Hudson Bay Company, a powerful British interest that leased cows to settlers.

Led by fur trapper and trader Ewing Young, settlers formed the first joint venture in the territory, the Willamette Cattle Company. Slacum even financed part of the venture with $500 to cover expenses. Another $1,100 was raised from the settlers themselves who became stakeholders in the company.

In January 1837, Young and several others joined Slacum on his ship and sailed for San Francisco, where they purchased 700 head of cattle and drove them northward over the Siskiyou Mountains and into the Willamette Valley.

About 100 head were lost to the “adversities of the trail, the natives of the Siskiyou Mountains and Rogue River area.” This original dairy herd formed the basis for stock, which quickly populated the area and gained the settlers’ independence from the Hudson Bay Company.

Young died unexpectedly in 1841 without a known heir and with extensive land and cattle holdings and debt. His estate was in limbo, precipitating the need to form a provisional government that could administer his estate.

By 1850, there were close to 10,000 cows in the area, and by 1860, the number had risen to 53,000, forming the basis of a burgeoning industry, which exported butter, and later cheese, along with lumber and furs to San Francisco and the Yukon Territory. By 1900, there were 122,000 head.

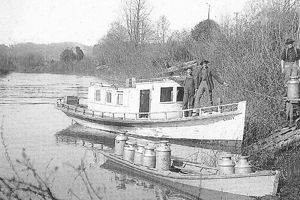

The 1890s saw a rise in the dairy factory system in Coos and Tillamook counties. Supplied by dairies along the fertile banks of the Coquille River, four buttermaking factories opened in Coos County. Milk was transported by sternwheel steamboats which would traverse the river before roads.

In Tillamook County, the first cheese factory was opened in 1894, followed by a second in 1895. The factories produced 50,000 pounds of cheese in the second year. Aided by technical expertise of Peter McIntosh, a Canadian from Ontario, the cheeses from Tillamook County quickly gained renown and a premium price at market. By 1903, 20 Tillamook factories were producing two million pounds of cheese a year.

In 1901, Professor F.L. Kent of Oregon Agricultural College embarked on a survey of all Oregon dairies west of the Cascades. He found 72 dairy plants in the state. From this initial survey, Kent realized the need to form a group that would improve the quality of butter in the state.

In 1910, the Oregon Buttermakers Assoication, a precursor of Oregon Dairy Industries was formed to improve quality of butter, which suffered from rancidity in early operations, limiting its value as an export to booming cities throughout the region.

Educational seminars were held through OBA and County Extension agents to inform agricultural and production practices, setting the stage for future expansion later in the century.

Oregon Cheese Festival

Say “cheese” and mean it at this year’s Oregon Cheese Festival at Rogue Creamery in Central Point on March 19.

Thousands of visitors will sample cow, sheep and goat cheese from Oregon creameries, including Fraga Farm, Juniper Grove Farm, Pholia Farm, Tumalo Farms, Tillamook County Creamery, Willamette Valley Cheese Co., Fern’s Edge Dairy, Rivers Edge Chèvre, Ancient Heritage Dairy, Fairview Farm Goat Dairy, Goldin Artisan Goat Cheese, Briar Rose Creamery, Mossy Oak Creamery, Rogue Creamery and more.

Other culinary artisans include Lillie Belle Farms, Dagoba Organic Chocolate, Gary West Meats, Rising Sun Farms, Applegate Valley Artisan Breads, Butte Creek Mill, Pennington Farms, Slagle Creek Vineyards, Paschal Winery, Madrone Mountain Vineyard, EdenVale Winery, Valley View Winery, Agate Ridge Vineyard, Daisy Creek Vineyard, Wandering Aengus Ciderworks, Deux Chats Bakery, Dry Soda, Cascade Peak Spirits and Rogue Ales.

To begin the festival, a multi-course meal introducing guests to participating artisans will be held at the historic Ashland Springs Hotel in Ashland, March 18. Prepared by the hotel’s executive chefs, David Georgeson and Kate Cyr, the dinner’s proceeds will benefit the Oregon Cheese Guild.

The Oregon Cheese Festival will be open to the public March 19 from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. at Rogue Creamery, 311 N. Front St., Central Point.

Tickets are $15 and include tastings and demonstrations; a $5 wine tasting fee includes a wine glass. Tickets to the dinner are $85 and available by calling 866-396-4704. For more information, visit www.roguecreamery.com.